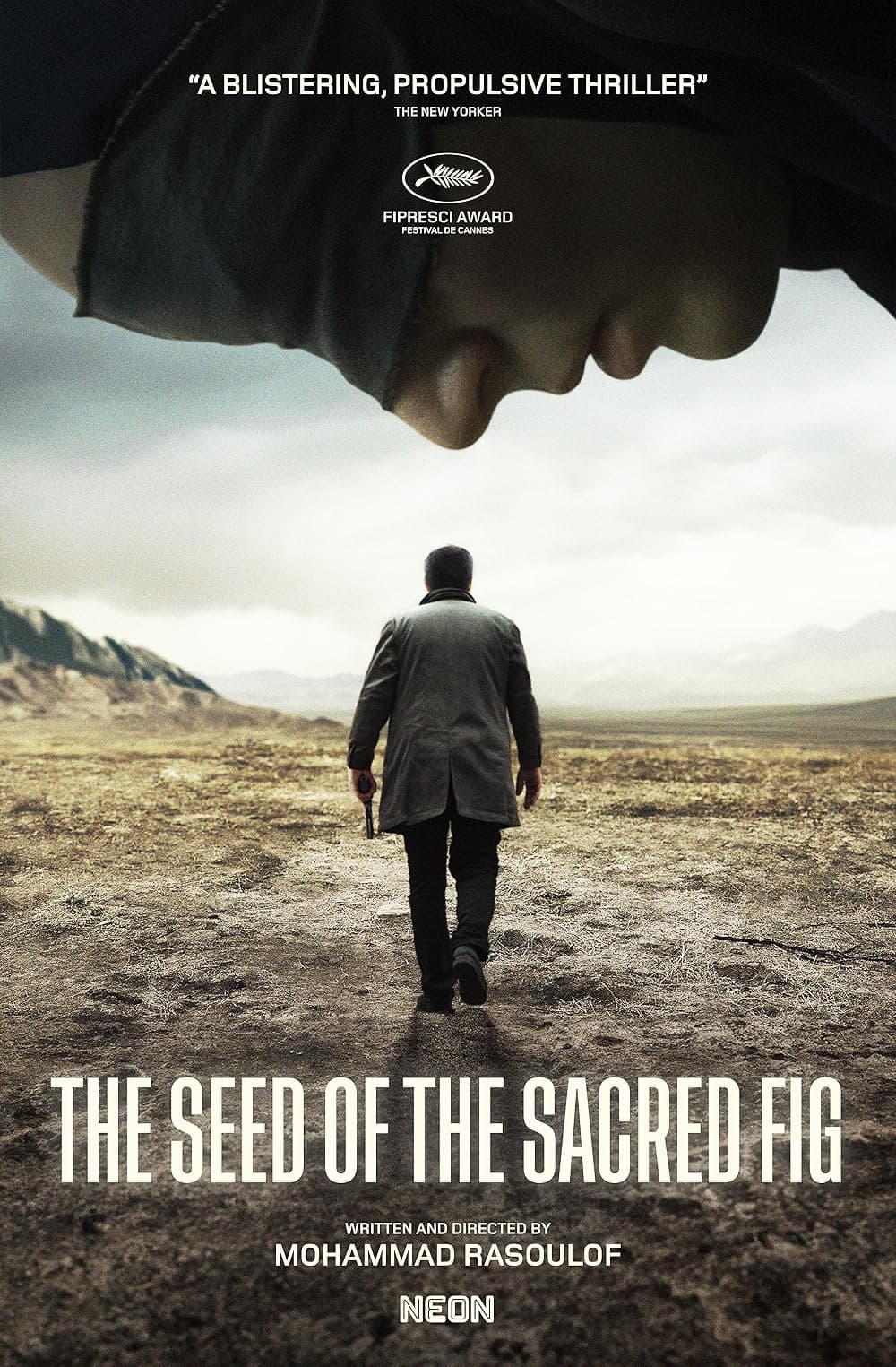

The Seed of the Sacred Fig

2024

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Shot clandestinely in Tehran, edited in secret, and triumphantly presented at the Cannes Film Festival just days after its director Mohammad Rasoulof's daring escape on foot from Iran to avoid a prison sentence, this film is one of those rare works in which art and life merge so powerfully and indissolubly that they transcend film criticism. It is a psychological thriller of almost unbearable tension, a family drama that turns into a devastating political allegory, and a work whose historical importance is matched only by its immense artistic value.

