Big Deal on Madonna Street

1958

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A work that, after more than 50 years, retains all its charm as a faithful cross-section of the underbelly of diverse humanity that somehow attempted to stay afloat and make ends meet. It is not just a portrait, but a living fresco of post-war Italy, a crossroads of miseries, shattered dreams, and a comical, almost involuntary resilience that translates into the art of making do. This "underbelly" is not the glorified one of the purest Neorealism, but a brilliant deviation, a "pink neorealism" that does not shy away from the harshness of life but mocks it with a bitter smile, almost as if to exorcise hunger and uncertainty with the lightness of laughter. Unemployment, endemic poverty, the mirage of well-being that always seems within reach yet never graspable, find here a representation that transcends mere documentalism to elevate itself to a universal human parable.

A masterful Monicelli sketches a handful of characters who seem sprung from a Boccaccio novella, yet bear the unmistakable marks of popular Rome, with its cadences, its tics, its naive cunning. His mastery is not limited to actor direction but extends to writing capable of imbuing dignity and moving pathos even into the most marginal or caricatural figures. This gallery of "accidental heroes" or, rather, "anti-heroes by necessity," is a tribute to Commedia dell'arte, but with a profoundly modern sensibility and a vein of melancholy that is the distinctive signature of Commedia all'italiana, of which the film is a cornerstone.

