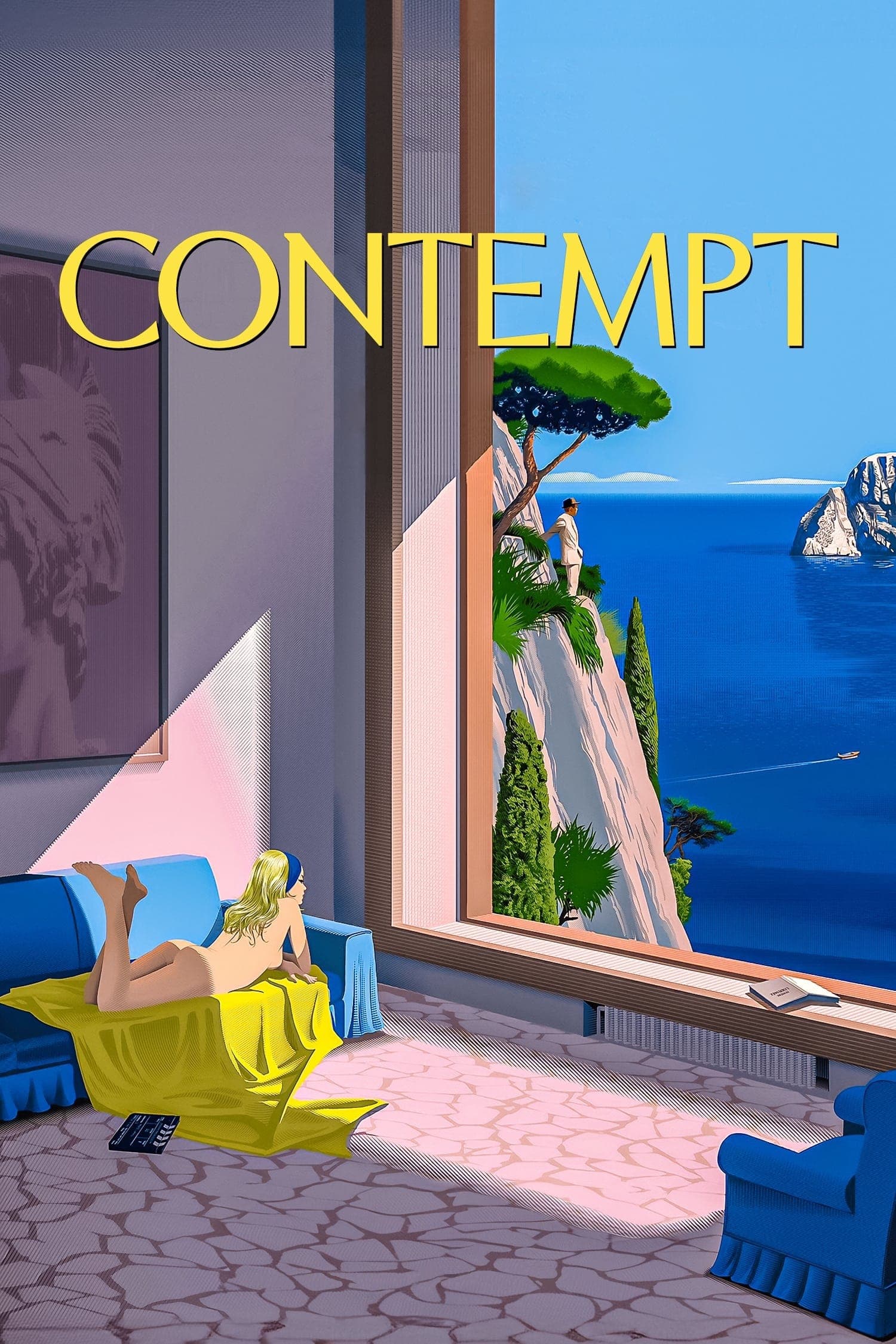

Contempt

1963

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

A work of terrible introspective power with Godard's disruptive talent free to roam the psychic microcosm of the protagonists, pitilessly laying bare their most intimate recesses. Not a mere sentimental drama, but a rigorous autopsy of a modern bourgeois soul, conducted with the surgical lucidity and disenchanted irony that would consecrate Godard as the most audacious and intellectually provocative among the Nouvelle Vague directors. Here, the Swiss filmmaker does not merely narrate a declining love story, but deconstructs cinematic language itself to investigate the fragility of communication, the commodification of feelings, and the crisis of art in the era of cultural industry. His direction, audacious and iconoclastic, rejects conventions to embrace an aesthetic of fragmentation, asynchronous editing, and the estranging use of color, transforming every shot into a visual essay on the human condition.