The premise is almost classically simple. Amid the turmoil of a Tehran shaken by the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests, Iman, an investigative judge at the Revolutionary Court, is promoted. With his promotion, he also receives a gun. But in a moment of chaos, the weapon disappears. This event is the spark that ignites a fire. Iman, a man of the regime whose identity is based on control and the exercise of power, sinks into an abyss of paranoia. The enemy is no longer just in the streets, but could be within his own walls. Suspecting his two young daughters, who openly sympathize with the protesters, and his wife, caught between loyalty to her husband and love for her daughters, he imposes increasingly strict rules, turning their apartment into a prison and his family into a courtroom. Family ties are put to the test as society outside and inside the home collapse.

The film follows in the footsteps of great Iranian cinema, but represents a crucial evolution. The influence of its founding fathers, particularly Abbas Kiarostami, is perceptible in the sobriety of style and attention to human dynamics. But while Kiarostami's cinema often used allegory and metaphysical allegory to ask universal questions with an almost poetic approach, Rasoulof's, like that of his contemporary Asghar Farhadi, is more direct, more tense, more rooted in social conflict. The Fig Tree takes the structure of a family drama that implodes because of a secret, typical of Farhadi's masterpieces such as A Separation, but charges it with an explicit and incandescent political significance. It is no longer just the crisis of the Iranian bourgeoisie, it is the crisis of an entire nation, the struggle between a dying patriarchy and a youth that is no longer afraid.

The social implications of the film in light of the current socio-political situation in Iran are its beating heart. The film is the first major fictional account to depict and draw on the energy of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, which emerged after the death of Mahsa Amini in 2022. In an act of extraordinary courage, Rasoulof includes real videos of the protests, filmed on cell phones and shared on social media, in the film. These images, seen by Iman's daughters on their phones, are not mere background. They are an intrusion of reality into fiction, a document bearing witness to the brutality of the repression and the courage of the protesters. The conflict between the father and his daughters thus becomes a conflict between two worldviews, between two ways of accessing the truth. Iman represents the state, which holds a monopoly on the official narrative, a narrative of order and stability. His daughters represent the decentralized and viral counter-narrative of the internet, a stream of images that exposes the lies of power. The problem of freedom of expression and stifled culture is not a theme, it is the very substance of the film.

If one looks for an oblique but profound parallel, the structure of the film evokes in an almost disturbing way that of The Crucible, Arthur Miller's famous play. As in Salem in 1692, a witch hunt is unleashed in Rasoulof's Tehran, but this time it is confined to an apartment. Iman, like Miller's Judge Danforth, is a man convinced of his own righteousness who, in the name of defending a moral order, unleashes an inquisition based on suspicion and paranoia. His daughters, implicitly accused of treason, are forced to defend themselves in a summary trial in which the accuser and judge are their own father. The atmosphere becomes suffocating, logic is perverted, and the search for truth is replaced by the demand for a confession, the only way to restore the paternal/state authority that has been called into question.

The title itself, The Seed of the Sacred Fig, is a powerful metaphor. During the film, one of the characters explains that sacred figs grow parasitically, their seeds sprouting on other trees, slowly enveloping them with their roots until they suffocate and take their place. This image can be interpreted in many ways: is it the regime suffocating society? Or, in a more hopeful reading, is it the seed of rebellion, planted by the new generation, which is slowly growing until it suffocates the old tree of patriarchal power? Rasoulof leaves the question open, but his film is an act of faith in this second possibility. It is a work of impeccable tension, beautifully acted, which manages to be at once a political thriller, a family drama, and a historical document of paramount importance. This film is living proof that cinema can sometimes be the only weapon left to tell the truth in the face of tyranny.

