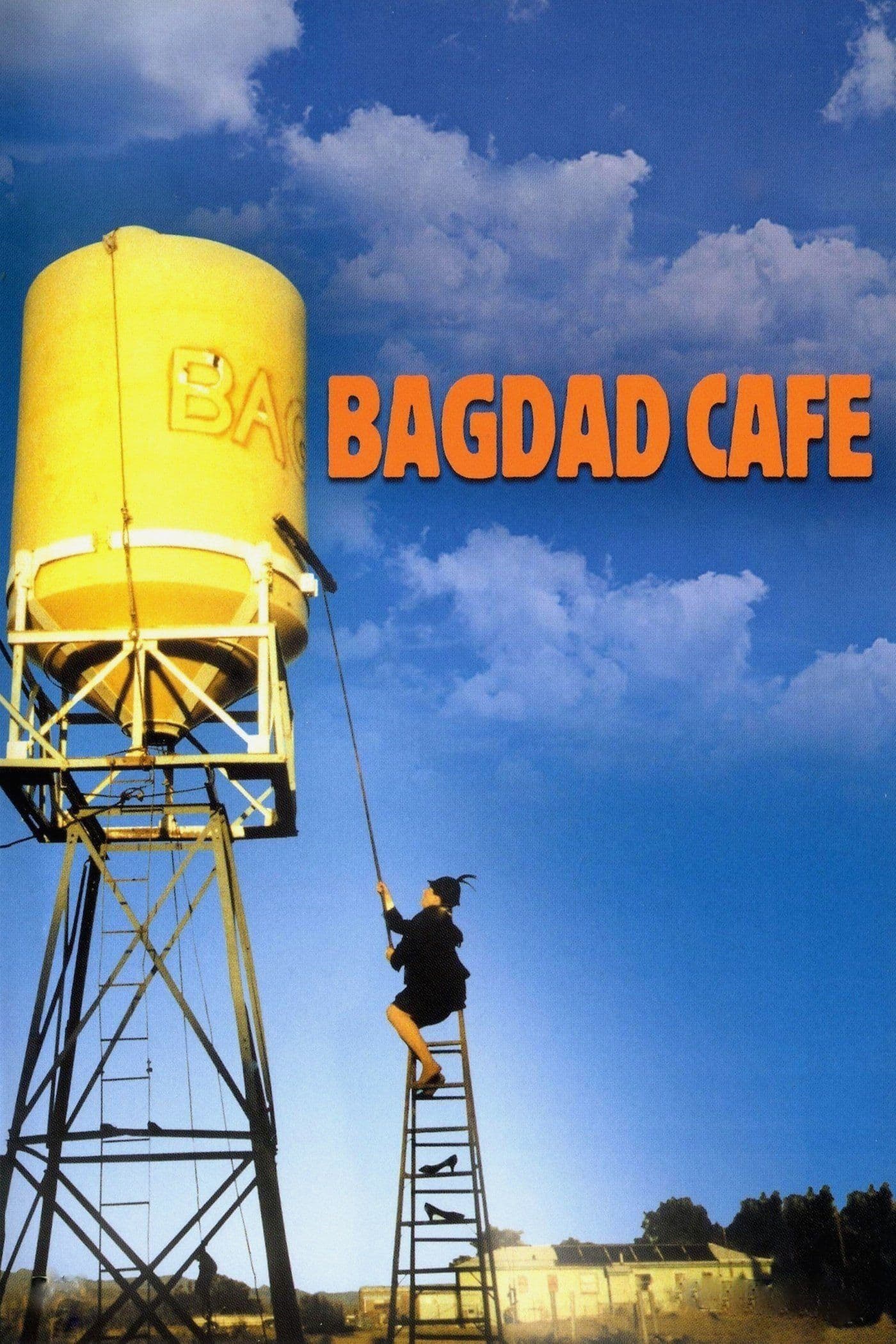

Bagdad Cafe

1987

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Percy Adlon presents us with this small yet great film where a handful of lives intersect in an utterly desolate motel in the Arizona desert, in the middle of nowhere. A non-place that, in Adlon's vision, transforms from a space of transit and abandonment into a crossroads of souls, a surreal oasis in the vast, relentless void. Bagdad Cafe is not just a motel; it's a true secular purgatory, a dusty limbo where social conventions and individual certainties melt away under the relentless Mojave sun, allowing humanity's barest and most vulnerable essence to emerge. Adlon, perhaps a less celebrated figure compared to the giants of New German Cinema like Wenders, Herzog, or Fassbinder, demonstrates a unique sensibility here, capable of distilling poetry and tenderness from the absurd and the marginal, a stylistic hallmark that makes him an ideal bridge between rigorous European introspection and visionary American eccentricity.

