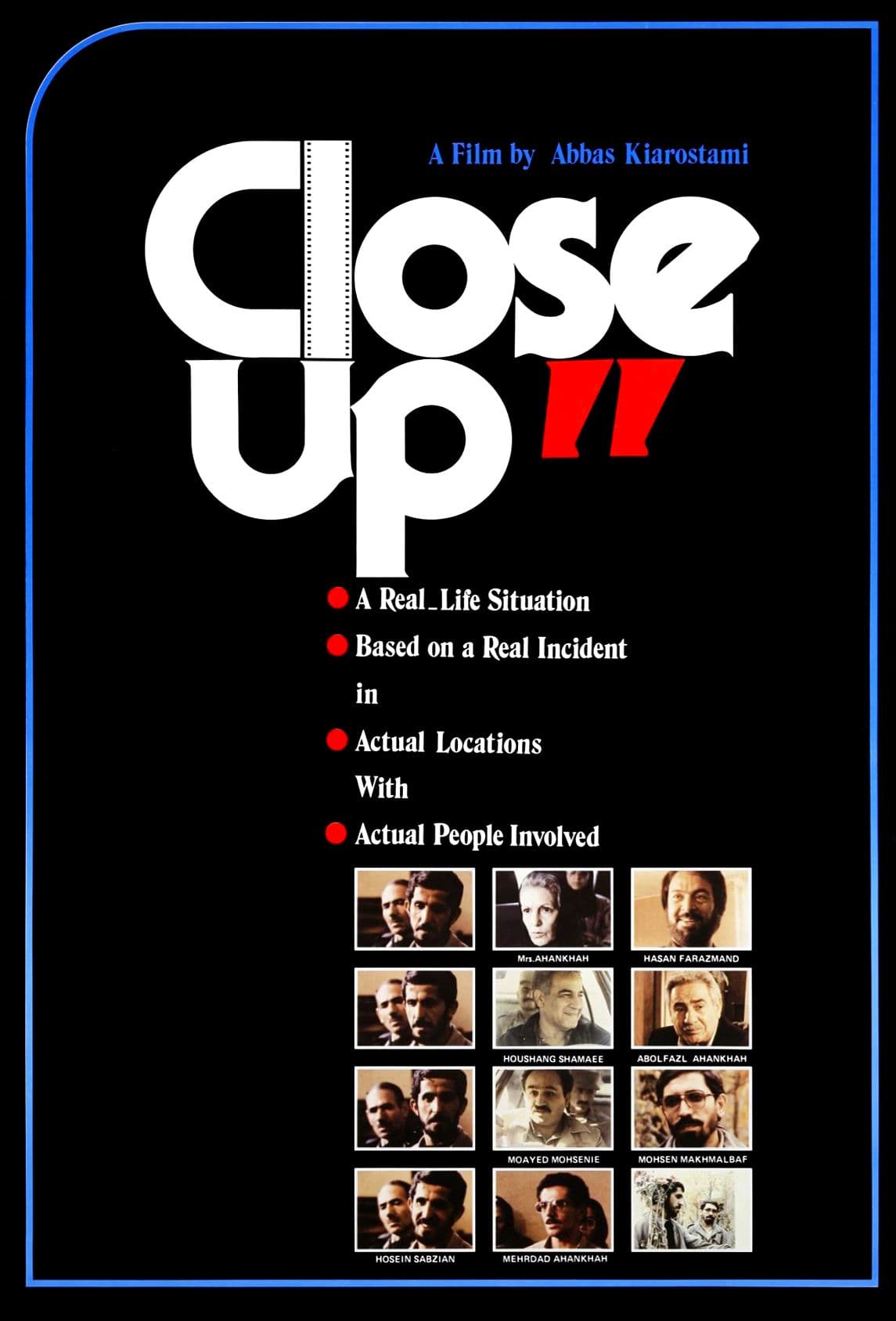

Close Up

1990

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Starting from a bizarre news story, Kiarostami constructs a labyrinth of mirrors, a philosophical puzzle that questions the nature of truth, identity, and our desperate need to be seen. It is a film that is not watched but participated in, an experience that leaves us with more questions than answers, and it is precisely in this generous uncertainty that its greatness lies. It is, without a doubt, one of the most intelligent and deeply human cinematic gestures ever conceived.

