West Side Story

1961

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Directors

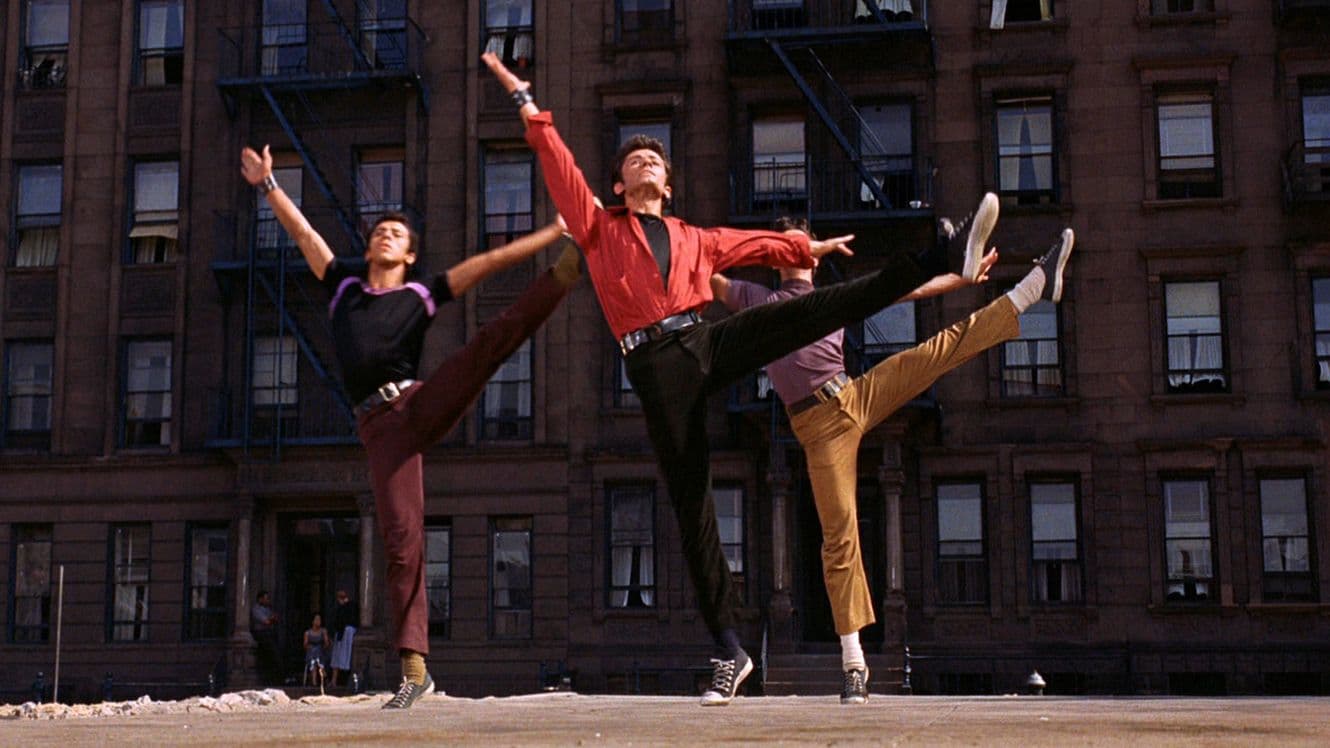

A film that redefined the canons of the musical, purifying it from the veneer of Hollywood saccharine and placing it in a metropolitan context where dance transforms into a struggle for survival, a desire to emerge, a bodily expressive canon understood as a primary, instinctive language. Whereas the classic musical had often settled for escapist narratives and glossy set designs, West Side Story erupts with the raw, vibrant energy of the streets, translating choreographic grace into a true dance of conflict, a primordial ballet in which every movement is a declaration of intent, a threat, a prayer, or a desperate yearning for freedom. It is physicality elevated to a symbol of social tension, the desire for affirmation, and the endemic violence pulsating beneath the surface of a seething metropolis.

