Freaks

1932

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A film that immediately entered legend: ignobly butchered by censorships worldwide, forbidden for over 30 years in Europe, even disavowed by its own production company (Metro Goldwyn Mayer), all this due to the supposed scandalous content depicting the physical deformity of the protagonists. The echo of that rejection, almost an expulsion from the respectable Hollywood society of the time, still resonates today, transforming the film into an icon of courage and scandal. Its troubled genesis and subsequent damnatio memoriae are not a mere anecdote, but the quintessence of its impact: "Freaks" openly challenged the nascent dictates of the Hays Code and the moralistic hypocrisy that was about to engulf the film industry, revealing an uncomfortable truth that Puritan America of the 1930s was not yet ready to confront. In reality, it is a small masterpiece in its fierce juxtaposition of normality and diversity, a sublime dichotomy between psychological cruelty and the cruelty of nature. This fierceness is not only narrative but visual and emotional, exploring the profound inhumanity of a world that elevates aesthetic perfection to a parameter of value, condemning anyone who lacks it. "Freaks" is a film that radically and provocatively addresses the theme of the "other," questioning the aesthetic and moral canons of American society in the 1930s, whose freak shows were at once an attraction and a warning, a distorting mirror of collective fears. Browning, with his ataraxic and unprejudiced gaze – an approach he had already explored with his "monsters" in previous films such as "The Unholy Three" or the renowned "Dracula," albeit with masked actors – invites us to look beyond physical appearance, to recognize the humanity and dignity of those considered "monsters." He, who had an intimate knowledge of the circus world, having worked there in his youth, does not seek sensationalism for its own sake, but a deeper truth, almost an ethics of perceptual subversion.

