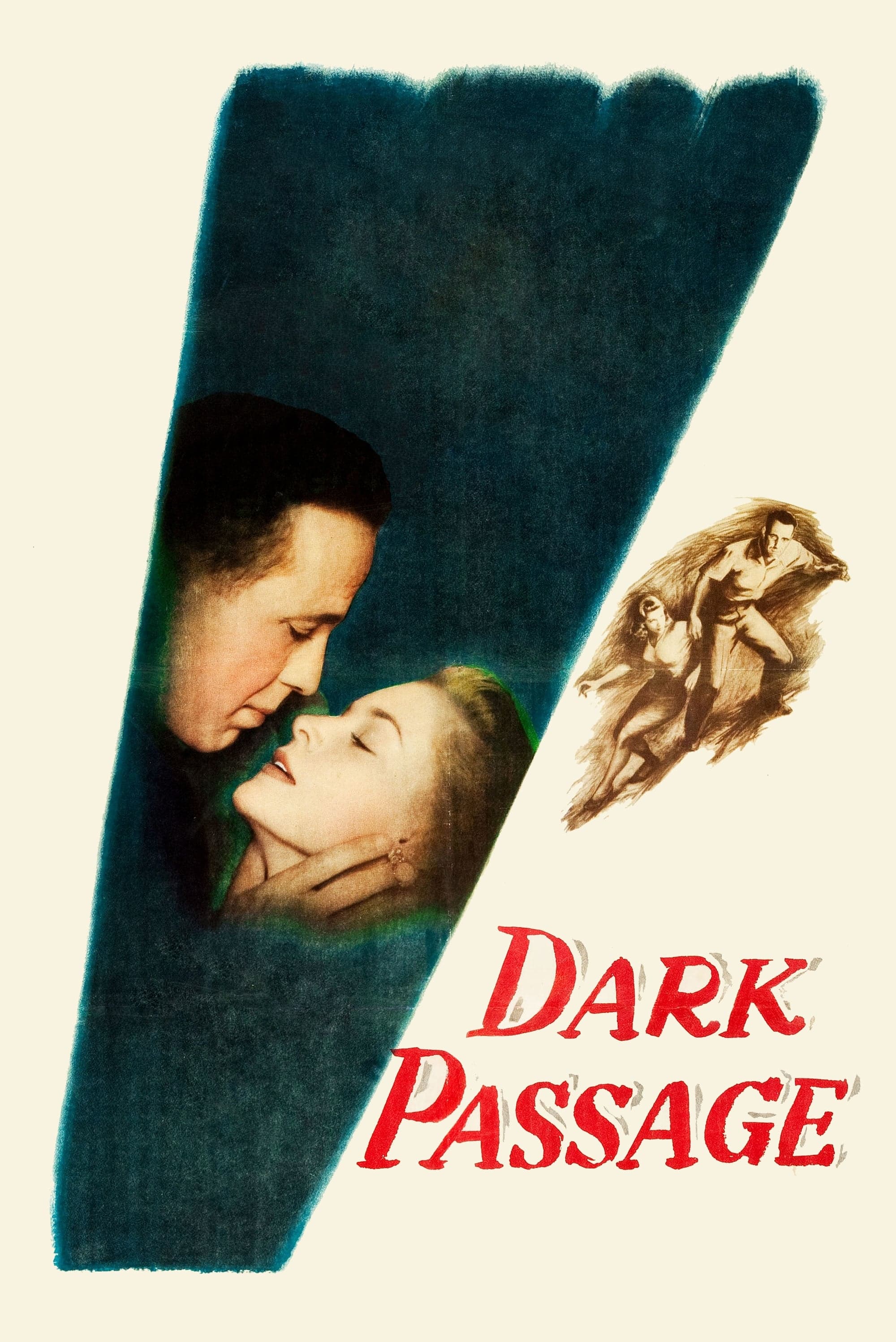

Dark Passage

1947

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Dark Passage, the dark gem embedded in the heart of classic noir, effectively represents the first true archetype whose narrative core is centered on the Topos of the man on the run. It is not a simple escape, nor a common chase, but rather a psychological odyssey, a journey through the labyrinths of lost identity and paranoia. The story, based on the novel of the same name by David Goodis, a master of hard-boiled fiction whose dark and disillusioned prose provided vital nourishment for many of the genre's most representative works, features Vincent Parry, a man unjustly accused of murdering his wife who, through a daring escape, manages to break out of prison and then undergoes drastic plastic surgery, not only to evade his pursuers, but to escape himself, a face that condemns him, an existence that has been torn from him.

