A City of Sadness

1989

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

City of Sadness is a work of austere beauty and quiet power, a requiem for an entire nation and its long-silent memories. With this masterpiece, Taiwanese master Hou Hsiao-Hsien performs an act of political courage and cinematic mastery that is almost unprecedented: it is the first film to break a forty-year taboo, directly addressing the founding trauma of modern Taiwan, the Incident of February 28, 1947, and the subsequent “White Terror.” But he does so with a language that is the antithesis of loud denunciation. His is a whispered chronicle, an elegy that finds the horror of history not in images of violence, but in the voids it leaves behind, in the silent rooms and broken destinies of a family.

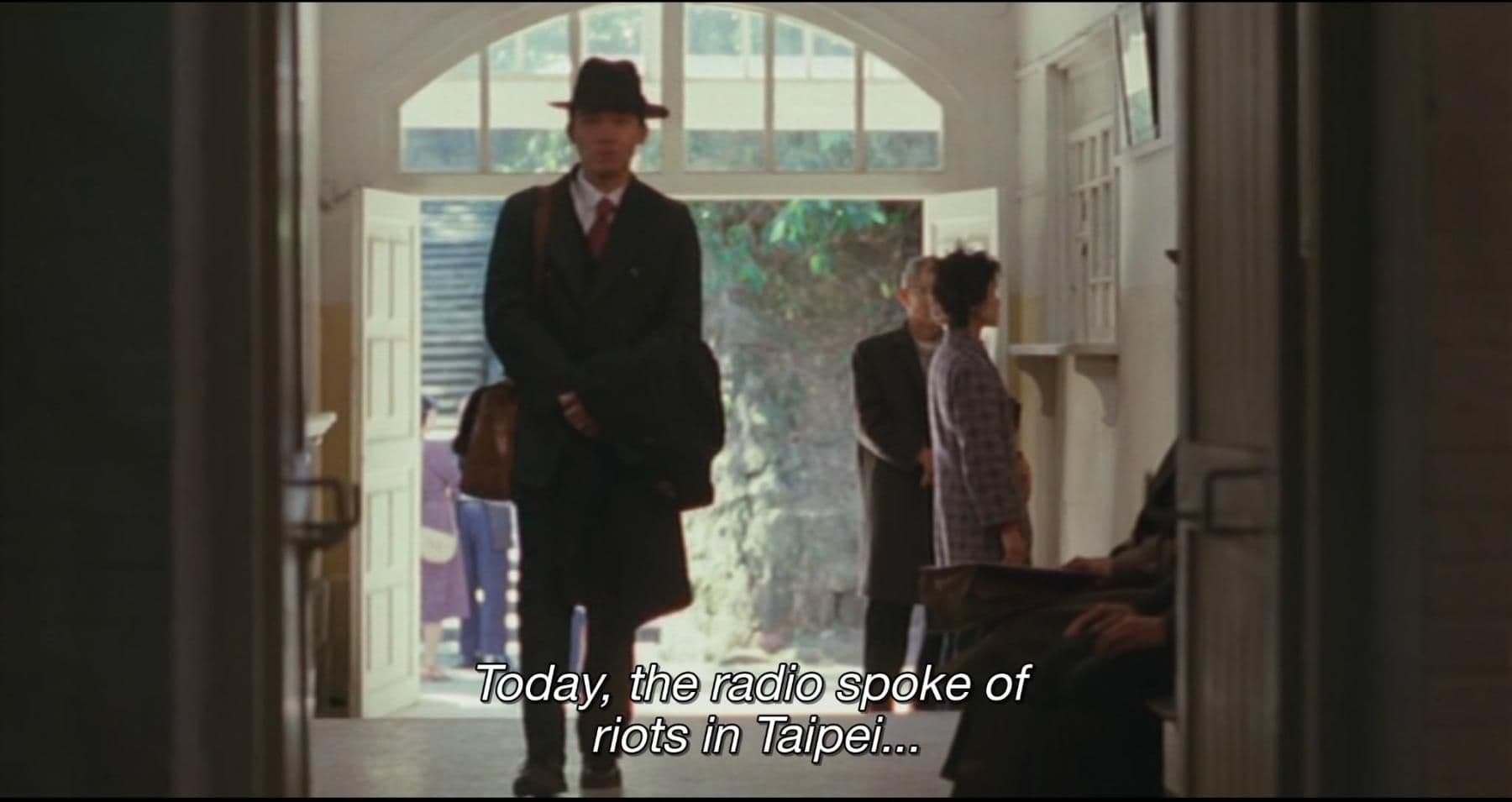

The story takes place in a historical period as complex as it is crucial, between 1945 and 1949. With the Second World War and fifty years of Japanese occupation over, the island of Taiwan is “reconquered” and handed over to the Chinese nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang. What should have been liberation quickly turns into a new, and in some ways more brutal, form of colonization. The film recounts this chaotic period of transition through the painful events of the Lin family, whose fate becomes a microcosm and allegory of the fate of the entire nation. The four Lin brothers embody the different, tragic trajectories of a people trapped between two empires. The eldest, Wen-heung, is the traditionalist, a bar owner who tries to maintain a balance but ends up crushed by the corruption and violence of the new arrivals. The third son is a ghost, lost in the war in the Philippines. The second, traumatized by the war, becomes involved with the Shanghai underworld and is driven mad.

