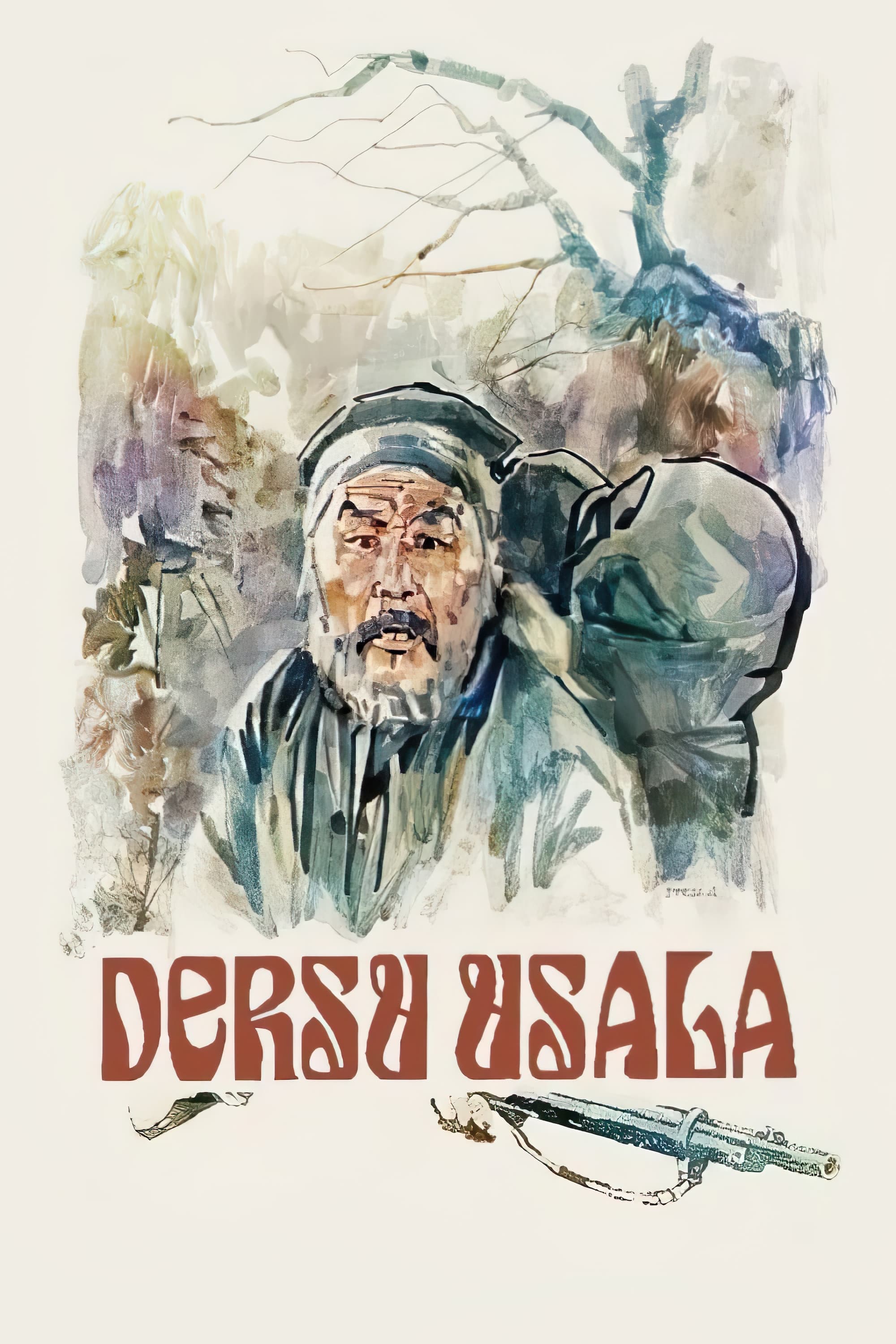

Dersu Uzala

1975

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Kurosawa transcends his own style and for once abandons the Japanese milieu to tell the story of a Mongolian hunter, a mystical creature in communion with a maternal yet tremendously hostile nature. If in other works the director has plumbed the depths of the human soul through the samurai codes of honor or the harsh realities of post-war Japan, in Dersu Uzala his lens focuses on an archetype of primordial wisdom, a man whose connection with the surrounding environment transcends all social convention and Western logic.

