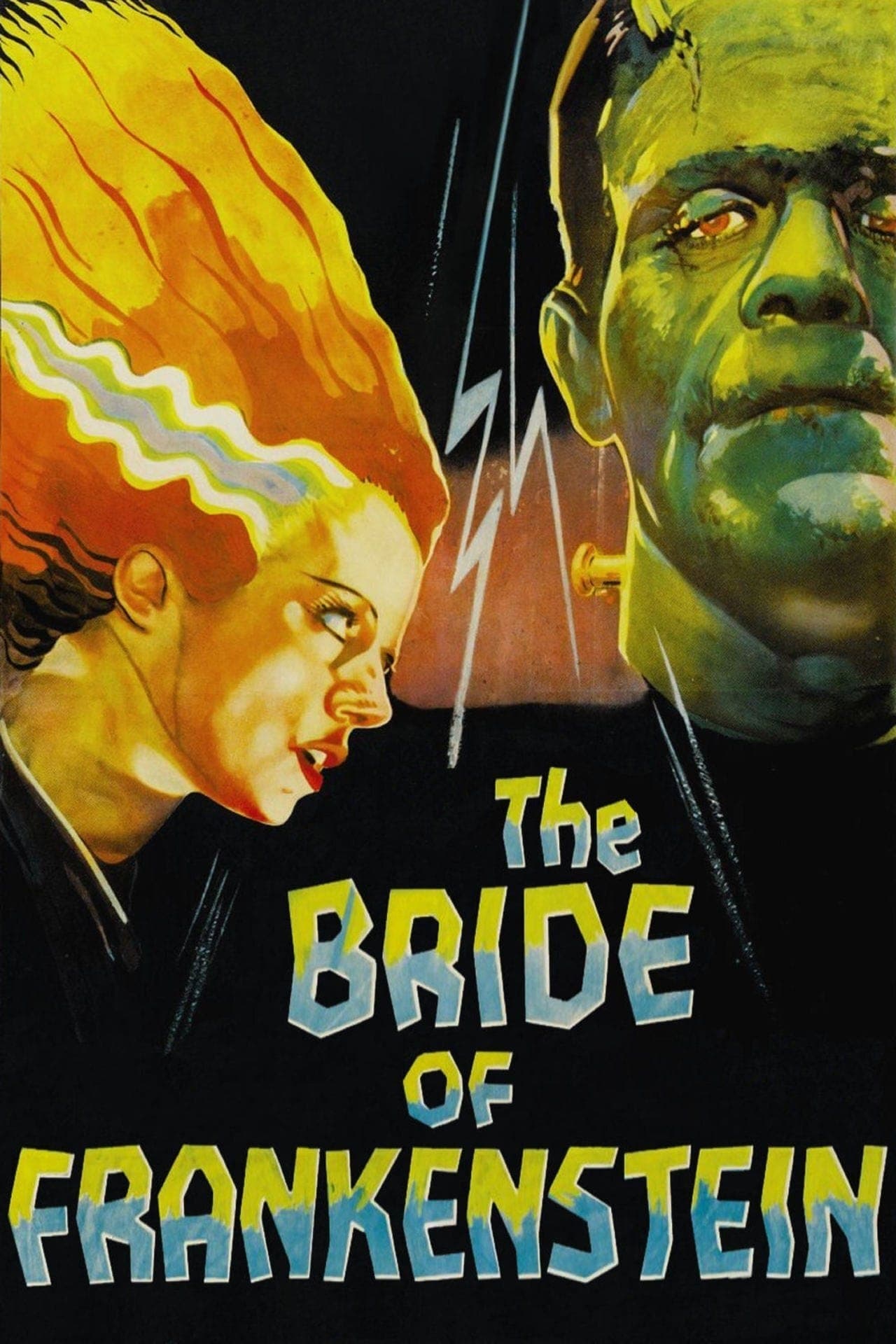

Bride of Frankenstein

1935

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

The Bride of Frankenstein, directed by James Whale in 1935, is not a mere sequel, but a work that transcends its predecessor, rising to heights of lyricism and unease rarely achieved in the genre. At a time when cinema, and particularly horror, was beginning to consolidate its stylistic features, Whale, with a creative freedom that reflected his idiosyncratic artistic vision and refined theatrical sensibility, went far beyond the formula of mere entertainment. He did not merely rehash, but with almost philosophical audacity, delved deeper into the themes already sketched out in the first film, exploring with unexpected sensitivity and macabre humor the monster's existential solitude and the most abyssal and uncontrolled side of scientific ambition. The addition of memorable characters like the sinister Dr. Pretorius, masterfully played by Ernest Thesiger, an actor with an ethereal physicality and perfect diction, imbues the film with a patina of decadence and cynicism that sets it apart. Pretorius is not just a villain, but a catalyst of dissolution, a true infernal demiurge who pushes Dr. Frankenstein towards a moral abyss, enriching the narrative with gothic nuances and a perverse, almost Mephistophelian, irony. Furthermore, the presence of the well-established Karloff, whose performance is now a paradigm of how body and mime can express a tormented soul even without the aid of words, imbues the narrative with a creeping sense of terror that merges with a palpable and heartbreaking pathos, transforming the monster from a nightmare creature into a tragic, and in some ways romantic, anti-hero.