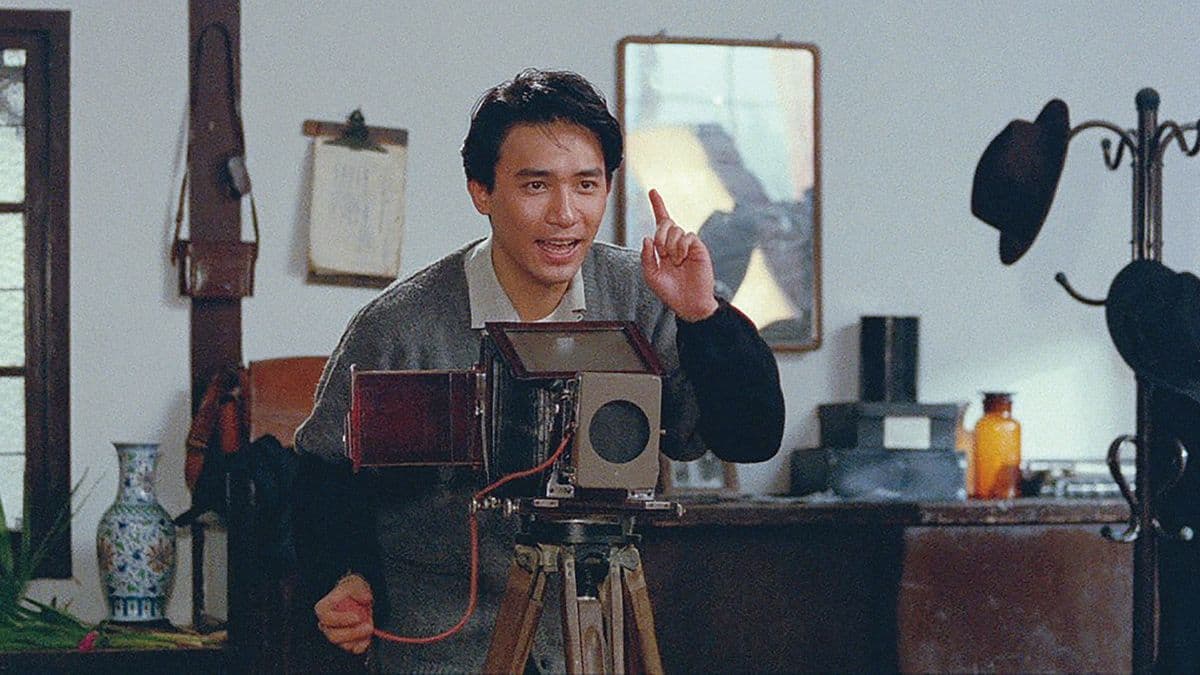

And then there is the fourth and youngest brother, Wen-ching, played by a very young and already immense Tony Leung. He is the heart and conscience of the film. A professional photographer, he is deaf and mute due to a childhood accident. His condition is not a melodramatic quirk, but the central and most powerful metaphor of the work. Wen-ching is the very voice of Taiwan during the White Terror: a voice that has been prevented from speaking, from denouncing, from telling its own truth. He can only observe, bear witness in silence. He communicates through writing, and Hou Hsiao-Hsien, in a stroke of genius, chooses to show us his dialogues through captions, using a silent film technique to give substance to a voice that has been silenced.

The similarities with post-war Japanese cinema are inevitable, but it is above all with the master Yasujirō Ozu that Hou Hsiao-Hsien's cinema engages in the most profound dialogue. City of Sadness is, in many ways, an Ozu film thrown into the cauldron of historical tragedy. We find the same contemplative aesthetic: the predominantly static camera, the compositions framed with pictorial rigor, the use of long shots that frame the characters within their environment, and a deep attention to family life. But where Ozu used this style to capture the melancholic transformations of the post-war Japanese family, Hou uses it to create an almost unbearable tension between the quiet of everyday life and the violence of history raging just outside the frame. If one were to venture a more unusual parallel, given his ambition to recount the collapse of a world through the events of a single family, one might think of Luchino Visconti. As in Il Gattopardo or Senso, here too, great history bursts in and devastates private lives, but it does so with a style that is the antithesis of Visconti's operatic opulence.

It is precisely in the aesthetics that the capital importance of this film lies. Hou Hsiao-Hsien is a master of distance and ellipsis. He rejects the codes of Hollywood drama. He does not use close-ups to manipulate the viewer's emotions, there are no climactic scenes, there is no invasive soundtrack. His camera is often positioned at a distance, observing the characters through doors or windows, like a discreet and respectful witness. Horror, such as the Incident of February 28, is never shown directly. We perceive its consequences: sudden disappearances, whispered conversations, the terror that descends on the community. Hou understands that showing violence is often less powerful than suggesting it, that leaving horror to the viewer's imagination is an act of respect towards both the victims and the audience.

