Viridiana

1961

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

After alluding to it and touching upon it in his previous films – from Él to the brilliant irreverence of Nazarín – Buñuel directly tackles the theme of mysticism, and specifically religion in relation to man seeking a path to redemption. This is not a spiritual quest in the canonical sense, but rather a ruthless inquiry into the persistence of faith in a corrupt world, the fragility of good intentions in the face of the harshness of human nature, and the intrinsic absurdity of claiming sanctity. Buñuel, the master of cinematic surrealism, once again dips his pen in the ink of irreverence and psychological analysis, revealing to us the hypocrisies and repressed urges that lurk beneath the surface of devotion.

Thus is born this work dense with morbid situations, with tensions towards sublime aims and sordid, utterly earthly effects. The film is a true essay in images on the dialectic between the ideal and the real, between angelic purity and atavistic bestiality. The story unfolds with an almost mathematical logic in its inexorable descent towards the cruelest antithesis.

The story is that of Viridiana, an orphan about to take her perpetual vows, who visits her wealthy uncle, Don Jaime, a man who has lived in a limbo of grief and solitude after the death of his wife. The man falls madly in love with her, a sick love, steeped in symbolic necrophilia – his obsession with the memory of his deceased wife is projected onto his niece, to the point of making her wear his wife's wedding dress. His is a passion that allows no half-measures, a perverse devotion that overturns the canons of pure love in a sordid and desperate attempt at possession. Faced with this wicked passion of his and an attempted sexual assault – only narrowly avoided due to a sudden paralysis of conscience, or perhaps, a supreme self-humiliation – the man hangs himself, leaving all his possessions to Viridiana. This traumatic event does not, at first, deter her from her spiritual path. On the contrary, it seems to strengthen in her a kind of mystical pride, the conviction that she must atone and redeem through a work of radical charity.

Thus begins the young woman's mystical journey, as she undertakes various acts of charity, welcoming a group of beggars and derelicts onto her estate, seeking to transform her uncle's legacy into a sanctuary of goodness and compassion. But these efforts of hers, animated by an almost childlike purity of intent, will inevitably backfire on her. The poor, far from being evangelical figures of humility and gratitude, prove to be a sampling of human vices: greed, laziness, lust, brutality. Buñuel mercilessly dismantles the idyll of Christian charity, showing its pitfalls and vanity when it clashes with the crude reality of a corrupt humanity, incapable of rising above its primary urges. This is the culmination of Buñuelian sarcasm, his bitter laugh in the face of the naivety of absolute good.