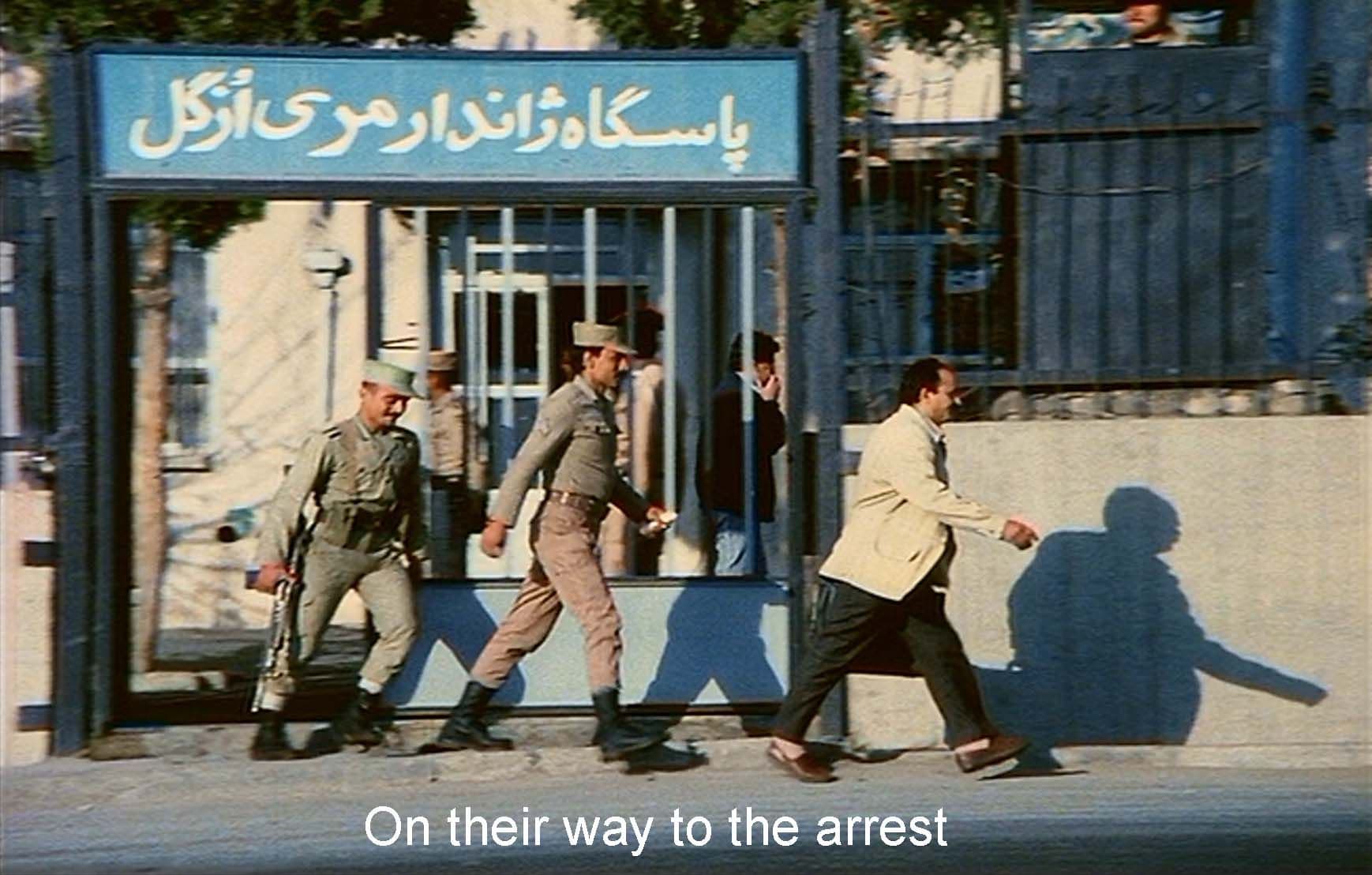

The story, in its essence, is almost surreal. A man named Hossein Sabzian, an unemployed and passionate film buff, pretends to be the famous Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf. With this false identity, he ingratiates himself with the members of a cultured bourgeois family in Tehran, the Ahankhahs, promising them a role in his next film, based on their lives and their home. The deception is inevitably discovered, and Sabzian is arrested for fraud. At this point, Kiarostami does not choose to romanticize the story, but takes a meta-textual leap of astonishing audacity: he convinces all the real people involved—the impostor Sabzian, the Ahankhah family, director Makhmalbaf, and even the judge—to participate in the film playing themselves, in a re-enactment that is both a staging and a process of elaboration.

