Deliverance

1972

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

From a novel by James Dickey emerges a compelling and narratively well-crafted work that draws inspiration from the journey of four friends who decide to spend a weekend on a lake fishing and camping. An apparent ode to adventurous masculinity, to a confrontation with wild and purifying nature, instead reveals itself to be a relentless descent into hell, a raw allegory of the fragility of human civilization. James Dickey, not only the author of the electrifying novel of the same name, but also the remarkably perceptive screenwriter, intuits the cinematic power of his visceral prose, creating a perfect collision between literature and the seventh art. His novel, acclaimed for its psychological density and its exploration of the dark side of the psyche, finds in the film its most brutal and stark visual counterpart.

Their quiet vacation will transform into an ordeal of death and suffering thanks to some local thugs who attack them after they kill one of them while defending against an attempted assault. What begins as a recreational outing, an escape from urban captivity, is fiercely transformed into an odyssey of terror and degradation. The violence that erupts is not urban or sophisticated; it is primordial, unexpected, brutal in its simplicity, a direct confrontation with man's wildest nature, awakened in the heart of a forgotten America. The sequence of the attack on the river, far from being mere shock, imprints itself on memory as a chilling warning about the fragility of civilization and the thin line that separates "civilized" man from the beast.

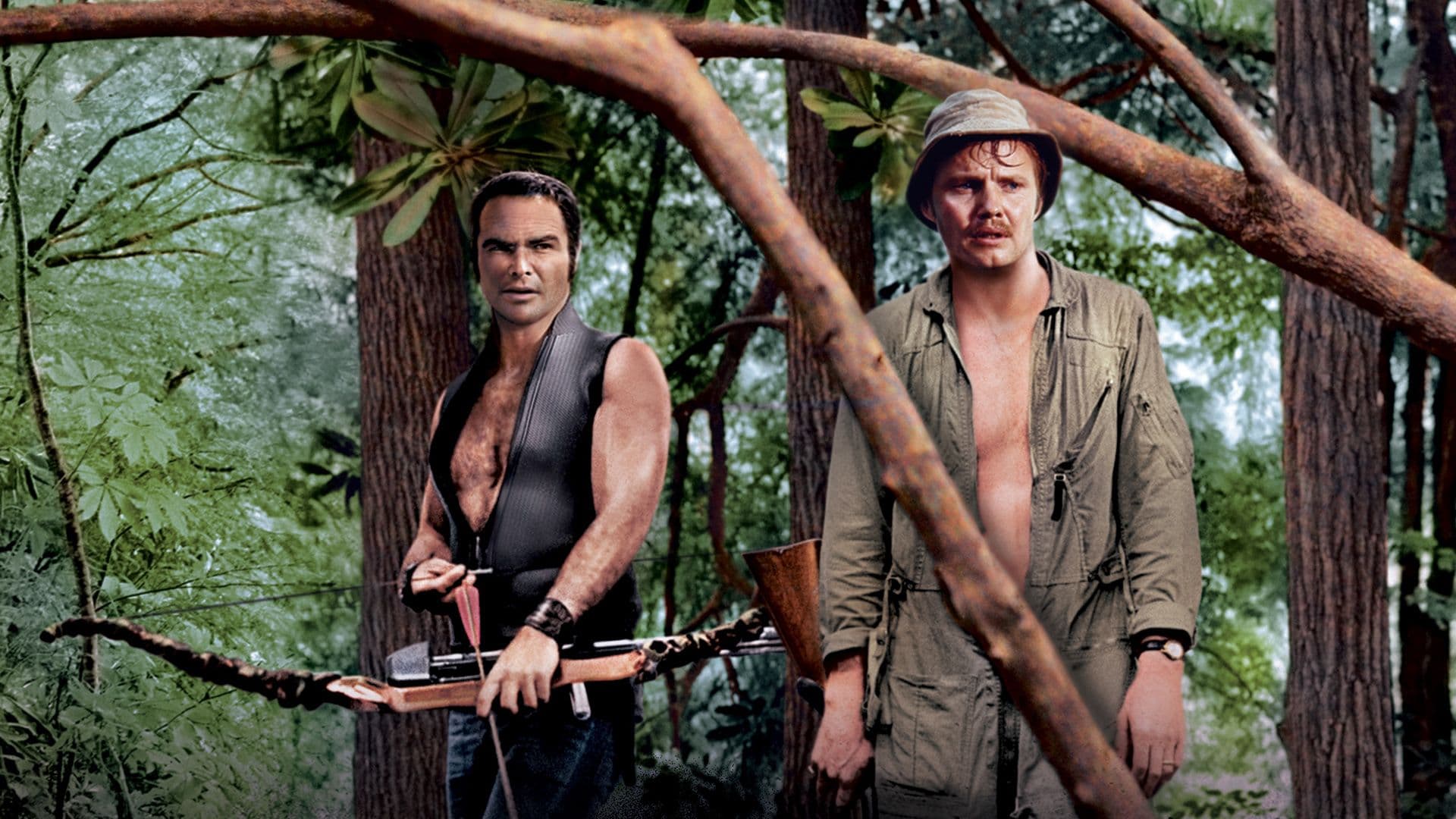

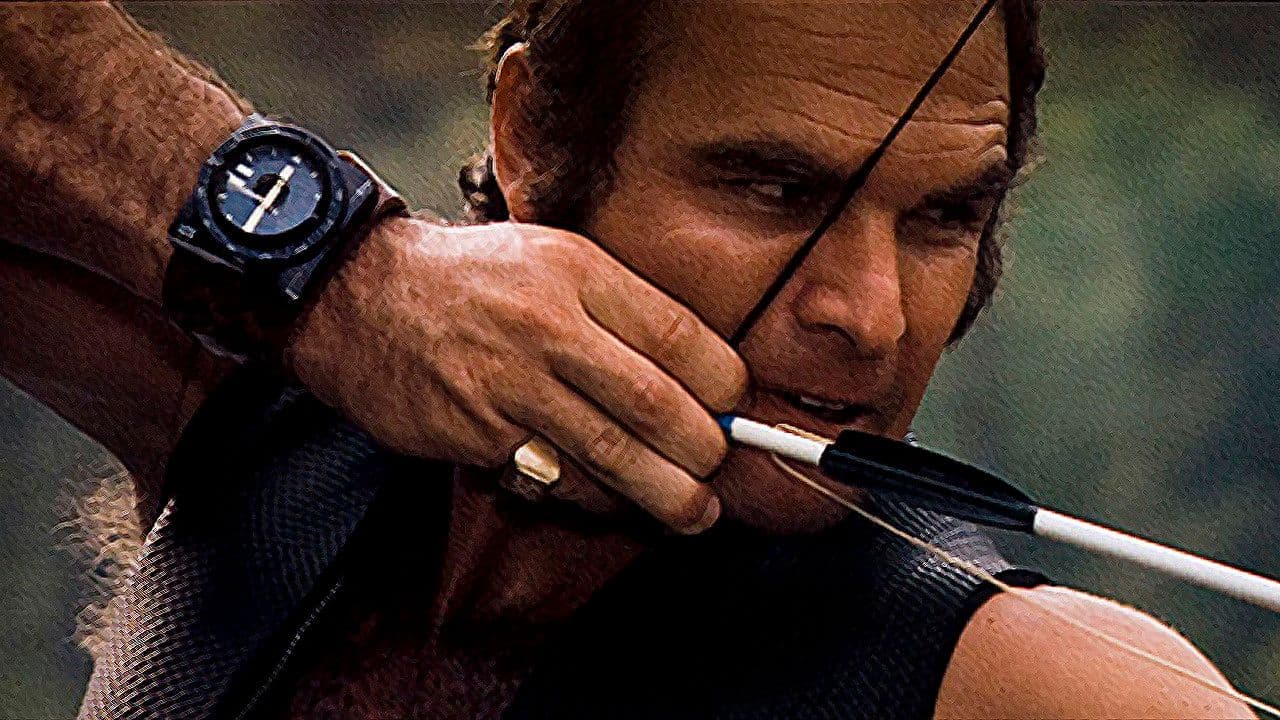

A great Burt Reynolds and an equally great John Boorman directing, truly remarkable in perfectly rendering the atmosphere of growing unease and alienation that the story takes on as the plot unfolds. Boorman does not merely direct; he carves out a sensory and psychological experience. His direction is a tour de force of