The story picks up from the ending of the first film, reconnecting with a naturalness that belies the hurried gestation of the sequel. Professor Frankenstein, tormented by his hubris and the disastrous consequences of his experiments, intends to definitively conclude his scientific endeavors to find peace in marriage with his beloved Elizabeth. But it is precisely at this moment of apparent redemption that the seductive and corrosive figure of Pretorius bursts in. The latter, with his collection of miniature homunculi – a macabre cabinet of curiosities that evokes the alchemical obsessions of the Renaissance – shows Frankenstein the results of his delirious experiments on the creation of life, attempting to induce him to continue his work. Pretorius's objective is to give the monster a companion, a distorted echo of Adam's desire for Eve, but here imbued with a nihilistic and almost blasphemous ambition. Upon Frankenstein's refusal, as he desperately tries to escape his past, Pretorius does not hesitate to blackmail him, orchestrating Elizabeth's abduction by the monster. This event triggers a frenzied escape, an odyssey of terror and despair that drags the monster through dark woods and hostile villages, pursued by an ignorant and vengeance-thirsty mob. This journey through a world that rejects diversity and the unknown represents not only an evident metaphor for the harrowing condition of marginalization and solitude that unites both the monster and his future, albeit reluctant, bride, but also a bitter commentary on human nature and its inability to confront what deviates from the norm. In his tragic wanderings, the monster experiences systematic rejection, but paradoxically also learns to communicate, to express a deep desire for connection, making his isolation even more poignant.

A visually extraordinary work, the film employs expressionistic cinematography that, through the masterful use of light and shadow, creates a gothic and dreamlike atmosphere of rare intensity. The distorted shots, the elongated shadows dancing on the walls of laboratories and mausoleums, and the close-ups laden with pathos reveal a clear influence of 1920s German cinema, evoking masterpieces like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu. Kenneth Macgowan's set designs are not mere backdrops, but veritable silent characters, imposing and detailed architectures that amplify the sense of claustrophobia and macabre grandeur, from damp crypts to alchemical laboratories overflowing with alembics and Tesla coils. Jack Pierce's makeup, moreover, is pure iconography: if Karloff's monster is a work of art of prosthetics and scars, his bride, with her wispy hair and zigzag scars on her neck, has entered the collective imagination as the very symbol of mutated beauty and perverse creation, an icon destined to endure far beyond the genre's boundaries. The sound, too, with its hisses and unsettling grunts, contributes to building an immersive and deeply disturbing experience.

Whale's direction manages to balance, with an almost alchemical mastery, pure horror, biting dark humor, and moments of profound, disarming pathos, creating a striking synthesis of dark comedy, gothic horror, and dramatic narration. This is not just a frightening film; it is also entertaining, even playful in its macabre irony. Whale's conscious camp, evident in figures like Pretorius or the very gestation of the bride, adds a layer of complexity that elevates the film beyond simple genre narrative, anticipating post-modernity by decades. It is an approach that reflects the director's unique sensibility, his ability to infuse the narrative with a vein of subtle subversion, almost a mocking smile in the face of horror.

The film acutely and without moralizing explores the typical themes of 19th-century gothic literature: death as a permeable boundary, resurrection as an act of divine emulation, the creation of artificial life as a challenge to the limits imposed by nature, and the potential divine punishment for human arrogance. The figure of the monster, created by man and then mercilessly rejected by society, sublimely embodies the theme of marginalization, of the inescapable solitude of the Other. He is the modern Prometheus, a being who carries within him the fire of life but is condemned to an existence of torment and rejection, a pariah whose sole desire is to find a kindred spirit, a partner in existence. Meanwhile, the figure of the bride, whose brief appearance is of devastating intensity, destined for a tragic existence and an equally lacerating rejection, represents the fragility of contaminated beauty and innocence brutally violated by unnatural creation. Her terrified reaction to the monster, that sharp, primordial scream, is the culmination of the tragedy, the definitive rejection that shatters all hope of union and understanding, condemning both to an impossible existence.

The Bride of Frankenstein is not merely a horror classic, then, but a film that reflects in a surprisingly contemporary way on the fears and contradictions of modern man: his insatiable thirst for knowledge, the uncontrollable drive for progress, and the inherent danger in overstepping ethical and natural boundaries. In an era of rapid scientific advancements and growing social anxieties (not least the Great Depression, which sharpened the sense of precariousness and fear of the "other"), Whale's film stands as a warning, a parable on creative responsibility and the consequences of the abuse of power. It is a work that, though shrouded in gothic mists, resonates with an almost prophetic power, questioning the very nature of humanity and its capacity (or incapacity) to accept and love what is different, even what it itself has generated. A layered masterpiece, inviting continuous re-reading, always revealing new nuances between terror and pity.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...