Shot clandestinely in Tehran, edited in secret, and triumphantly brought to the Cannes Film Festival a few days after its director Mohammad Rasoulof's daring escape on foot from Iran to avoid a prison sentence, this film is one of those rare works in which art and life merge so powerfully and indissolubly that they transcend film criticism. It is a psychological thriller of almost unbearable tension, a family drama that turns into a devastating political allegory, and a work whose historical importance is matched only by its immense artistic value.

The premise is almost classically simple. Amid the turmoil of a Tehran shaken by the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests, Iman, an investigative judge at the Revolutionary Court, is promoted. With it, he also gets a gun. But in a moment of chaos, the weapon disappears. This event is the spark that ignites a fire. Iman, a man of the regime whose identity is based on control and the exercise of power, sinks into an abyss of paranoia. The enemy is no longer just on the streets, but could be within his own walls. Suspecting his two young daughters, who openly sympathize with the protesters, and his wife, caught between loyalty to her husband and love for her daughters, he imposes increasingly strict rules, turning their apartment into a prison and his family into a courtroom. Family ties are put to the test as society outside and inside the home collapse.

The film follows in the footsteps of great Iranian cinema, but represents a crucial evolution. The influence of its founding fathers, particularly Abbas Kiarostami, is evident in its sober style and attention to human dynamics. But while Kiarostami's cinema often used allegory and metaphysical allegory to pose universal questions with an almost poetic approach, Rasoulof's, like that of his contemporary Asghar Farhadi, is more direct, more tense, more rooted in social conflict. The Fig Tree takes the structure of a family drama that implodes because of a secret, typical of Farhadi's masterpieces such as A Separation, but charges it with an explicit and incandescent political significance. It is no longer just the crisis of the Iranian bourgeoisie, it is the crisis of an entire nation, the struggle between a dying patriarchy and a youth that is no longer afraid.

The social implications of the film in light of the current socio-political situation in Iran are its beating heart. The film is the first major fictional account to depict and draw on the energy of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, which emerged after the death of Mahsa Amini in 2022. In an act of extraordinary courage, Rasoulof includes real videos of the protests, filmed on cell phones and shared on social media, in the film. These images, seen by Iman's daughters on their phones, are not mere background. They are an intrusion of reality into fiction, a document that bears witness to the brutality of the repression and the courage of the protesters. The conflict between the father and his daughters thus becomes a conflict between two worldviews, between two ways of accessing the truth. Iman represents the state, which holds a monopoly on the official narrative, a narrative of order and stability. His daughters represent the decentralized and viral counter-narrative of the internet, a stream of images that exposes the lies of power. The problem of freedom of expression and stifled culture is not a theme, it is the very substance of the film.

If one seeks an oblique but profound parallel, the structure of the film evokes, in an almost disturbing way, that of Arthur Miller's famous play The Crucible. As in Salem in 1692, a witch hunt is unleashed in Rasoulof's Tehran, but this time it is confined to an apartment. Iman, like Miller's Judge Danforth, is a man convinced of his own righteousness who, in the name of defending a moral order, unleashes an inquisition based on suspicion and paranoia. His daughters, implicitly accused of treason, are forced to defend themselves in a summary trial in which the accuser and judge are their own father. The atmosphere becomes suffocating, logic is perverted, and the search for truth is replaced by the demand for a confession, the only way to restore the paternal/state authority that has been called into question.

The title itself, The Seed of the Sacred Fig, is a powerful metaphor. During the film, one of the characters explains that sacred figs grow parasitically, their seeds sprouting on other trees, slowly enveloping them with their roots until they suffocate and take their place. This image can be interpreted in many ways: is it the regime suffocating society? Or, in a more hopeful reading, is it the seed of rebellion, planted by the new generation, slowly growing until it suffocates the old tree of patriarchal power? Rasoulof leaves the question open, but his film is an act of faith in this second possibility. It is a work of impeccable tension, beautifully acted, which manages to be at once a political thriller, a family drama, and a historical document of paramount importance. This film is living proof that cinema can sometimes be the only weapon left to tell the truth in the face of tyranny.

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...