We find ourselves catapulted into a purely Pirandellian territory. The film becomes a veritable Six Characters in Search of an Author on film, where the protagonists of a real drama are called upon to re-enact their story, not for an audience, but for themselves, in search of a truth that is no longer factual, but emotional and psychological. The courtroom, with Kiarostami's blessing, who obtains permission to film, is transformed into a stage. Sabzian is no longer just a defendant, but an actor who finally has an audience, an opportunity to explain the “why” of his actions. His is not the defense of a criminal, but the confession of a soul. We soon understand that his motivation was not financial gain, but something much deeper and more poignant: the desire for respect, to be, even if only for a few days, someone who matters.

But if Pirandello's interpretation sheds light on the game of masks and truth, another shadow is cast over the story, and it is the unmistakable shadow of Franz Kafka. The court in which Sabzian finds himself, although presided over by a humane and understanding judge, takes on the contours of an absurd Kafkaesque court. His is not a legal fault, but an existential one: the fault of having desired another identity, of having attempted to force his way into a ‘castle’ (that of art and social recognition) whose doors were barred to him. The charge of fraud is merely a bureaucratic formality masking a trial of ambition, of a desire for transcendence. His crime is a request for legitimacy presented in the wrong way, a desperate attempt to receive approval from a system that does not recognize him. Like a character in Kafka, Sabzian is an ordinary man trapped in a logic greater than himself, judged for a crime that has less to do with what he did and more to do with what he dared to desire to be.

In this, the film is a powerful reflection on the role of art and the artist in post-revolutionary Iran. For Sabzian, cinema is not entertainment, it is a form of transcendence, a secular religion. Being a filmmaker like Makhmalbaf means having a voice, being a creator of worlds, a respected identity in a society where he feels invisible. His crime is not an act of greed, but a desperate attempt at self-creation, a misappropriation of identity to escape the prison of his marginalized existence. It is a gesture born of a love for cinema so pure and all-encompassing that it becomes, paradoxically, illegal.

Kiarostami's style is the antithesis of everything sensationalist. His camera is patient, empathetic, almost Franciscan. He lingers on faces, silences, and minimal gestures. He himself is not an invisible observer, but an active participant, a mediator. It is his intervention that transforms a criminal trial into a group therapy session, an opportunity for reconciliation. His art lies in his ability to find profound poetry in the ordinary, as in the unforgettable sequence in which a spray can, dropped by a character, rolls down a sloping street for a long time. That solitary metallic sound, that small object traveling stubbornly, becomes a visual metaphor for Sabzian's quest, an insignificant detail that takes on enormous existential weight.

The culmination of this meta-textual approach is the final scene, a moment of cinematic grace of almost unbearable beauty. Kiarostami orchestrates the meeting between the real Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Hossein Sabzian, just released from prison. Makhmalbaf arrives on a motorcycle to take Sabzian to the Ahankhah family's home to ask for forgiveness. But, just at that moment, Kiarostami's microphone ‘breaks down’. The audio of their conversation becomes fragmented, distorted, almost incomprehensible. This supposed technical failure is, of course, the most brilliant directorial choice in the film. By denying us the clarity of the dialogue, Kiarostami forces us to listen in a different way. He pushes us to focus on gestures: Makhmalbaf buying a vase of flowers, the handshake, the hug. He makes us privileged witnesses and, at the same time, respectful of a moment of almost sacred intimacy, a moment that needs no words to be understood. It is the director's final statement: the deepest truth is not always found in a clear, focused close-up, but sometimes hides in the off-screen, in the unsaid, in the imperfect sound of a reconciliation. For its ability to use cinema to question cinema itself and, in doing so, to reveal universal truths about the human soul, Close-Up is not just a film to see before you die, it is a film that teaches us a new way of seeing.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...