Delmer Daves' audacity in confining the viewer to the protagonist's claustrophobic perspective for the first hour of the film, through a strictly subjective point of view, is not merely a technical expedient, but rather a profound immersion into Vincent Parry's disorienting reality. We do not see his face, but we perceive his every labored breath, every menacing shadow, every whisper of fear. This radical choice amplifies the sense of alienation and loss of identity that is at the heart of the narrative. Bogart's face, once revealed after the surgery, is not just the face of an iconic actor, but the materialization of a rediscovered identity, or perhaps one forged ex novo, a symbol of the transition from an interior, subjective, and fragmented vision to a more concrete, albeit still precarious, reality. It is an almost Dadaist cinematic moment, an act of re-creation of the character before the audience's eyes, reflecting the theme of metamorphosis and the search for a new truth.

Although fiercely hunted by a flawed judicial system and individuals driven by personal resentment, the man finds unexpected help and love from a woman he meets by chance, Irene Jansen. Lauren Bacall, with her magnetic presence and her husky voice that cuts through the air like a sharp scalpel, portrays Irene not as the classic femme fatale of noir, but as a complex and ambiguous figure, herself on the fringes of a conventional existence. Irene offers Parry not perdition, but an unexpected anchor, an emotional refuge in a drifting world. Their partnership is forged by marginalization, an alliance against universal injustice. Together they emigrate, in an ending that, although idealized by the Hays Code, offers a glimmer of hope, the possibility of starting a new life, if not free from the past, at least far from its suffocating grip.

The central theme of the work is, for the first time, not the detective story itself (of which the true killer is almost immediately discernible), but the concept of a man without reference points, deprived of friendships, of a recognized social milieu, and even of his own humanity. This is the beating heart of the purest noir: existential solitude, the post-war paranoia that permeated American society, the sensation of being a fish out of water in a hostile world. Parry is the embodiment of alienation, a lost soul navigating by guesswork in a sea of shadows and lies. His escape is not only from a physical prison, but from the prison of a stolen identity, from the condemnation of being a "nobody" to the law and an "everyone" to his conscience.

The protagonist's redemption through his gradual detachment from that society which so animalistically hunts him is perhaps the ultimate message Daves wishes to convey through the camera. Daves, far from being a mere craftsman, demonstrates a profound understanding of human psychology, masterfully tracing Parry's path towards a form of inner freedom, paradoxically achieved through voluntary marginalization. It is a bitter redemption, certainly, one that does not erase the pain, but allows the character to rebuild, brick by brick, a sense of dignity and belonging, not within the social context that expelled him, but in the relationship with the only person who was able to see him beyond his status as a fugitive. This theme anticipates certain existentialist currents of European cinema, where salvation is not a divine gift, but an arduous and deeply personal conquest.

Bogart's performance is precise and perfectly focused, as he is always at ease in dark and mystifying roles. His face, initially invisible, then bandaged, finally revealed with its scars (visible and invisible), becomes a palimpsest upon which the character's entire odyssey is inscribed. Bogart, with his inimitable ability to express cynicism and vulnerability with a single glance, embodies Parry's despair and tenacity with a mastery that has consecrated him an eternal icon of cinema.

To reunite the proven Bacall-Bogart duo, whose combined charisma guaranteed box office success, considerable pressure was put on their respective agents, and it is said that their fees skyrocketed. Warner Bros., far-sighted in capitalizing on their undeniable chemistry and their status as beloved public figures, knew it had a winning formula. And it all, naturally, worked perfectly: the film was a true commercial success, not only solidifying the legend of Bogart and Bacall as Hollywood's golden couple, but also cementing Dark Passage as one of the cornerstones of that crepuscular cinema, made of shadows and anxieties, which still fascinates us today with its timeless modernity. Its influence can be found in countless subsequent thrillers, testifying to its archetypal nature that shaped the genre and our perception of the man on the run.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...