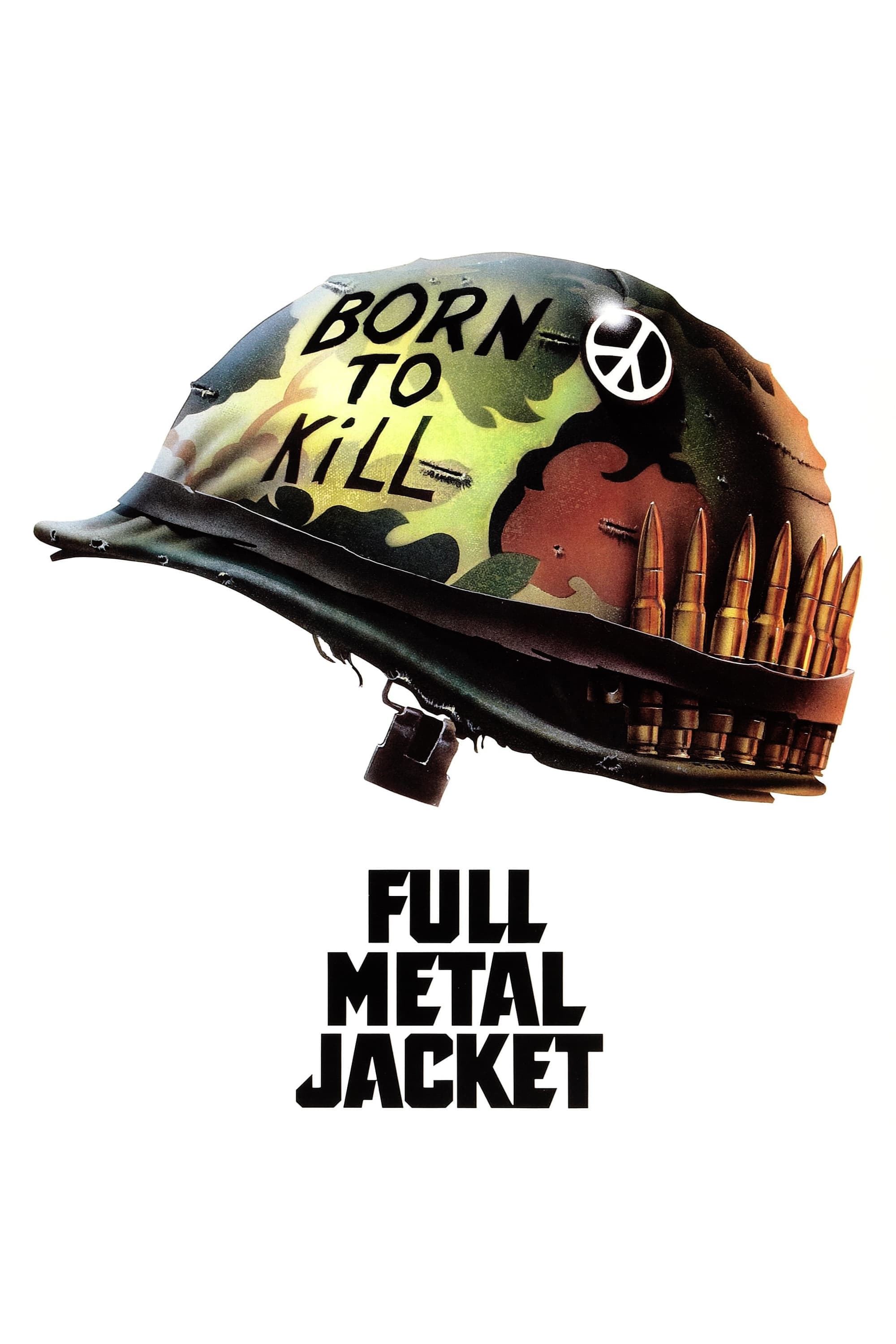

Full Metal Jacket

1987

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

After Paths of Glory and Dr. Strangelove, Stanley Kubrick once again casts his sharp gaze into the coils of war to highlight its most grotesque, most alienating elements, and with Full Metal Jacket he undertakes an immersion that transcends mere social critique to reach peaks of almost ontological nihilism.

In Paths of Glory, the fierce critique of the war machine was related to the senseless carnage imposed from above, a denunciation of strategic folly and blind obedience. In Dr. Strangelove, the theory of deterrence and the arms race were ridiculed, a distorted and satirical exploration of the atomic psychoses that afflicted the Cold War. In Full Metal Jacket, however, the analysis becomes more intimate and brutal: it is the ontological dimension of the human being in all its immense complexity that suffers the devastating effects of the conflict, a corrosion of the soul that spares no one, and the condemnation appears total, without exceptions. War is no longer an external context of horrors, but a shaping force that rewrites the psyche, destroying pre-existing identity.

