The Trial

1962

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

An irresistible journey through one of the most brilliant novels of our time, one that Orson Welles, with his unmistakable visionary audacity, transforms into a cinematic hallucination of rare power. It is not merely an adaptation, but a reinvention that delves into the very soul of the Kafkaesque text, extracting not only its plot but its deepest emotional and philosophical resonance.

Welles grapples with the Kafkaesque archetype of the “mystifying surreal” and weaves a personal vision where Kafka's unfathomable bureaucracy, with its tentacular ramifications and perverse logic, is replaced, or rather, amplified by the suffocating alienation of a burgeoning new industrial civilization, a post-war society in which the individual is crushed by anonymous and relentless systems. His camera does not merely observe, but penetrates the existential anguish of a world where guilt precedes action and innocence is not an absolution, but a further condemnation to incomprehension. It is a work that speaks not only of totalitarianism, but of the muted psychological violence exerted by modern power structures, be they state, economic, or social.

A superb Anthony Perkins as K, a minor clerk torn apart by the grip of an obscure and elusive administration. Perkins, fresh from the iconic success of Psycho, brings to the screen a nervous vulnerability and a repressed neurosis that perfectly align with the archetype of the common man overwhelmed by the absurd. His K is not a tragic hero, but a recalcitrant victim, a modern Sisyphus condemned to push a boulder of uncertainty and paranoia, his dignity slowly crumbling under the weight of a faceless accusation. His performance is a tour de force of bewilderment and impotent rebellion, an unforgettable portrait of human fragility in the face of the inscrutable.

The man is summoned for a trial, but despite his immense efforts, he will neither be judged nor learn the reasons for the summons, a spiral of frustration that Welles makes palpable.

Filmed in a claustrophobic black and white that admirably renders the Kafkaesque atmospheres, the film is a masterpiece of expressionist aesthetics. Great work by cinematographer Edmond Richard who assists Welles in perfect synergy, transforming spaces into visual traps and shadows into menacing presences. The masterful use of deep focus, a direct legacy of Citizen Kane, allows Welles to orchestrate labyrinthine sets where every element is in focus, contributing to a sense of oppression and inevitable fate. The environments themselves – from the infinite staircases disappearing into darkness, to the gigantic and stark offices of the Gare d'Orsay, which becomes a monument to suffocating bureaucracy – become characters in their own right, embodying the omnipresent and disorienting nature of the "Tribunal." The black and white is not a limitation, but a bold stylistic choice that accentuates contrasts, immersing the viewer in a graphic nightmare where light struggles in vain against the darkness that envelops K.