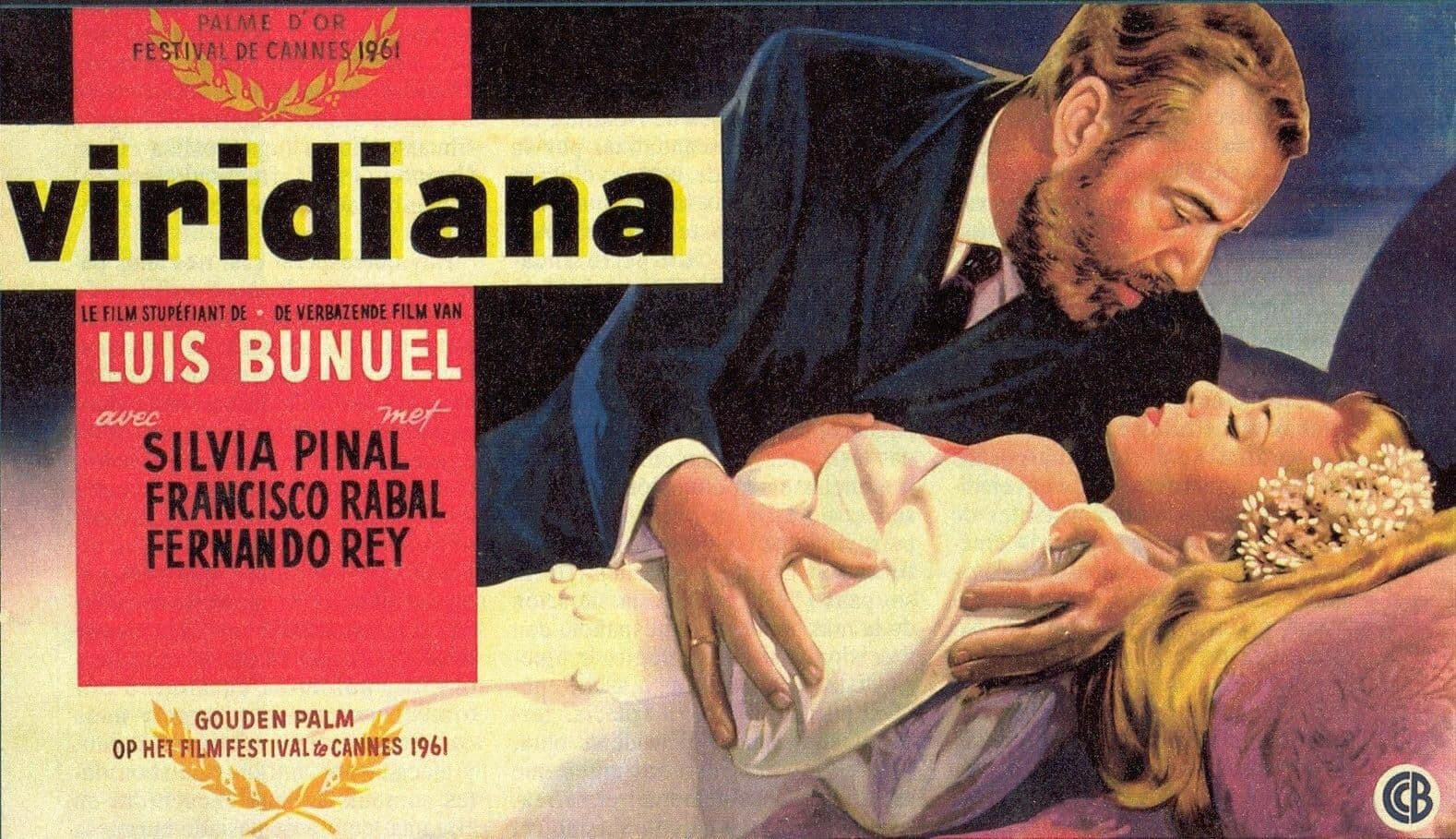

It is no surprise that a film of such caliber and audacity sparked much controversy, particularly with the Vatican, due to its alleged mockery of the Catholic religion. The tension culminated in a scene that became world-famous, and considered treacherously blasphemous by the ecclesiastical authorities of the time: the one depicting the beggars carousing in the villa, iconographically replicated from Leonardo da Vinci's celebrated painting, "The Last Supper." Buñuel does not limit himself to a mere visual reference; he subverts the sacred, he desecrates it with brutal lucidity. It is not simple parody that makes the scene so powerful, but rather its ability to reveal an uncomfortable truth: that spirituality, when not rooted in a deep and disillusioned understanding of human nature, risks collapsing under the weight of its own utopia. The beggars, transformed into apostles of a degraded humanity, not only profane the place but embody the vanity of every attempt at superficial redemption. The film was awarded the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1961, but Francoist Spain, initially proud of the international recognition of one of its exiled directors, was forced to withdraw the film from circulation, and its Director General for Cinema, José Muñoz Fontán, was dismissed for having endorsed its production. An epilogue that consecrated its aura as a cursed and prophetic film, a testament to Buñuel's rebellious genius.