Add the powerful suggestion of Moravia that hovers over the entire film, and you will obtain an almost adamantine equation for a work of art to be deciphered yet also to be revered. Yet, more than a faithful adaptation, what Godard accomplishes is a true deconstruction of the novel, a meta-cinematographic reinterpretation in which the internal conflict of the characters merges and clashes with the dynamics of cinematic production itself. Contempt, for Godard, is not only Camille's towards Paul, but also the contempt of authentic art towards its commercial corruption, a theme emblematically embodied by the figure of the venerable Fritz Lang.

The story centers on the ambiguous relationship between an Italian screenwriter, Paul Javal (Michel Piccoli), a penniless and ambiguous intellectual, and an American producer, Jerry Prokosch (Jack Palance), roughly pragmatic and obsessed with profit. This dichotomy, profoundly Godardian, is not only a narrative engine but the pulsing heart of a reflection on the cultural colonization of Europe by Hollywood.

The screenwriter was called to revive the fortunes of a film directed by Fritz Lang (who plays himself, in a kind of "meta-cameo"). His presence is by no means accidental, nor purely celebratory. Lang, the master of German Expressionist cinema, here embodies the purity of European art, its philosophical integrity, and its resistance to the siren call of Hollywood profit, represented by the cynical American producer. His character becomes a kind of moral counterpoint, a blind Tiresias who does not see, but "feels" the wrong direction the industry is taking, and at the same time a declaration of Godard's own artistic intent. It is in this clash between Lang's vision – who wants to film the Odyssey as an authentic, non-commercial epic poem – and Prokosch's demands – who only desires a commercial product with nudes and special effects – that the film reveals itself as a keen commentary on the very genesis of "Contempt" and on the troubled relations between Godard and the American producer Joseph E. Levine, an affair that significantly mirrored the work's narrative tensions. The film itself, in fact, was born from a commission that expressly required the presence of Brigitte Bardot and nude sequences, elements that Godard sublimated or, rather, subverted for his own artistic ends, transforming them into a critique of their very use.

The writer's wife, Camille (Brigitte Bardot), feels a surge of repulsion towards her husband's overly subservient attitude towards the American. Her reaction is not only emotional but deeply symbolic, mirroring the dignity that art and love risk losing when subjected to the laws of the market.

Things will escalate when the woman becomes convinced she is being used as a bargaining chip for her husband's professional ends. This theme of commodification is not limited to Camille's body but extends to their relationship itself, which is emptied of authenticity, transforming into a silent and desperate negotiation.

The inner conflict of Brigitte Bardot is sensational: in how it is highlighted, how it is narrated, and how it is filmed. Her Camille, far beyond the simple erotic icon that the film industry and press of the time had stitched onto her, is here a figure of agonizing complexity. Godard films her with an almost painful reverence, often isolating her in shots that enhance her vulnerability, contrasting her sculptural beauty with her inner dissolution. The famous apartment sequence, which occupies a significant part of the film and unfolds with an almost theatrical lucidity, becomes the quintessence of this relational autopsy. Through a series of seemingly trivial dialogues, alternating with long silences dense with unspoken meanings, Godard paints a merciless fresco of a couple's slow descent into the abyss of the unsaid and resentment. It is here that his gaze becomes more incisive, showing how Camille's physical nudity in the opening progressively transforms into the emotional nakedness of an exposed soul, which feels no longer loved but possessed, no longer understood but used.

A totally psychological dimension that cannot but intrigue, fascinate, even captivate the viewer, who thus becomes a morbid voyeur of a mind laid bare specifically for them. It is not a morbid voyeurism in the most voyeuristic sense of the term, but rather an almost Brechtian invitation to observe the mechanics of disintegration, the ordeal of a love that fades under the weight of accumulated misunderstandings and an almost fatal inability to communicate. The use of saturated colors – the intense blue of the Capri sea, the vivid red of Camille's dress – violently contrasts with the glacial coldness of feelings, creating an aesthetic of disillusionment that is as visual as it is emotional. Georges Delerue's poignant score, with its melancholic leitmotif, amplifies this feeling of irreparable loss, lending a universal resonance to the intimate drama. "Contempt" thus stands not only as a merciless portrait of a relationship in crisis but as a keen reflection on the very nature of art and its integrity in the face of commercial pressures. It is a film that challenges, questions, and ultimately condemns, but does so with a formal beauty and intellectual depth that render it immortal, a timeless masterpiece whose "terrible introspective power" continues to resonate, inviting every new viewer to decipher its mysteries and confront its uncomfortable truths.

Genres

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...