Full Metal Jacket is a work rigorously divided into two parts, an almost Brechtian structure that emphasizes splitting and transformation. In the first part, we witness the arrival of recruits at a Marine training camp on Parris Island, an infernal limbo where they must endure a very tough selection before being sent to the front. This section, for its claustrophobic intensity and its almost theatrical staging of power dynamics, stands as a paradigm for all forms of indoctrination and dehumanization. Kubrick, with his unmistakable meticulousness, recreates an environment that is simultaneously hyperreal and symbolic, a true laboratory for the forging of soldiers. Every shot is calibrated to emphasize the annihilation of the individual, the reduction to a mere component of a war machine, a "full metal jacket" as the title itself suggests, which is not only a reference to protective armor, but to the cold objectification of an existence.

In the second part, we follow those same recruits into the battle theater in Vietnam, an urban landscape devastated by war in Hue, recreated with maniacal attention to detail in London's Docklands, where Kubrick demanded the demolition and reconstruction of entire neighborhoods to achieve the right desolation. It is a long journey in which they will lose innocence and humanity, a destructive odyssey that unfolds between the banality of evil and the purest horror. The narrative lucidly exposes the temporal progression of this change, the gradual crumbling of psychological barriers, subtly revealing the latent human bestiality in each of the characters involved. There is no epic heroism, only a distressing progression towards alienation. If in Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979) horror is a dreamlike and hallucinatory journey into the heart of moral darkness, and in Stone's Platoon (1986) war is a moral hell where the distinction between good and evil dissolves, Full Metal Jacket stands out for its cold, almost clinical, observation of the transformation process, avoiding explicit judgments to let the horror speak for itself.

Kubrick uses the redundant and deliberately one-dimensional characterization of each character to underscore their psychological drift, a kind of hyperbolic caricature that functions as an archetype. Drill Sergeant Hartman (masterfully portrayed by R. Lee Ermey, a former drill sergeant whose performance was largely improvised, convincing Kubrick to fire the initially chosen actor and grant him extensive freedom) is the prototype of the inflexible tough guy, the demiurge of a dehumanization process expressed through crude but almost poetic language in its obsessive repetitiveness, aimed at sweeping away every trace of individuality and replacing it with the collective identity of the Marine. Joker is the carefree intellectual always ready to cast irony on everything, the narrator with his dual identity ("Born to Kill" on his helmet and a peace symbol pin) who embodies the "duality of man," the conflict between intellect and the brutality necessary for survival. Private Pyle is the weak one, the most tragic symbol of those who let themselves be devastated by events, the fragile mind that collapses under the weight of bullying and violence, whose descent into madness is the inevitable outcome of a system that allows no deviations. His transformation, from a clumsy and docile figure to a murderous executioner, is the dark heart of the film, the most striking demonstration of how military training can disintegrate a soul.

Memorable scenes from this film have entered the mnemonic database of every cinema enthusiast, true totems of the collective imagination: Private Pyle's satanic grin as Joker's flashlight beam crosses his face, his gaze lost in the schizophrenia of someone who has left everything behind, an icon of pure terror and induced madness. Or, the soldiers' march amidst total devastation, a lunar landscape of rubble and desolation, to the dissonant and mocking notes of the Mickey Mouse March, which they sing in chorus with mocking resignation. This scene is a masterpiece of cognitive dissonance, a moment of chilling surrealism that synthesizes the absurdity of war and the total loss of innocence, almost a perverse parallel to the triumphant marches of more saccharine war films. Joker's mocking smile at the end, as he walks through the flames of a devastated city, is the epilogue of an initiation into violence that has annihilated every remnant of humanity, leaving only raw survival.

A long, harrowing cry against all war is what Kubrick entrusts to the images of this film, a distressing reflection of men stripped of all human connotation, alienated from every essence of humanity, reduced to empty fighting machines in an absurd and remote war. Full Metal Jacket is not just a film about the Vietnam War, but a universal meditation on the human condition in the face of institutionalized violence, a work that, with its relentless lucidity and detached style, forces us to confront the darkest part of our nature, that which we are willing to sacrifice on the altar of conflict. It is a bitter and hopeless warning, a visual testament that echoes Kubrick's ability to delve into the depths of the soul, revealing the monster that lurks, dormant or awakened, within each of us.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...