Blow-Up

1966

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

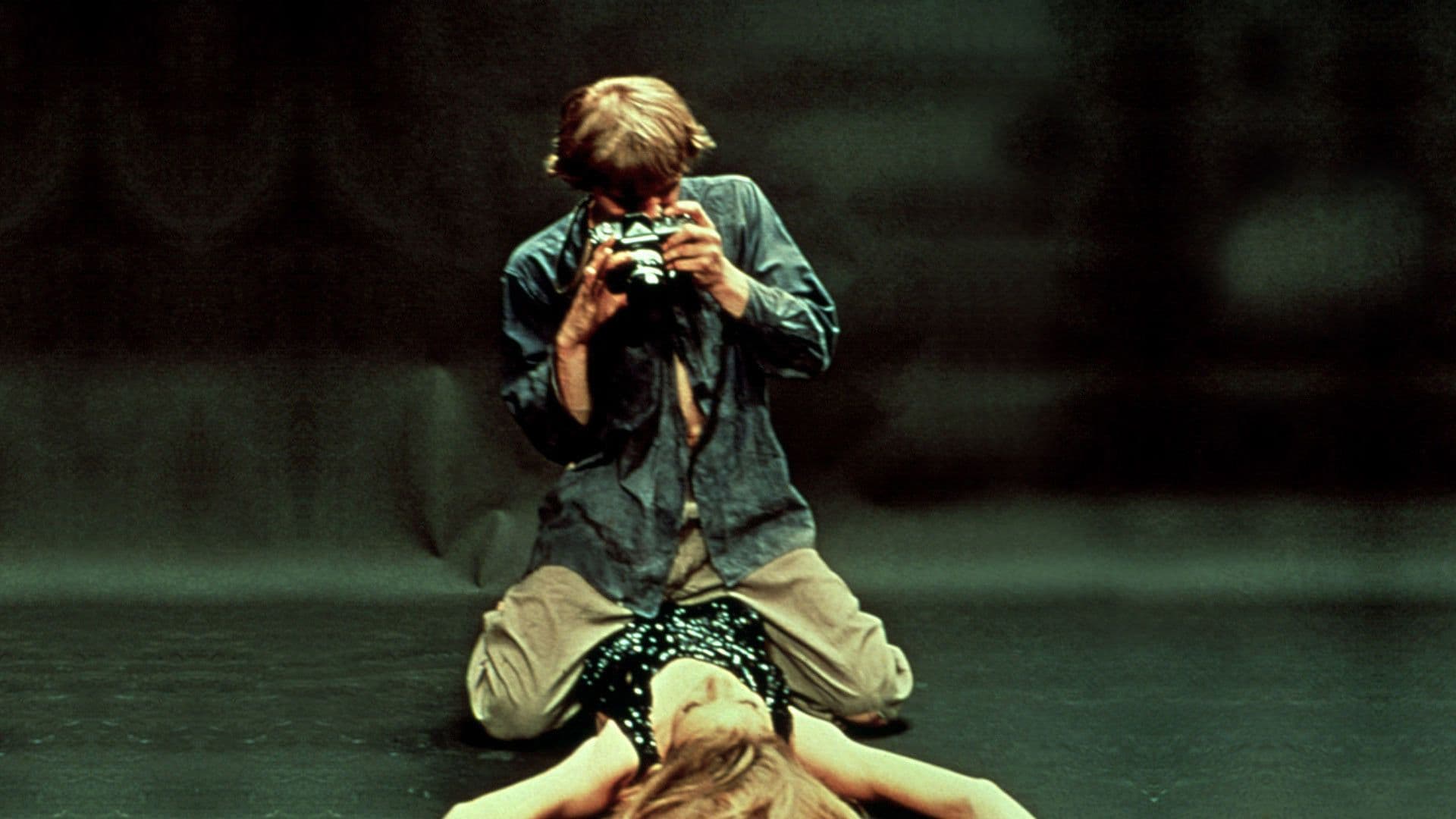

The detail comes to light in the darkroom… slowly. An almost alchemical process, where darkness and chemical solutions perform a magic that transcends the mere fixation of light, transforming it into revelation, or perhaps into deception.

And the photographer realizes that the photograph holds proof of a murder. An apparently innocuous frame, a snapshot of a London park, unveils itself under the magnifying lens like a contemporary hieroglyph, concealing violence and mystery within its nuances.

He will begin a personal investigation, taking that exposed plate as his starting point. It is not a simple police investigation; the echo of a noir quickly dissolves, giving way to a much more introspective and dizzying journey. Thomas, the protagonist, is not a detective but an artist, a demiurge of perception, which immediately makes his path a reflection on the very nature of image and truth.