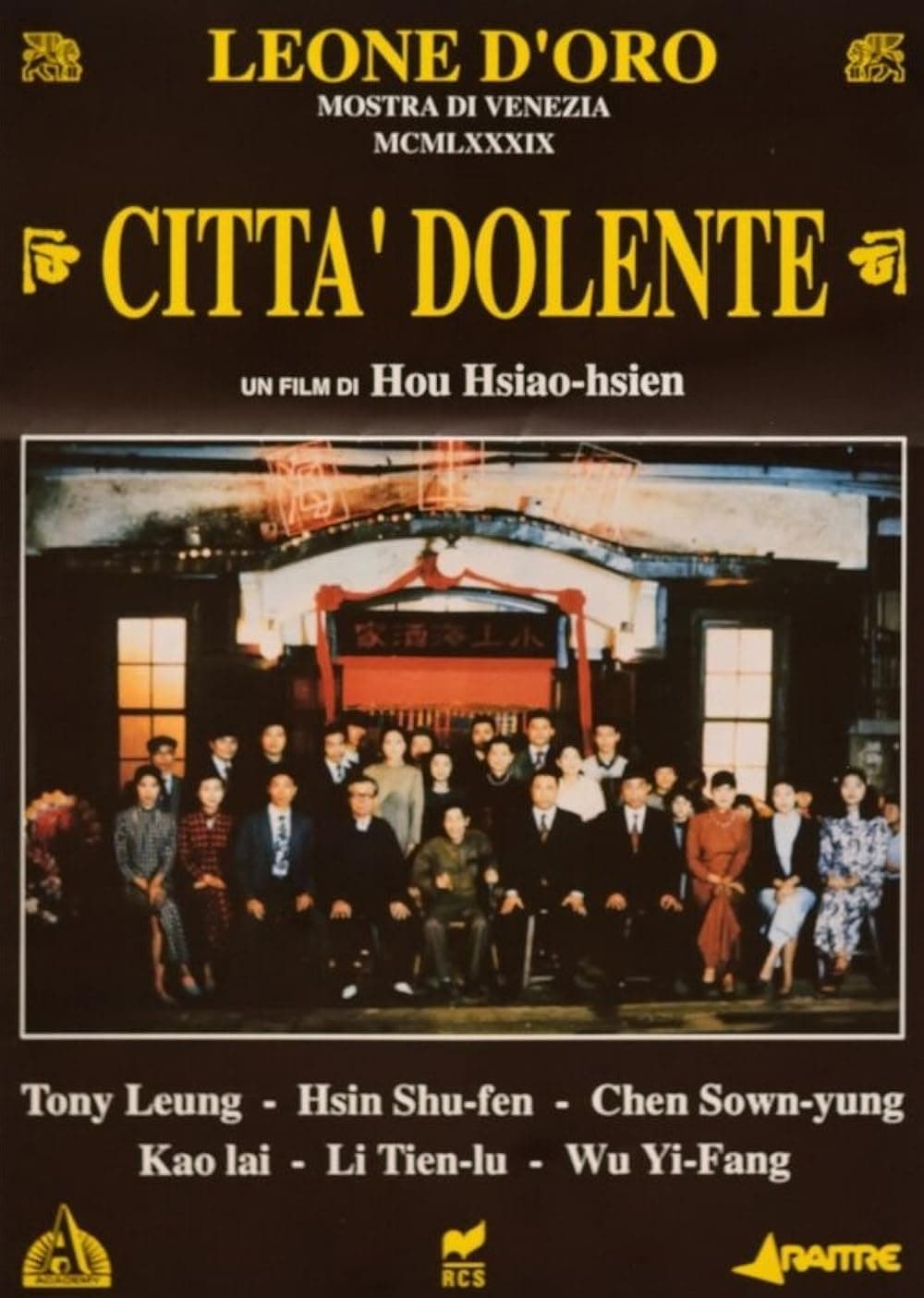

This film was not only an artistic event, but a political and social earthquake. Winning the Golden Lion at the 1989 Venice Film Festival—the first Taiwanese film to receive such a prestigious award—A City of Sadness gained international visibility and legitimacy that made it impossible to continue ignoring the story it told. It effectively opened the door to a national debate on a period that had been erased from the official historiography of the Kuomintang. It is a work that literally helped a nation recover its memory. A City of Sadness is a film that teaches us that history is not only made up of great events, but also of the small lives that are swept away, and that sometimes silence, when observed with the right attention, can say more than any scream. For its political courage, its formal rigor, and its profound, painful humanity, it is a work whose aftertaste lingers long in the mouth, like a mint leaf on a hot summer evening.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...