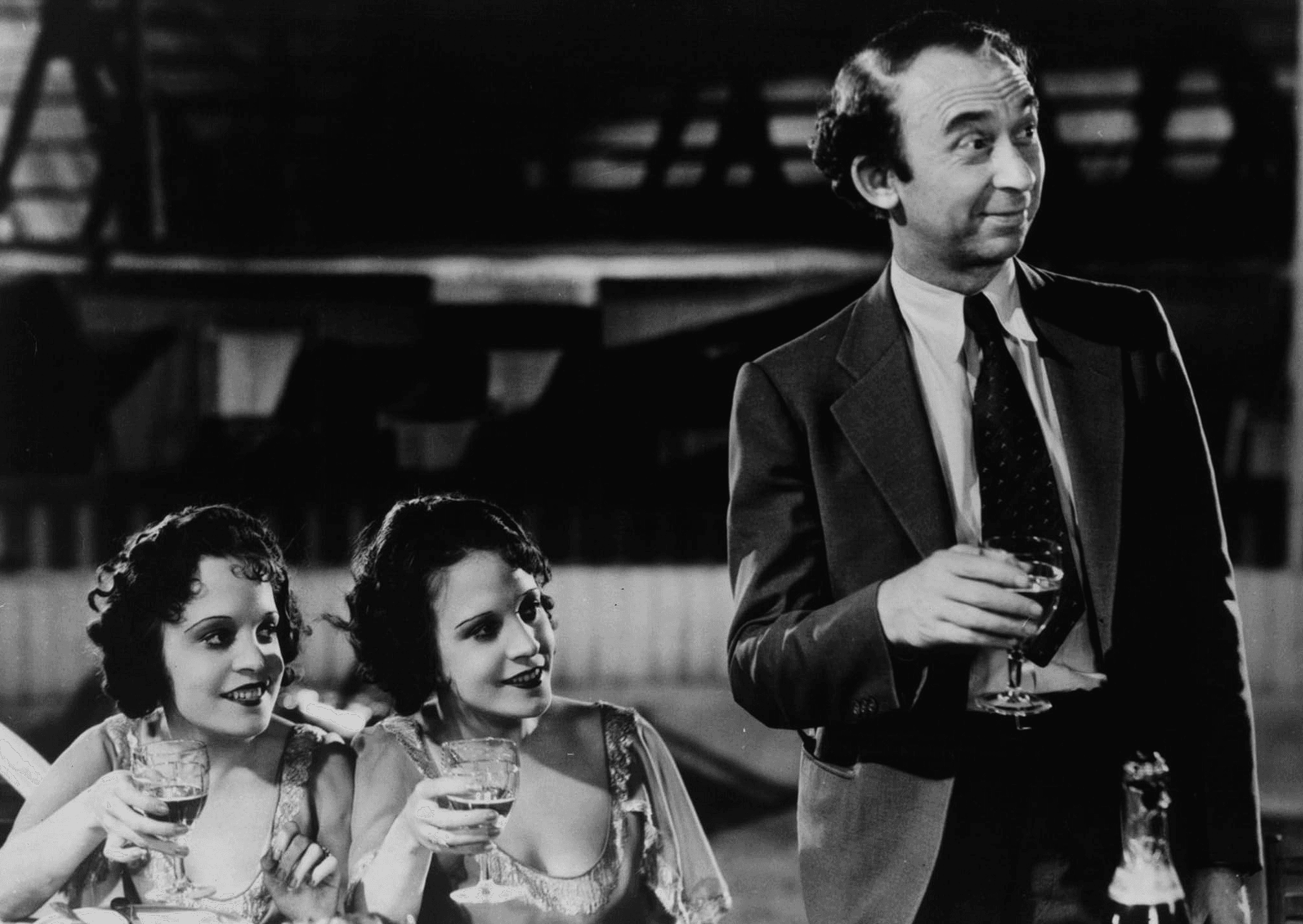

The plot, concentrated in just over an hour, revolves around the story of Cleopatra, a ruthless trapeze artist who seduces and marries Hans, a wealthy and naive dwarf, with the intention of killing him to take possession of his inheritance. Cleopatra despises the circus "freaks," considering them monstrous and repulsive creatures, with a disdainful arrogance that embodies the blindness of a society unable to see beyond the surface. Her moral abjection, far more deformed than any physical anomaly, becomes the true horror of the film. But the "freaks," guided by a strong sense of community and solidarity, a kind of "family" more authentic and loyal than many conventional ones, discover her plan and decide to take revenge, transforming Cleopatra into one of them. Their sense of justice, though primitive and brutal, stems from an unyielding cohesion, a pact of mutual protection that challenges the ruthless individualism of the outside world. The iconic wedding banquet scene, with the choral chant "Gooble gobble, one of us!", is not merely a moment of macabre acceptance, but a forced initiation ritual, a baptism in blood and belonging that seals their exclusive bond. Browning, with a chilling and memorable ending, irrevocably reverses the roles of victim and executioner, showing how true monstrosity resides in the human soul, and not in physical appearance. Cleopatra's punishment is not only revenge, but a bitter irony of fate, which forces her to physically embody the "monstrosity" she so morally abhorred, an ancestral warning about hubris and its consequences.