unease, transforming the lush Appalachian landscape from a picturesque backdrop into a menacing character, a primordial entity that swallows and reflects the cruelty of men. His mastery in pacing the tension, in using deafening silence and the sounds of nature to amplify the sense of isolation, is palpable in every frame. Reynolds, in the role of Lewis Medlock, the stoic and almost Darwinian leader, departs from his sex symbol image to embody a tough yet vulnerable masculinity, forced to confront the limits of his presumed superiority. Alongside him, a remarkably sensitive Jon Voight as Ed, the common man forced to confront the unthinkable; an unforgettable Ned Beatty in his heart-wrenching vulnerability, and a Ronny Cox embodying lost innocence. Theirs is a quartet that explores the nuances of fear, guilt, and the instinct for survival, dissecting the very idea of masculinity and what it means to be "men" in the face of chaos. The film stands as a testament to 1970s cinema's ability to confront the dark side of the human psyche and American society without filters, an era when New Hollywood was not afraid to challenge conventions and explore the cracks in the American dream.

One memorable scene above all: the Banjo-Guitar duet between a local boy with Down syndrome and Drew, the musician of the group. The two study each other from a distance as they strum the strings of their instruments, then the melody becomes increasingly defined and faster, culminating in a country virtuosity. It is not just a musical interlude of ineffable beauty, but a brief, fragile bridge of human connection, a pure dialogue beyond words and cultural differences. In that contagious virtuosity, so vibrant it became an iconic record hit, an instant of almost utopian harmony is condensed, before the dissonance of violence shatters any possible understanding, leaving behind only desolation and the memory of a lost opportunity for mutual comprehension. It is the calm before the storm, ephemeral beauty before bestiality.