Thanks to Leonard Bernstein's extraordinary compositional work and, above all, Jerome Robbins' exceptional choreographic genius, dance thus becomes pure narration, a new language with which to tell a story. No longer a mere interlude or virtuosic display, but an intrinsic dramatic element, the very engine of the plot. Robbins, hailing from classical ballet but with a profound sensibility for the vitality of modern dance and jazz, infused the choreographic sequences with such fluidity and power as to make them intelligible even in the absence of dialogue, expressing the anger of the Jets, the pride of the Sharks, and the melancholy of impossible loves with a mastery that transcends pure entertainment. The synergy between Bernstein's bold score, which blends jazz, Latin sounds, and classical counterpoints, and Robbins' taut and dynamic choreographies, creates a multisensory experience that envelops the viewer, unexpectedly pulling them into the streets of New York.

The narrative is a modern reinterpretation of Romeo and Juliet: two rival gangs, the Jets and the Sharks, confront each other in the slums for territorial dominance. But the New York of the film, depicted with almost documentary realism despite the musical's aesthetic, is not just the backdrop for a youthful feud; it is the crucible of deep social and racial tensions that were seething in post-war America. The Jets, children of "white" European immigrants, feel threatened by the massive arrival of Puerto Ricans (the Sharks), in a conflict of identity and belonging that goes far beyond mere street violence. Their clash is a micro-battle for control of a territory that symbolizes an illusory slice of the American dream, a microcosm of hatred and misunderstanding that mirrors the broader divisions of society. The choice of color, costumes, and disused urban settings, from the set design to outdoor shooting, contributes to creating an atmosphere of palpable tension, where the tragic beauty of the musical numbers stands out against the brutality of reality.

The love of Maria, sister of the Sharks' leader, for Tony, a member of the rival gang, will change the terms and fate of the dispute, revealing the inescapable tragedy that permeates the dynamics of hatred and prejudice. Their relationship is a fragile bridge thrown over the abyss of an ancestral feud, a lifeline that proves, in its purity and disarming naivety, insufficient to stop the spiral of violence. Maria and Tony's hope is a flickering light destined to be extinguished by the blind fury of sectarianism, making their sacrifice a bitter warning about the impossibility, at times, of escaping a fate written by society. The film does not grant easy happy endings, but ventures into territories of profound pessimism, suggesting that love, however powerful, can be overwhelmed by deeply rooted hatred.

Songs like “I Feel Pretty,” with its dreamy lightness contrasting with the surrounding reality, “One Hand, One Heart,” a hymn to the purity of a love destined for catastrophe, and “Something’s Coming,” charged with impatient premonition, instantly became hits, but their resonance goes far beyond radio success. They are sound architectures that define characters, propel the narrative, and serve as an emotional mirror, making every word of Stephen Sondheim and every note of Bernstein a fundamental piece of the cinematic experience. Even tracks like the satirical and vibrant “America,” which captures the ambivalences of the migratory experience, or the choral and fatalistic “Tonight,” which sets the stage for the decisive battle, demonstrate the soundtrack's incredible ability to be both a standalone work of art and a perfect integration of cinematic language.

Ten Oscars for a monumental hymn to the expressive power of the body, music, and images. West Side Story's triumphant victory at the Academy Awards, including statuettes for Best Picture and Best Director (awarded to Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins), was not just a recognition of technical and artistic excellence, but a consecration of a new paradigm in musical cinema. The film demonstrated that the musical could be dramatically powerful, socially relevant, and aesthetically audacious, paving the way for future productions that would not shy away from addressing darker themes or exploring new stylistic frontiers. The direction, often dynamic and innovative, with the use of wide camera movements that followed the dance and dramaturgy, imbues the film with an almost palpable energy, immortalizing the brutality and beauty of street life. West Side Story remains, decades later, a cornerstone not only of the musical genre but of cinema tout court, a timeless work on the destructive nature of prejudice and the ephemeral beauty of hope, which continues to resonate with the same intensity and urgency in the contemporary era.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...