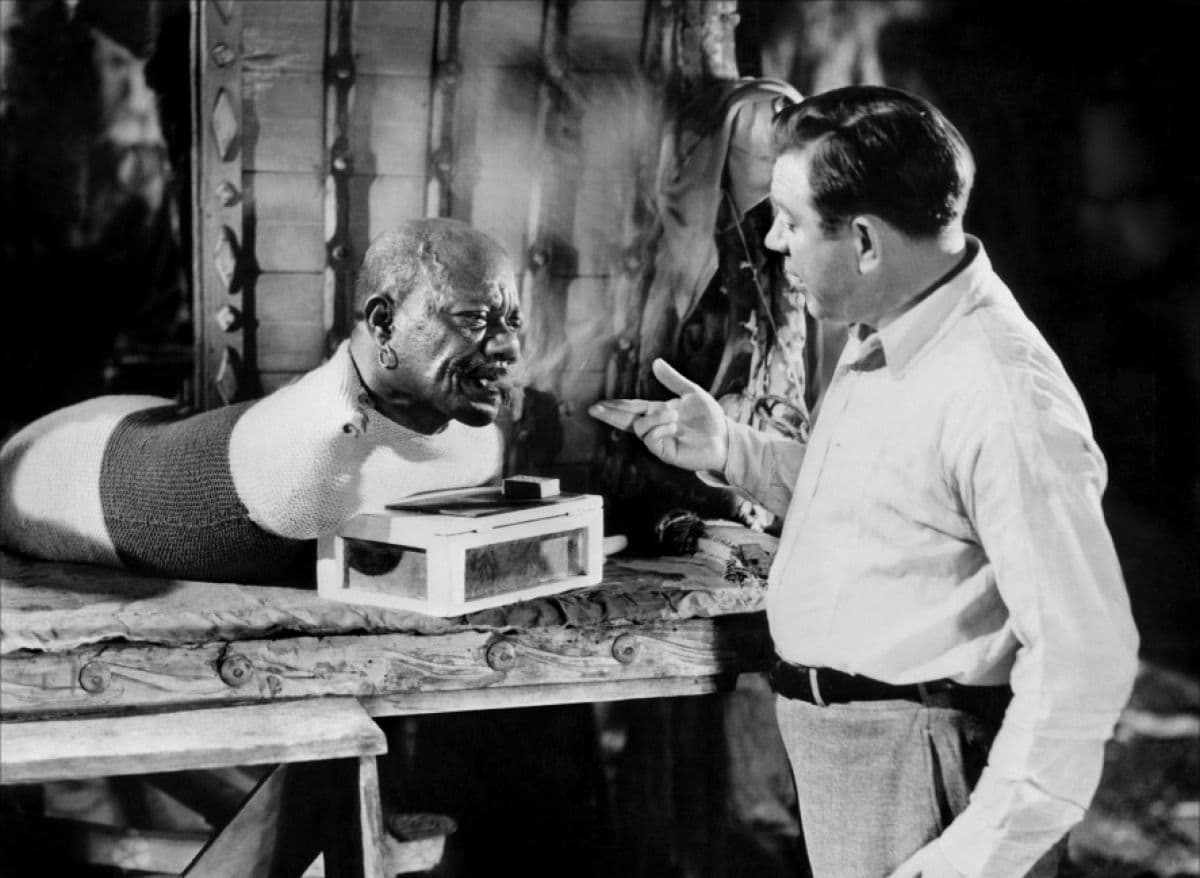

A film of shocking modernity, shot with a sublime technique in which furious long takes lead the viewer through the rotten soul of the protagonist and into the tormented flesh of the freaks. Browning, perhaps influenced by the raw realism of German expressionist cinema and its ability to deform reality to reveal inner truths, employs these long shots not only to show, but to immerse, to force the eye to linger on the figures and faces, disarming any temptation to look away. He uses the grotesque and the macabre to create a sense of unease and fascination in the viewer, a dualism that transcends pure shock to arrive at an ethical reflection. The images of the "freaks," with their physical deformities, may initially appear shocking, almost a punch to the gut of bourgeois sensibility, but the director manages to transform the repulsive into beauty, showing the dignity and humanity of these characters, their capacity for love, friendship, suffering, and joy, often denied them by "normal" society. The film shows how "diversity" is a socially constructed concept, a narrative fiction that serves to define the boundaries of power and conformity. The circus freaks are considered "monsters" by external society, an aberration to be exhibited or banished, but within their community, they are accepted and integrated, valued for their uniqueness, and not stigmatized. This reminds us that the perception of diversity is influenced by social and cultural norms, and that what is considered "normal" in one context can be seen as "different" in another. The freaks are victims of stigma and prejudice, that is, of a negative attribution that discriminates against and marginalizes them from society. The film shows how stigma can lead to social exclusion, discrimination, and violence, a sadly relevant lesson. Cleopatra, with her disgust and cruelty towards the freaks, embodies prejudice and the fear of the different, the superficiality of a judgment based solely on outward appearance. But Browning does not stop here; his inquiry makes us understand how prejudice can lead to dehumanization, that is, to the denial of the humanity of diverse subjects not conforming to the aesthetic canons of the dominant group. Cleopatra, by considering the freaks as monstrous creatures, deprives them of their dignity and rights, treating them as objects, with a despicable contempt that foreshadows the darkest abysses of human history. And dehumanization is a subtle and creeping process that can justify violence and discrimination, a perverse mechanism that transforms the different into an "enemy," into a "thing," depriving them of all rights. And it is with this cry of alarm that Browning leaves us, at the end of his film, a timeless warning that continues to haunt consciences, challenging the viewer to look with new eyes at their own definition of "normality" and "monstrosity."

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...