A final regret for the original title "Deliverance," sadly changed by the Italian distributor to a title perhaps suitable for a bargain-bin horror film. But the greatest betrayal, one that perhaps more than any other distorts the thematic depth of the work, lies precisely in this choice. The generic, B-movie horror label trivializes the unsettling ambiguity and philosophical resonance of the original title, "Deliverance." The latter is not a mere stylistic choice; it is the keystone of the entire film. "Deliverance" can mean salvation, liberation, but also the provision of something, or even the act of "giving birth" to an experience. The protagonists are "freed" from the fragile veneer of civilization, "delivered" into a primordial experience of terror and survival, but also "saved" (or perhaps condemned) by an encounter that forces them to confront their own capacity for brutality. It is the "delivery" to an inescapable destiny, the "liberation" of one's deepest fears, and the "salvation" (in a perverse sense) that comes from transcending human limits. The original title invites reflection on the nature of violence, the fragility of social order, and regression to an almost animal state, themes that resonate with the anxieties of a decade that saw Hollywood explore the dark side of America with unprecedented frankness. Deliverance fits perfectly into that vein of "survivor" or "nature run amok" cinema, but with a psychological depth that elevates it above mere genre, placing it alongside works like Peckinpah's Straw Dogs or Kubrick's dystopian vision of A Clockwork Orange, in the way all three interrogate the thin line between civilization and barbarism. The river is not just an obstacle, but a liquid boundary, a Limbo that separates the known world from the jungle of the psyche, where every man is alone with his most primal instincts. A journey that leaves scars not only on the body, but especially on the soul, delivering to the viewer an uncomfortable truth about the beast lurking within each of us, waiting only to be unleashed.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...