Drawn from the travel book by the Russian scientist and explorer Arseniev, Dersu Uzala represents only formally a semantic deviation in Kurosawa's language. In reality, his poetic vision of things is always present, enveloping the viewer in a soft aura of whispered legend, of small, precious gestures that reveal universal truths. It is the most intimate, most meditative Kurosawa, a master who finds in the story of a singular cross-cultural friendship an opportunity to express a profound and unconditional humanism, capable of overcoming linguistic barriers and the most abyssal differences. The adaptation of Arseniev's memoirs is not a mere transposition, but an elevation of the source material to a philosophical and existential plane, a palimpsest in which the explorer's personal experiences become a parable about the encounter between civilization and untamed nature.

In 1902, in an era of exploratory fervor and Russian imperial expansion in the Far East, Arseniev is with a scientific and cartographic expedition along the Ussuri River, in a wild land on the borders of Manchuria and Siberia, home to indigenous populations like the Goldi (Nanai) and the Udege. The tremendously adverse conditions of an unexplored and unforgiving territory severely challenge the expedition, on the brink of disaster, but the intervention of a mysterious character, a nomadic hunter named Dersu Uzala, proves providential. It is not merely a matter of physical survival; Dersu, with his supernatural ability to read nature's signs and anticipate its whims, introduces civilized man to a forgotten dimension of existence. His presence is a living lesson in humility and interdependence.

Slowly, Arseniev manages to break through the shell of incommunicability that separates him from the man, eroding distrust and building with him a deep friendship that transcends every social, cultural, and generational bond. It is not a hierarchical relationship, but rather an equal dialogue, almost a mutual apprenticeship, in which the explorer, holder of academic knowledge, learns from the hunter an ontological wisdom, forged by direct experience and an intuitive understanding of the cosmos. The friendship between these two men, seemingly so distant, becomes the pulsating heart of the film, a hymn to the human capacity to recognize the other beyond any categorization.

He will thus be led by Dersu Uzala into a world made of "little men," an animist vision in which the sun and moon are strong creatures, endowed with their own will, as are the wind, water, and fire. Every natural element, every animal, every atmospheric phenomenon is permeated by a vital force, by a spirit that demands respect and careful observation. It is not mere superstition, but a hermeneutics of nature, a poetic and anthropocentric vision (in the sense of relational, not dominating) that closely resembles the animist culture of certain populations strongly connected to the territory in which they live, such as the African Maasai, Amazonian Indigenous peoples, or Australian Aboriginals. This perspective, almost prophetic for the time the film was made (1975), underlines the importance of ecological harmony long before environmental issues became a dominant theme in global debate. Kurosawa shows us how "civilization," with its craving for domination and its inability to listen, is destined to destroy not only the environment but also the spirit of its guardians.

Kurosawa is extraordinary in capturing on film the intensity of the union between man and nature, the immaculate purity of a man detached from any civil context. His direction becomes almost ethereal, allowing the vastness of the Siberian landscape and the immense power of natural elements to become characters in their own right. The wide shots, which often reduce human figures to tiny dots against a backdrop of boundless forests or icy expanses, emphasize the smallness of man in the face of the grandeur of creation, but also his resilience and adaptability. At the same time, intense close-ups on Dersu, played with moving gravity and dignity by Maxim Munzuk, reveal an ancient soul, sculpted by life and the elements, repository of a wisdom that modernity has lost. The cinematography, masterfully curated, captures the changing lights of the seasons, the rigor of winter and the effervescence of spring, transforming every scene into a vivid and pulsating painting.

A work that exudes lyricism and moves with the extraordinary power of its images, Dersu Uzala is a testament to Kurosawa's genius, a film that, while departing from his usual theater of battles and social dramas, proves to be one of his most penetrating studies on the human condition. The intrinsic melancholy of the narrative, culminating in Dersu's tragic and inevitable fate, having become unable to live in the "world of little men" without nature, is not a mere lament, but a powerful warning. It is a lament for the loss of ancestral knowledge, for the disappearance of a way of being that modernity can neither comprehend nor embrace. The Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, earned in an unprecedented Soviet co-production, was an international recognition not only of the film's aesthetic beauty but also of its universal resonance, an echo that continues to reverberate, inviting us to reflect on our place in the world and the price of progress.

Countries

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...