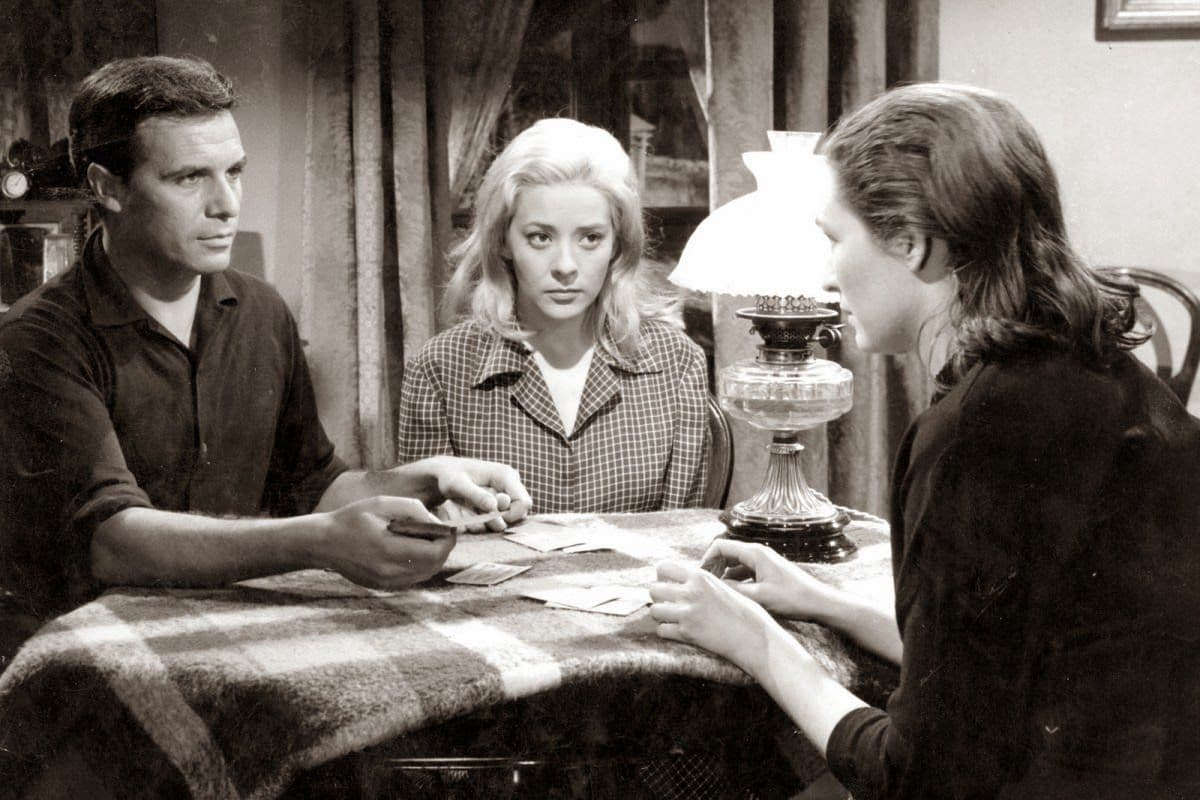

A film that carries within it the germ of lucid madness in the face of the purest sensuality, a sensuality that Viridiana attempts to suppress, but which forcefully resurfaces through her dynamics with Don Jaime first and then with her cousin Jorge. And it is precisely the final triangle, with Jorge, the pragmatic and disillusioned man, that suggests a way out of Viridiana's mystical impasse: no longer divine redemption or ineffective charity, but a disillusioned acceptance of life in its ambiguity. Her transformation, from aspiring saint to accomplice in a trivial card game, is not a moral fall, but perhaps a liberation from the prison of the ideal. At the same time, the film attempts to illustrate our fragility before God, or rather, before the idea we form of God and His will, an idea that often does not withstand the impact with the tangible reality of flesh and sin. Viridiana offers no answers, but poses uncomfortable questions, inviting the viewer to confront their own moralism, their own certainties, and the uncomfortable truth that the sacred and the profane are, in essence, two sides of the same, elusive, human coin. A masterpiece that continues to shine for its corrosive intelligence and timeless audacity.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...