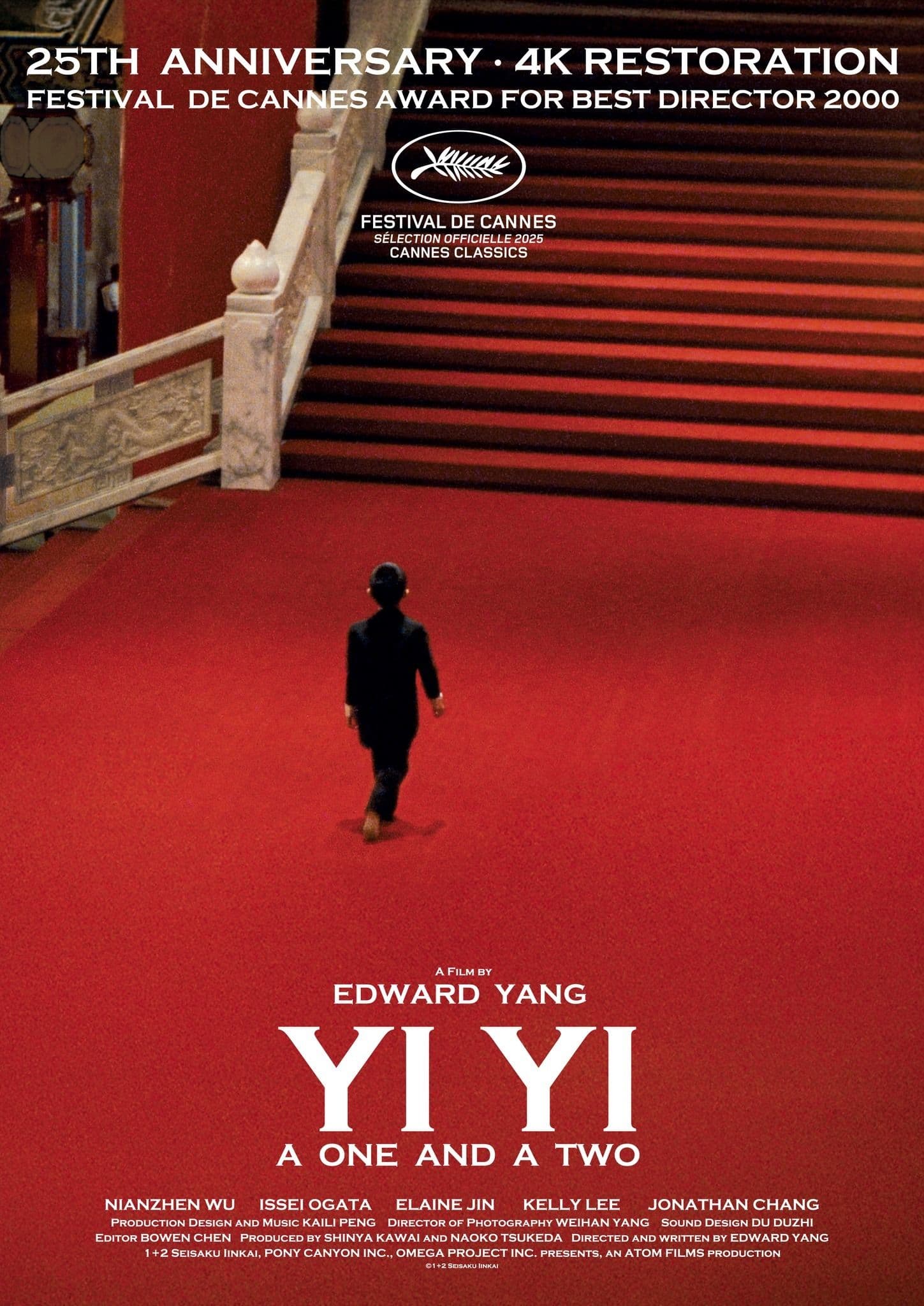

Yi Yi

2000

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

For three hours, the great Taiwanese master Edward Yang invites us into the life of the Jian family, an ordinary middle-class family in Taipei, and to observe, with boundless patience and humanity, their small joys, their silent despair, and their midlife crises. It is a work with the scope and depth of a great 19th-century novel, a choral fresco that rejects conventional drama to find the epic in the everyday. Watching Yi Yi is an immersive experience, an act of contemplation that leaves us not with answers, but with a deeper understanding of the complex, bittersweet, and wonderful fabric of life itself. For its wisdom and almost invisible perfection, it is a pillar of world cinema and an essential addition to the Movie Canon.

