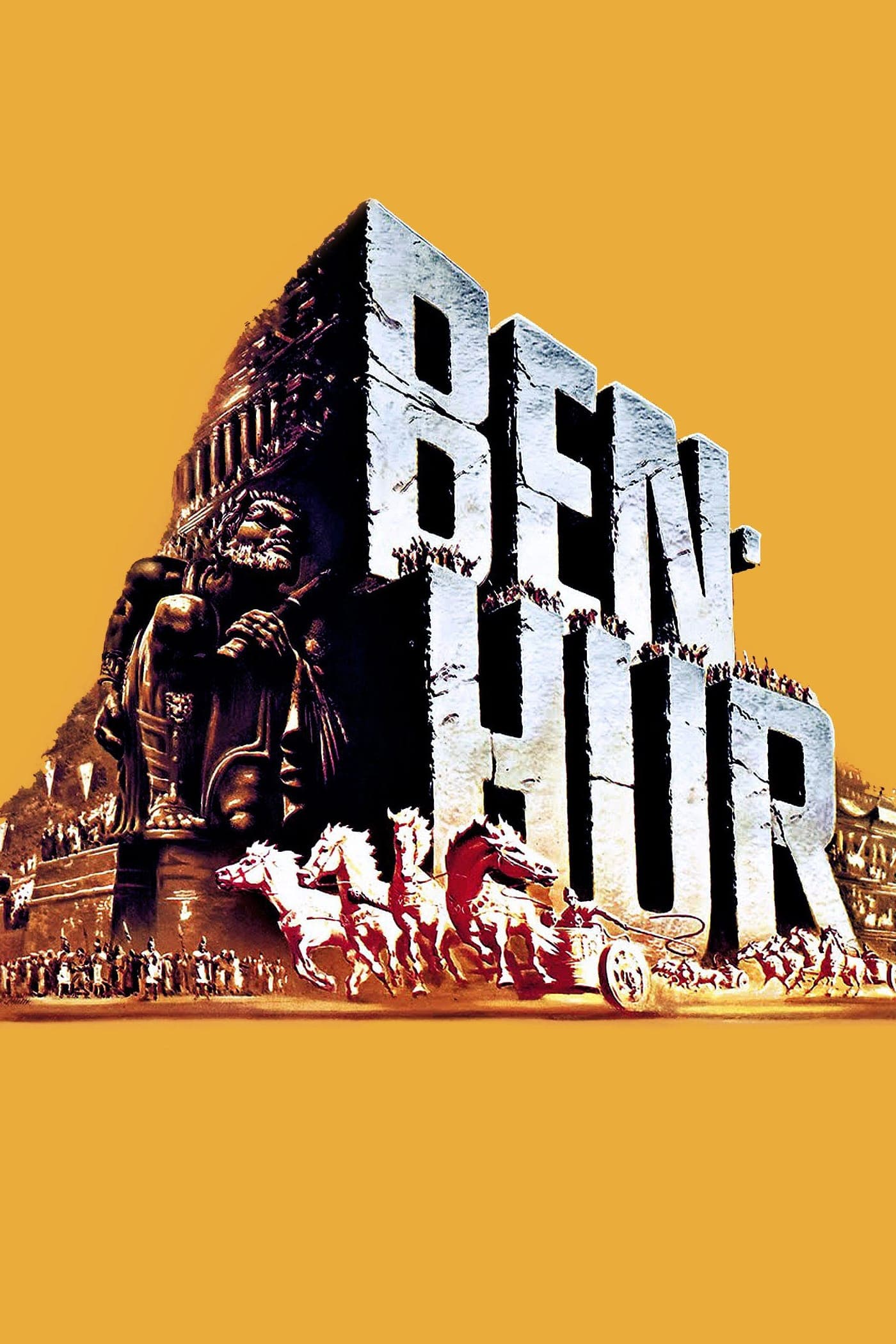

Ben-Hur

1959

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

The first great epic film in Hollywood history was born through the hands of an ambitious director like Wyler and a subtle dramaturgical work on Wallace's novel by Tunberg. William Wyler, a filmmaker with a refined touch, known for his meticulous attention to characters even in the grandest settings, as demonstrated in masterpieces such as The Best Years of Our Lives, faced the challenge not only of directing an undertaking of biblical proportions but also of instilling humanity and psychological depth into a genre that until then had often favored grandiloquence at the expense of profundity. Karl Tunberg's “subtle work” consisted of distilling Lew Wallace's verbose and overtly evangelical epic, purging it of didactic excesses to forge a screenplay that could speak to a universal audience, balancing the sacredness of the original text with the narrative and spectacular demands of the 20th-century big screen. It was an operation of extremely delicate balance, aimed at transforming a religious parable into a gripping human saga, strategically timed also in an era when Hollywood sought to counteract the rise of television with spectacles of unparalleled size and splendor.