Soon he will begin to doubt the very fabric of the Real, as if that photograph had opened a door to an unexplored zone where matter and dream are indistinguishable. The initial certainty of the "proof" corrodes under the weight of analysis, each enlargement, each graininess, adding not clarity but ambiguity, layering the unknown. It is the microscope pointed not at the event, but at perception itself. Reality, previously taken for granted, reveals itself as a fragile construct, permeable to optical and cognitive illusions, a canvas too thin to bear the weight of its own presumed objectivity. It is the classic epistemological dilemma that has tormented philosophers and artists, here translated into a burning and immediate visual form.

The story of Blow Up, set in a London in the midst of the beat revolution, unfolds from this casual occurrence. But "Swinging London" is not merely a backdrop; it is a character, a catalyst, a pulsating entity of energy and vacuous superficiality that Antonioni captures with almost ethnographic precision. Thomas, portrayed with hypnotic ambiguity by David Hemmings, is the perfect archetype of the disillusionment that permeates this effervescent metropolis: a successful fashion photographer, surrounded by ephemeral beauties (including a very young Jane Birkin and the legendary Veruschka), immersed in a vortex of hedonism and casual sex. His life, initially dominated by a detached cynicism and an incessant search for external stimuli, reflects the glossy glamour and intrinsic alienation of an era that celebrated formal freedom but suffered from a profound crisis of meaning. The vivid color, the psychedelic music of The Yardbirds, the aesthetic audacity of this pop London are not just style, but a metaphor for distraction, for the background noise that prevents one from grasping the underlying dissonance, the elusive truth.

The investigation Thomas will conduct will gradually transform from an anxiety for truth to permanent doubt, a continuous state of indeterminacy where the truth to be established is no longer whether a person was murdered but whether reality itself is an unmovable concept or if it has somehow been contaminated by the illusions of the mind. The film, loosely inspired by Julio Cortázar's short story "Las babas del diablo" – which also explores the ambiguities of photography and perception – elevates the mystery to an ontological level. The vanishing body, the missing gun, the absence of any tangible proof are not plot flaws, but radical narrative choices that reflect the central thesis: objective reality is a mirage, a collective illusion. Thomas, the man who captures and fixes images, finds himself ironically powerless in the face of its fluidity. It is the existential drama of contemporary man, lost in a labyrinth of signs without anchored meanings.

Paradigm-shifting in this sense is the delightful scene of the mime tennis match: Thomas is wandering in a public park when a group of young people dressed as mimes begin a tennis match without rackets or ball. The gesture, the pantomime, the acoustic sonification of nothingness, create a parallel reality, yet incredibly convincing. Thomas, initially amused and almost sarcastic, will, as the minutes pass, fall into the fiction, going to pick up an invisible ball and throwing it back to the players (but is it truly fiction, or is it reality stripped bare of all cognitive artifice?). This is the pulsating heart of the film, a scene that transcends mere allegory to become an experiment on perception. The sound of the invisible ball, the sound that Thomas hears and that we, the spectators, are induced to hear, is the final blow to our trust in reality. It is the moment when the veil of Maya is torn, and Thomas is no longer a detached observer but an active participant in the absurd. It is a cry of liberation and at the same time a lament for the loss of all points of reference, a sublime expression of the Theater of the Absurd transported to the big screen. His gesture of picking up the invisible ball is not a sign of madness, but of acceptance, a surrender to the ineluctable fluidity of existence.

Michelangelo Antonioni signs one of the most fascinating works of his filmography, his first feature film in English, a daring exploration of themes already present in his famous "trilogy of incommunicability" (L'Avventura, La Notte, L'Eclisse) but here amplified and contextualized within a vibrant and pop visual aesthetic. His style, characterized by long silences, shots that linger on faces and spaces, and an elliptical narration that favors the unsaid, perfectly aligns with the subject matter. Antonioni offers no answers, but poses questions, leaving the spectator in a state of perpetual questioning. His direction is not descriptive, but interrogative, pushing the camera not to reveal, but to interrogate the world.

A work in which the semiotic power of the image (symptomatic in this case that the protagonist is a photographer) emerges devastatingly, surpassing any dialectical attempt to achieve ultimate knowledge. Blow Up is not a film about a murder, but about the impossibility of knowing, about the elusiveness of the real, about the disillusionment of the human eye and the camera. The image, from a tool of revelation, becomes a metaphor for the very ambiguity of the human condition. A masterpiece that continues to question us, almost sixty years after its release, about the fragility of truth and the eternal interplay between what we see and what is.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...