From this emerges a concert of grotesque personalities that fuels the narrative fire with delicacy and lightness. Not a gallery of freak shows to be viewed with detachment, but a kaleidoscope of unforgettable figures, each with their own wounds and unexpected resources. From the piano-obsessed boy to the enigmatic female patrons, to the cook who dreams of Italy, each character is a dissonant but essential note in a symphony of everyday madness. Adlon does not judge, but observes with an almost anthropological affection, allowing these "existences on the fringes" to reveal themselves in all their layered humanity, overcoming clichés with subtle humor and touching empathy. It's an approach that at times recalls Fellini's pietas for his life's circus performers, while maintaining a vein of typically German minimalism and quietude, which avoids hyperbole in favor of the intimacy of detail.

The narrative focuses on two female characters who will bring order to the chaos of men and things: Jasmin Münchgstettner, the German woman in Bavarian costume who arrives in that God-forsaken place after arguing with her husband, and Brenda, the owner who has to deal with a lazy husband and a son who only thinks about playing his piano. The encounter between Jasmin and Brenda is a genuine clash of worlds. On one side, the Teutonic order, Jasmin's contained eccentricity, her almost ritualistic meticulousness; on the other, Brenda's chaotic disorder, fierce irascibility, and deep-seated disillusionment. It is a cultural, but above all existential, collision that Adlon masterfully handles, avoiding easy caricatures to delve into the depths of their fragilities and unexpected complementarities.

The two women will slowly learn to know and appreciate each other. Their journey is a dance made of silences, gestures, small shared rituals – a cup of coffee, cleaning the premises, an oblique glance – which gradually erodes the wall of suspicion and resentment. Jasmin, with her unexpected reserve of wisdom and her propensity for everyday magic, begins to decipher Brenda's unspoken language, to perceive the weariness behind the anger, the vulnerability beneath the armor. This process of mutual discovery is never forced, but organic, a delicate blossoming that elevates their relationship to a universal metaphor for the possibility of overcoming linguistic and cultural barriers to form new, unexpected families.

Jasmin will make herself useful at the Motel, becoming, with her sober eccentricity, a point of reference for the guests and Brenda. Her figure, almost a transformative muse, brings a touch of enchantment and discipline to the desert of life. It's not just her meticulousness in cleaning, the order she instills in the rooms, or the unexpected quality of the coffee she prepares that changes the atmosphere; it's her very presence, quiet and magnetic, her ability to see beyond appearances and celebrate small joys. Her magic performances, initially clumsy and then increasingly hypnotic, are not mere tricks, but rituals that restore a sense of wonder and connection in an arid and disenchanted environment. Jasmin is the archetype of the stranger who, through her otherness, becomes a catalyst for a collective renaissance, bringing to mind figures like Pasolini's enigmatic visitor in Teorema, though with far more benevolent and constructive intentions.

Each story naturally comes to light, embedding itself within the others, forming a single coherent, multi-textual fresco. The film unfolds in a series of vignettes that intersect without hierarchy, where the individual's story enriches that of the collective. It is a narrative structure that rejects dramatic linearity in favor of a more meditative and choral progression, almost a visual stream of consciousness that unfolds at the slow pace of desert life. Adlon's skill lies in making us perceive the deep interconnectedness between these solitary souls, demonstrating that even in the most remote places, community can flourish through mutual acceptance and the tacit recognition of others' fragilities. A microcosm that reflects, on a reduced scale, the dynamics of a world searching for a sense of belonging.

Special mention for Jack Palance's performance as Rudi Cox, a moving, truly remarkable portrayal. Palance, an actor usually associated with villain or tough-guy roles, here reveals himself with disarming vulnerability, bringing to life a character of unexpected delicacy. Rudi Cox, the former Hollywood set painter who now portrays the motel's customers, is the artist and observer par excellence, whose sensitive vision captures people's authentic souls. His relationship with Jasmin, made of glances, silences, and mutual inspiration, is of an almost surreal tenderness, a bulwark against cynicism. Palance's performance is a lesson in subtlety and depth, confirming his acting genius and offering the audience one of the most unusual and touching portraits of his career, an icon of artistic and personal rebirth.

A film that reconciles us with humanity and its weaknesses, featuring a splendid soundtrack (let's remember Jevetta Steele's poignant "Calling You," also nominated for an Oscar). But the sonic impact of Bagdad Cafe extends far beyond the single track, iconic as it may be. Bob Telson's music, with its jazz, blues, and gospel accents, permeates every frame, serving as an emotional and narrative bridge. The melody of "Calling You" is not just a leitmotif; it's a genuine invocation, a melancholic yet hopeful lament that rises in the desert's silence, symbolizing the universal search for connection and belonging. The film is a modern fable about the resilience of the human soul, a hymn to the ability to find beauty and solidarity even in the most remote and forgotten corners of the world. It is a work that invites tolerance, curiosity towards others, and the rediscovery of magic in small things, leaving the viewer with a persistent feeling of warmth and optimism, an invitation to believe in the possibility of a miracle, even when the desert sand seems to swallow everything. Its resonance is universal, a gentle and necessary reminder of how love, art, and simple kindness can transform the most desolate of places into a blooming garden of humanity.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...