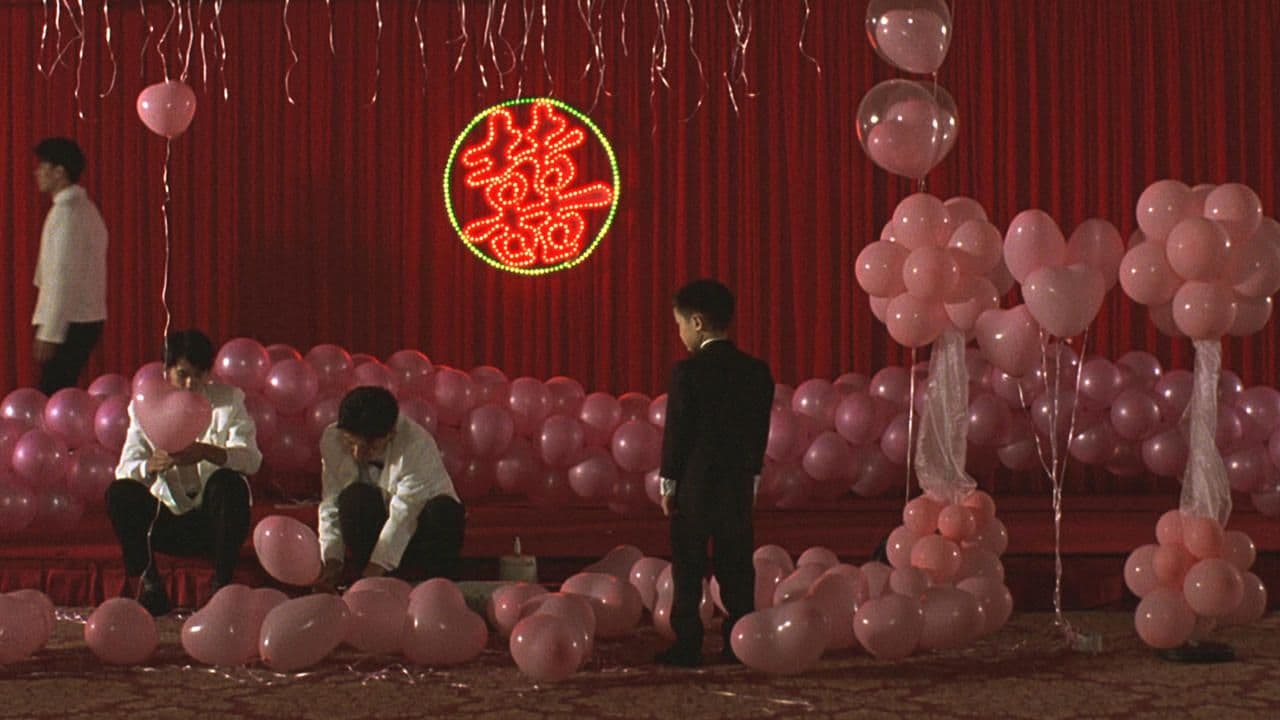

The film, whose title literally translates as “one one,” suggesting both individuality and succession, opens with a wedding and closes with a funeral, the two great rituals that mark the cycle of existence. In between, Yang orchestrates a symphony of parallel lives. It all begins, in fact, at a boisterous wedding. It is here that the family's grandmother has a stroke and ends up in a coma, an event that forces each member of the family to speak to her motionless body, turning it into a sort of silent confessional. It is also here that the father, NJ, a dissatisfied computer engineer, accidentally meets his first great love from his youth, Sherry, reopening a wound that has never completely healed. From this prologue, the stories of the three main members of the family unfold, living their lives in a kind of gentle and melancholic shared solitude.

NJ hates his job and, prompted by Sherry's return, begins to reexamine the regrets of his life, particularly his decision to leave her suddenly and without any real reason. His is not just a midlife crisis, but a philosophical inquiry into the nature of time and possibility. He asks himself, and us: if we could go back, would we make the same choices? His temporary escape to Japan on business becomes a pretext to see Sherry again, an attempt to relive the past to understand if a different life would have been possible. Is he idealizing the past to escape his unhappy present? Sure, but Yang doesn't judge him. He observes his wanderings through the streets of Tokyo and sterile hotel rooms with a mixture of empathy and melancholic lucidity.

Meanwhile, we follow his children. Teenager Ting-Ting feels guilty about her grandmother's stroke and, at the same time, experiences her first confusing and painful love triangle. Her story is a smaller-scale echo of her father's: she too experiences passion, betrayal, and regret for the first time. And then there is the most memorable and philosophically dense character in the film, the youngest son, Yang-Yang. Bullied at school and constantly teased for being “different,” Yang-Yang approaches the world with a serious, almost scientific curiosity. His decision to learn to swim on his own is a metaphor for survival, of course, but his real tool of investigation is a camera.

In this choral approach and patient aesthetic, Edward Yang reveals himself as the greatest modern heir to Japanese master Yasujirō Ozu. As in an Ozu film, the camera is often static, the shots are composed with an almost architectural rigor, and the drama unfolds in domestic spaces, during meals, in seemingly banal conversations. But while Ozu's cinema was pervaded by a gentle resignation to the end of a traditional era, Yang's is immersed in the alienation of a globalized modernity. The Taipei of Yi Yi is a city of glass and steel, of impersonal offices and reflections. His shots, which often trap characters behind windows or show them as reflections on shiny surfaces, evoke the cold urban melancholy of Michelangelo Antonioni. Yang is the perfect bridge between Ozu's classical humanism and Antonioni's analysis of modern alienation.

The meta-cinematic heart of the film, and its most brilliant insight, lies in Yang-Yang's passion for photography. At one point, he starts taking pictures of the backs of people's heads. When his father asks him why, the child replies with disarming logic: "You can't see it. So I help you see it.“ This simple sentence encapsulates the entire philosophy of Edward Yang's cinema, and perhaps of cinema itself. The director, like Yang-Yang, is the one who shows us the parts of our lives that are invisible to us, the truths that are too close to be perceived. He shows us the ”back of the head" of our existence. Yang-Yang, with his innocence, becomes the miniature director of the film, the one who has understood that art is a way to double life, to see it from a perspective that would otherwise be closed to us.

The film culminates with the grandmother's funeral. The cycle is complete. NJ has encountered his past again and realized that there is no going back, but that perhaps that is not a bad thing. In his final speech, he whispers that since Ting-Ting was born, it is as if he has lived his childhood again, and that perhaps life is not so short if you can live it several times, through others. And then, the final scene. Yang-Yang reads a letter to his deceased grandmother. He tells her the things he has learned, his discoveries, and concludes by saying, “I feel old too.” At that moment, the child has attained a profound wisdom, an awareness of the cycle of life, of birth and death. Yi Yi is a work of boundless richness and complexity, a film that teaches us that every life, even the most ordinary, contains a whole universe of joys and sorrows worth telling.

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...