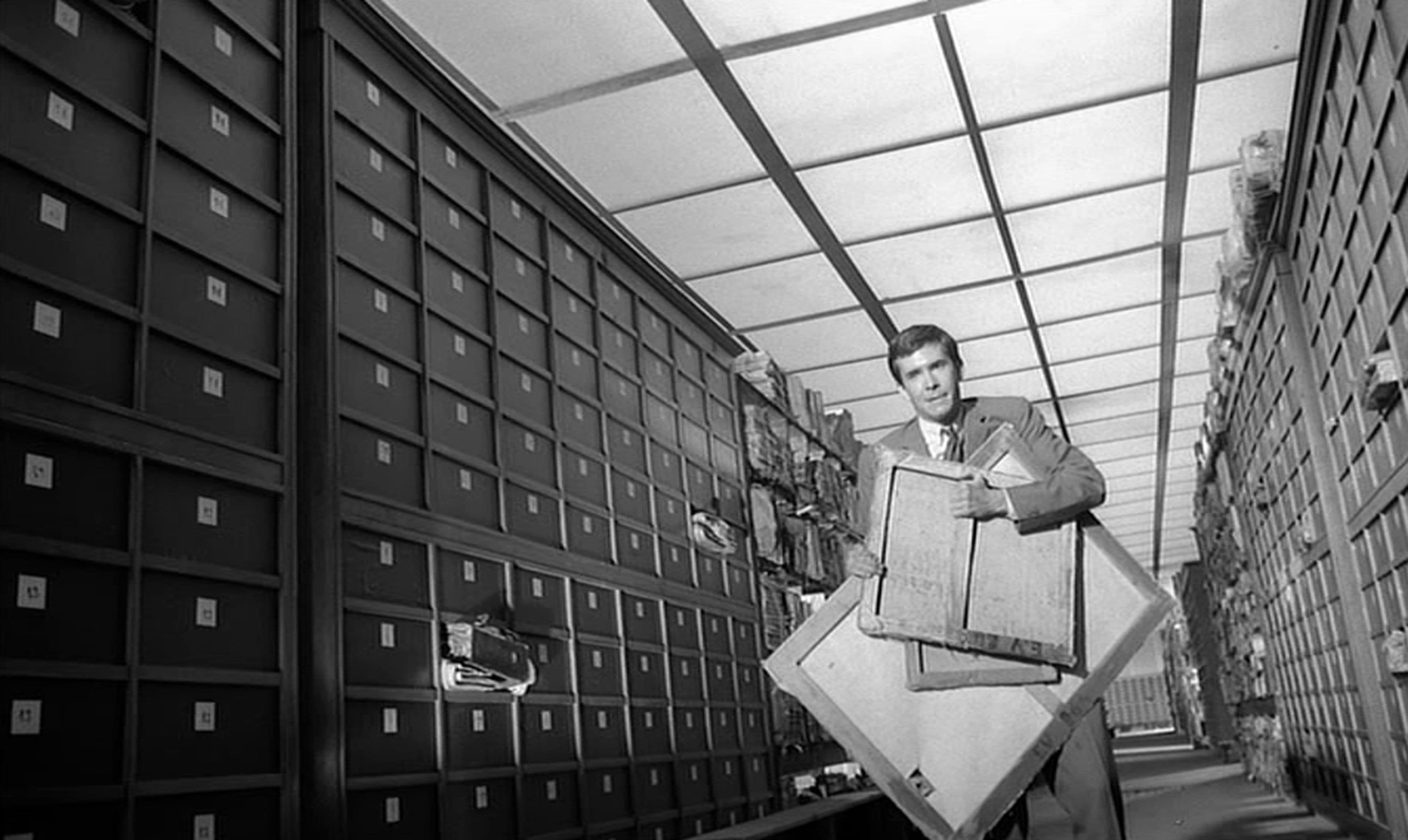

Memorable in this regard is the roving wide-angle shot with which Welles introduces us to K's dehumanizing workplace, the teeming anthill where a man is nullified with cold, scientific perfection. It is a sequence that evokes the dehumanization of the assembly line, an echo of Fritz Lang's dystopian visions in Metropolis or Charlie Chaplin's labor satires in Modern Times, but with a more subtle and intellectual vein of horror. Also long-lasting in memory are certain sequences, such as the scene where the two police officials serve K with the summons for his court appearance. Here, the man's bewilderment is palpable, amplified by the gratuitous bullying he endures from the two, by their bureaucratic arrogance which embodies the most insidious face of power: that which is exercised without justification, in mere routine. His flurry of hypotheses as to why he was summoned is a rational man's desperate attempt to find meaning in a universe that has deprived him of all logic, projecting his own anxieties and neuroses onto the system's indifference. Every shot is calibrated to convey K's growing paranoia, his total sense of isolation, the world shrinking around him like a cage. The reverberating echo of voices, distorted figures, the constant sensation of being watched, all contribute to building an atmosphere of impending threat and unreality.

Ultimately, the artistic union between Welles and Kafka proves remarkably insightful: in cinema, only the director of Kane has truly managed to fully transpose the ultimate meaning of Kafka's work, its most intimate grammar that makes this author a cornerstone of twentieth-century literature. Welles, with his predilection for solitary characters who clash with structures larger than themselves (one only needs to think of Charles Foster Kane himself or Quinlan in Touch of Evil), was the ideal interpreter to grasp K's existential solitude and the unfathomable nature of his battle. His cinema, composed of moral and psychological chiaroscuro, imposing architectures, and penetrating gazes, proved to be the perfect language to translate Kafka's labyrinthine prose and metaphysical anguish into images. Welles's "The Trial" is not just a film, but an immersive experience in paranoia and the absurd, a disturbing warning about the fragility of individual freedom in the face of a system that judges without explaining, and condemns without ever revealing its face. A timeless work, which continues to resonate powerfully in the complexities of our present.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...