With these simple yet effective ingredients, a truly titanic operation came to life, from which the film's three-and-a-half-hour running time reflects the scale of the production. We are talking about astronomical figures for the time: a budget of fifteen million dollars, employing tens of thousands of extras, reconstructing the Circus Maximus over an eighteen-acre area with breathtaking authenticity, and managing thousands of horses, chariots, and costumes. This was not merely a logistical feat, but an act of faith in cinematic art as a total immersive experience, capable of transporting the viewer back in time, into a world recreated with maniacal detail. The choice of widescreen format, often Cineama, was intrinsic to this vision, expanding the narrative horizon far beyond the confines of the small home screen.

The story is that of a noble Jewish prince, Ben Hur, unjustly accused by a childhood friend, now a Roman tribune and administrator of his region. The dynamic between Judah Ben-Hur and Messala is not a mere rivalry of circumstance, but an ideological and spiritual collision that resonates through the centuries. Messala, an embodiment of the pragmatic and often brutal efficiency of the Roman Empire, seduces with the promise of power and order, contrasting with the steadfast faith and millennial identity of the Jewish people that Ben-Hur represents. Their friendship, purest in youth, corrupts under the weight of irreconcilable duties and ideologies, making the final confrontation not just a matter of personal revenge, but the symbol of a conflict of civilizations, a struggle between oppression and freedom, between faith and cynicism.

Ben Hur is enslaved and begins his wanderings around the early Christian world (it is 29 A.D.) only to return, in a sort of Moebius strip, to his starting point, to achieve his revenge. This path is not a simple physical journey, but a profound spiritual odyssey. Slavery, the galleys, the encounter with Sheikh Ilderim, and the chariot races are stages of an inner transformation, a slow but inexorable detachment from the thirst for revenge to embrace a higher concept of justice and, ultimately, forgiveness. The year 29 A.D. is not a random detail; it places the story at a crucial moment in human history, the dawn of Christianity, allowing the figure of Christ to permeate the narrative with his subtle but omnipresent presence, offering a path to salvation not through earthly power, but through spiritual redemption.

Many words have been spent on this film, but one concept, above all, is worth circumscribing: the dimension of “epic” is redefined. Ben Hur is not limited to grandiose spectacle, though it remains an unsurpassed master of it; it elevates the genre to a new standard, combining the grandeur of its set design and crowd scenes with an intimate narrative and a deep psychological exploration of the characters. Where previous epics, such as Cecil B. DeMille's productions, often favored biblical didacticism and lavish staging, Ben Hur infused authentic emotional complexity and a character transformation arc that made it not only a visual experience but also an emotional journey. It established an archetype for future epic films, influencing works ranging from Lawrence of Arabia to Gladiator, demonstrating that the epic could be as intimate as it was monumental.

Ben Hur is, first and foremost, a gripping story that becomes a saga by reviewing the pivotal points of its time: the early evangelization of Christ, Roman political oppression, the decadence and corruption of Rome, and the nobility of spirit of the humblest strata of the population. The "early evangelization" is not presented explicitly or didactically, but manifests through the compassionate and mysterious presence of Christ, whose lesson of love and forgiveness contrasts with the brutal and vengeful logic of Rome. Roman oppression is not merely a plot element, but a character in itself, an omnipresent entity that shapes the destiny of conquered peoples, highlighting its ruthless efficiency and, at the same time, its intrinsic moral fragility. The decadence and corruption of Rome are delineated through the unrestrained opulence and cruelty of its representatives, a striking contrast with the dignity and unshakeable faith of the "humblest strata," who in the film often embody true nobility of spirit, a silent but unstoppable force. This intricate dialogue between macro-historical forces and individual micro-stories gives the film a specific weight that elevates it beyond mere entertainment.

A film that is, first and foremost, catharsis, purification, a detachment from the din of the modern world; then comes the spectacularization of the struggle, the exaltation of the hero, the titanic will that triumphs over all. Catharsis, in the Aristotelian sense, is the destination of this journey: purification from destructive passions, liberation through suffering and faith. The "detachment from the din of the modern world" is an invitation to rediscover universal narrative archetypes, the great questions about existence, justice, and destiny, which resonate in every era. The "spectacularization of the struggle," culminating in the unforgettable chariot race, is not only a technical virtuosity (and it remains astonishingly so today), but the emotional and symbolic climax of the film. It is a ballet of brute force, strategy, and pure will, in which Ben-Hur's personal revenge merges with his quest for redemption, becoming the ultimate expression of his "titanic will" to overcome adversity. The victory is not only physical but moral, a triumph of spirit over hatred. This masterpiece not only dominated the 1960 Academy Awards night with a record eleven statuettes but cemented its position in film history as a monument to classic epic and Hollywood's ability to create dreams on an unimaginable scale, a work that continues to resonate for its narrative power and eternal message.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...