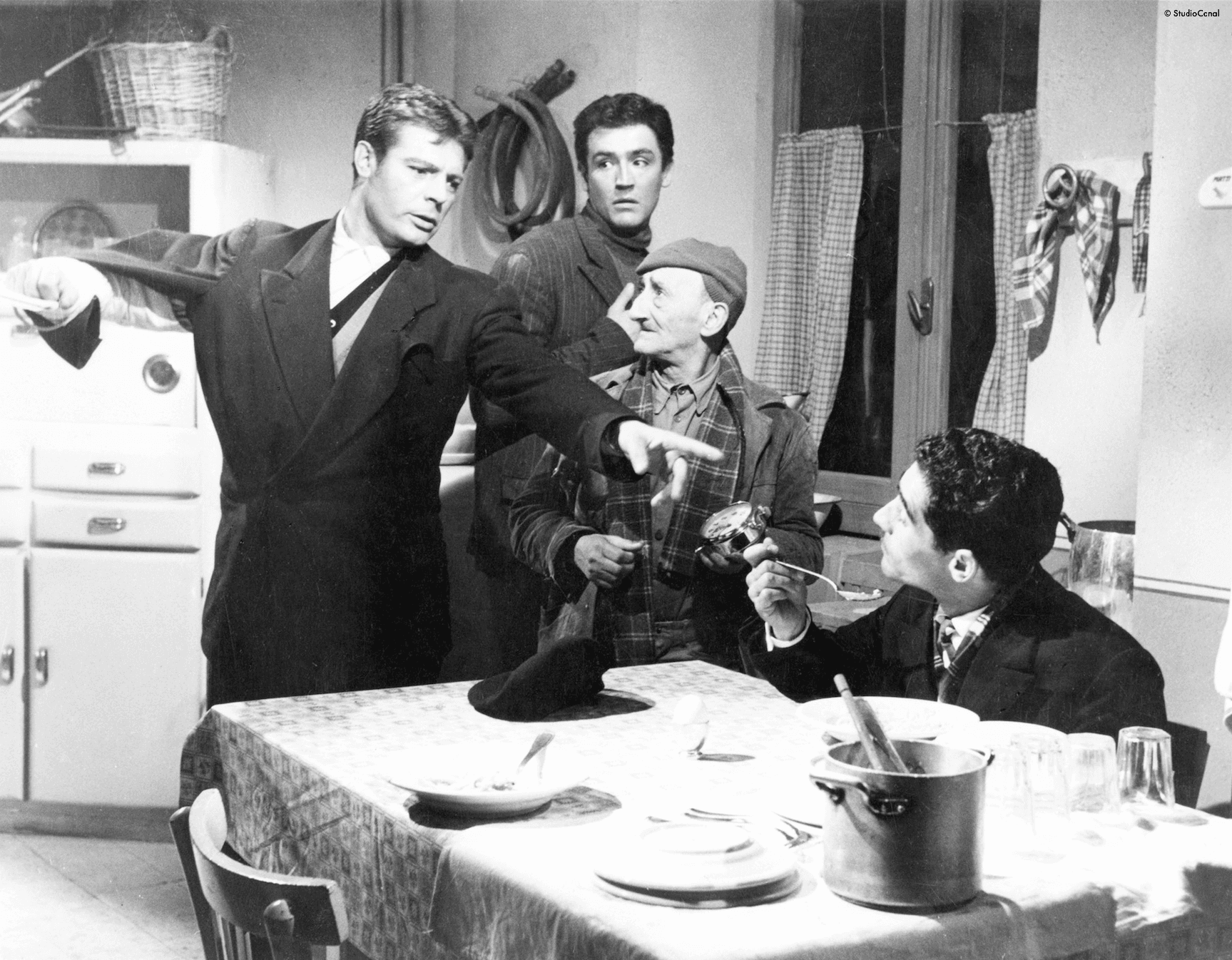

There is Peppe, the stammering boxer played by Gassman, an absolute revelation. Gassman, the actor with the noble bearing and impeccable diction, is here transformed into a grotesque and irresistibly comical mask, anticipating by years his own metamorphosis into Monicelli's Brancaleone. His stammering is not a mere comedic device but the symptom of a vulnerability, an inability to express himself fully in a world that does not understand him. There is Tiberio (Mastroianni) grappling with his family troubles, a tired and disillusioned common man, whose figure reflects the everyday life of many Italians, a prototype of the petit bourgeois who would become the hallmark of many of his future characters. And then there is the eccentric and unpredictable gang leader, Totò, of course, whose Capanelle, despite appearing for a limited time, leaves an indelible mark. Totò here is not the histrionic and overflowing prince of laughter, but a master of life on the verge of madness, an almost Shakespearean figure in his lunar and disillusioned wisdom, who carries Neapolitan comedy to new shores, demonstrating a subtle and moving acting ability. The ensemble, enriched by an unforgettable Carla Gravina, the vitality of Memmo Carotenuto, and the sly Carlo Pisacane (Capannelle), is a true polyphonic chorus of despair disguised as lightness.

Together they will work on the heist of a lifetime: robbing the Pawn Shop by breaking through a partition wall of an adjacent house. But the robbery, more than a daring criminal act, immediately reveals itself to be a tragicomic farce, a muddle orchestrated by desperate amateurs. The entire plan is a parodic subversion of sophisticated American "caper movies": here there are no brilliant minds or advanced technologies, but only a heap of unlucky and inept individuals, armed more with good intentions than skill. Their inexperience, their congenital bad luck, and their very humanity condemn them to failure even before they start, transforming the typical suspense of the genre into an irresistible chain of misunderstandings and disasters. The genius lies precisely in subverting expectations, in transforming the epic of crime into an ode to inefficiency and clumsiness.

A lesson in comedy infused into lived experience contaminated by haphazardness and folly. It is not slapstick comedy, but one that arises from the acute observation of social dynamics, from Monicelli's ability to grasp the absurd in the everyday and the pathetic in the farcical. It is a laugh that often chokes one's breath a little, because behind the buffoonery one always glimpses the harsh reality of survival.

Enjoyable, amusing, irreverent, tangible as a Verga novel, for its adherence to a raw realism and the celebration of society's "underdogs," "the vanquished," who here, unlike Verga's characters, do not succumb but cling to life tooth and nail, inventing new strategies of subsistence. It is roguish like a Folengo tale, for its ability to blend the sublime and the grotesque, cultured language and vernacular, in a cinematic "macaronic" that is pure genius. Its influence was so profound as to define an entire cinematographic genre: it is the Big Bang of Commedia all'italiana, which here finds its purest form and its unmistakable stylistic imprint, paving the way for decades of masterpieces that would laugh at human miseries without ever forgetting their intrinsic dignity.

Monicelli's greatness lies in creating shared emotion and pathos through an interweaving of everyday life scenes, simple gestures, dialogues that seem stolen from the street. There is nothing forced; every expression, every gaze, every pause contributes to building an authentic and vibrant portrait. His is a poetics of small things, a hymn to the resilience of the Italian people, to their ability to find a glimmer of joy even in the most desolate of conditions. This manifests exemplarily in the perfect scene where the gang, finding nothing to steal, settles for a plate of pasta, abruptly halting the tension and creating a temporary oasis of refreshment and peace. This sequence, apparently a simple diversion, is in reality the pulsating heart of the film, a manifesto of its philosophy. The act of sharing food, a primary symbol of nourishment and conviviality, becomes a secular rite of communion, almost a small last supper of hope. In that moment, physical hunger prevails over the craving for wealth, and the naive desire for a better life condenses into the archetypal gesture of nourishment. It is a powerful image, contrasting the futility of the failed robbery with the reassuring concreteness of survival, synthesizing the deepest soul of a cinema that knows how to be universal while remaining firmly rooted in its Italian specificity. It is here that failure transforms into a kind of moral victory, or at least a truce, a brief moment of harmony among losers, reminding us that true wealth, at times, resides simply in a warm meal and in company.

An indispensable touchstone of our cinema to contend with, a compass for understanding not just a genre but an entire nation, its fragilities and its irresistible vitality. "Big Deal on Madonna Street" is not just a film, but a foundational myth, a timeless classic that continues to speak to our deepest identity, a masterpiece that redefined the boundaries of comedy, elevating it to a tool of profound social and human analysis.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...