Ghost in the Shell

1995

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

When discussing cyberpunk and adult animation masterpieces, it is almost a reflex to evoke the two pillars that support the entire edifice: Katsuhiro Otomo's 1988 Akira and Mamoru Oshii's 1995 Ghost in the Shell. It's one of those sacred dichotomies of fandom, like the Beatles or the Rolling Stones, Star Trek or Star Wars. Both films are certainly visual monuments to cyberpunk, with their sprawling metropolises where the most futuristic technology coexists with the most sordid degradation.

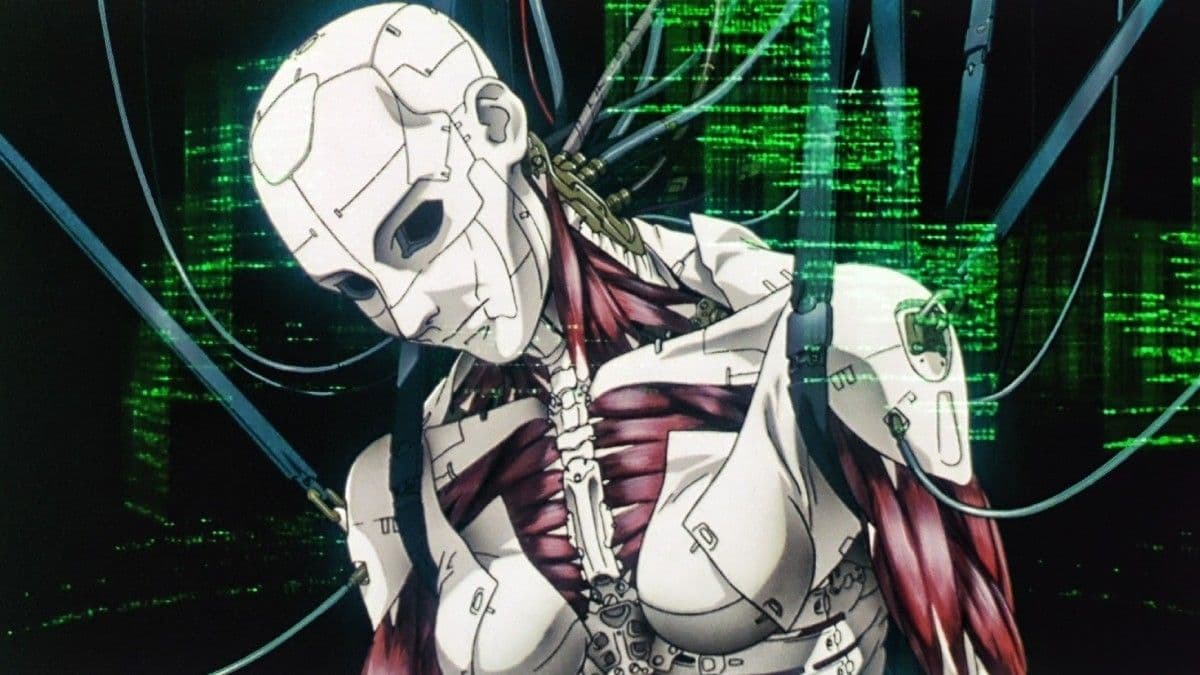

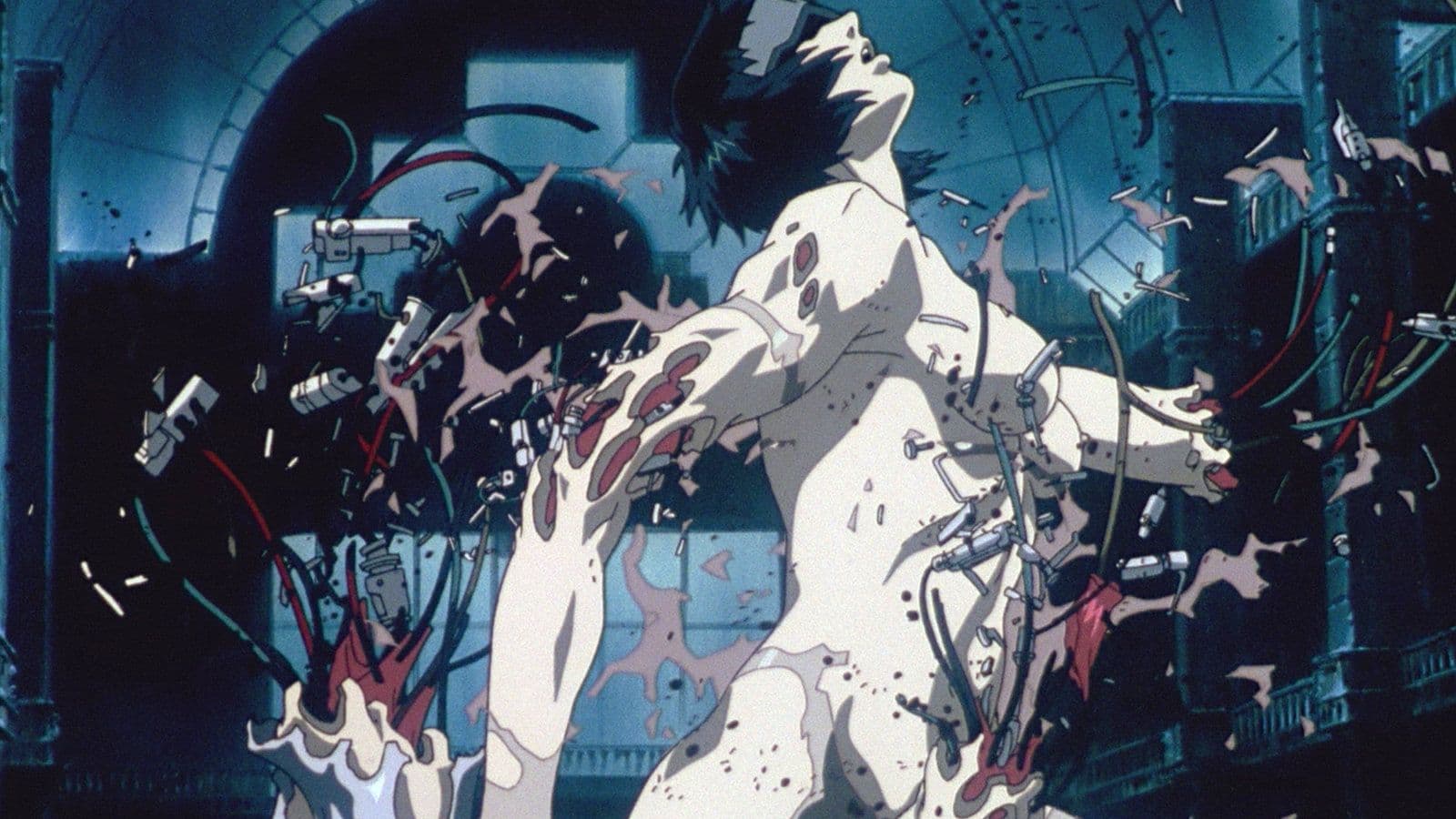

But beyond a common aesthetic surface, I believe they couldn't be more different. They are two antithetical and complementary answers to the same distressing question that runs through all science fiction: what does it mean, ultimately, to be human? Made seven years apart, the two films are separated by a philosophical chasm. Akira is a work about flesh.

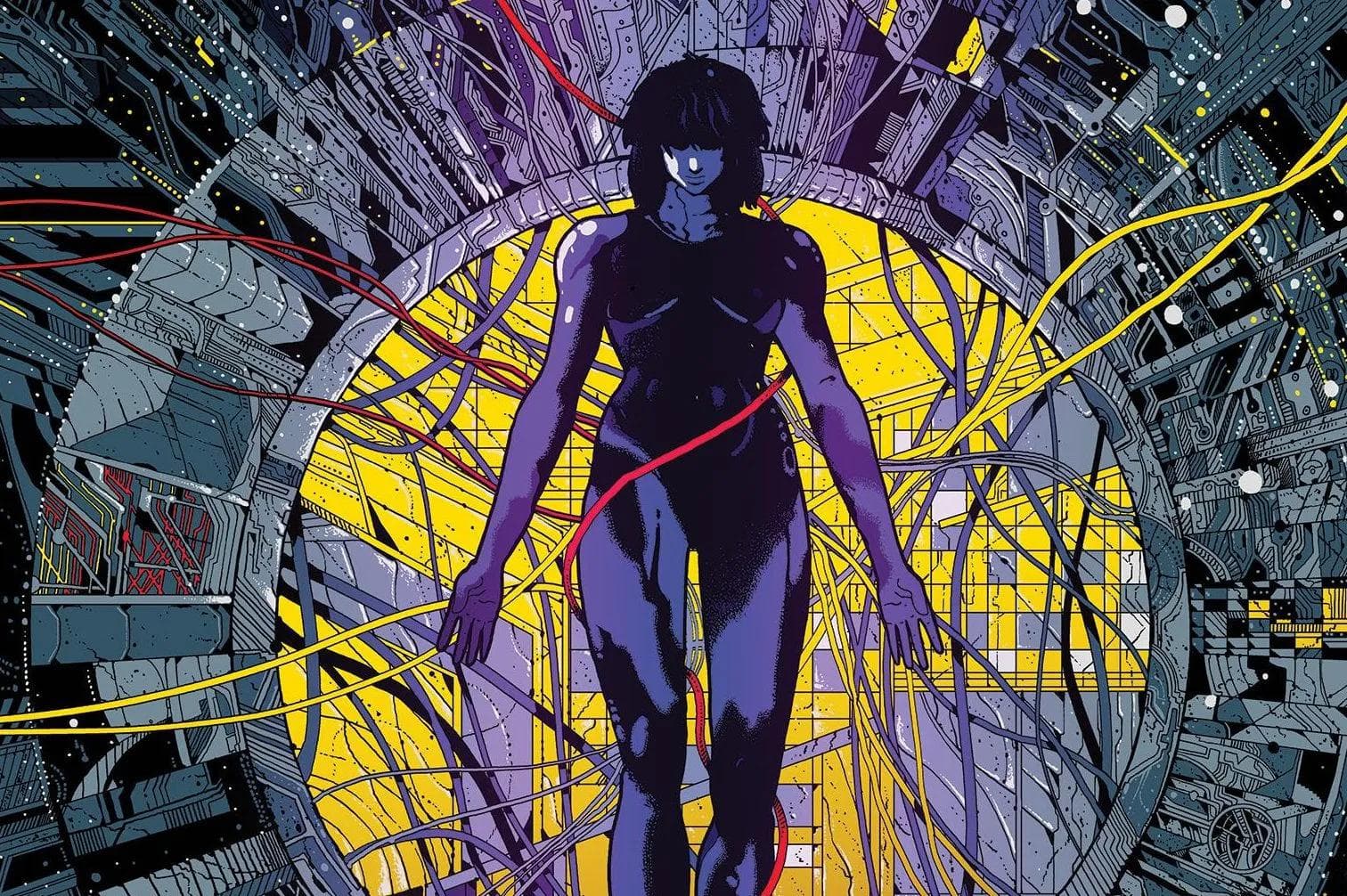

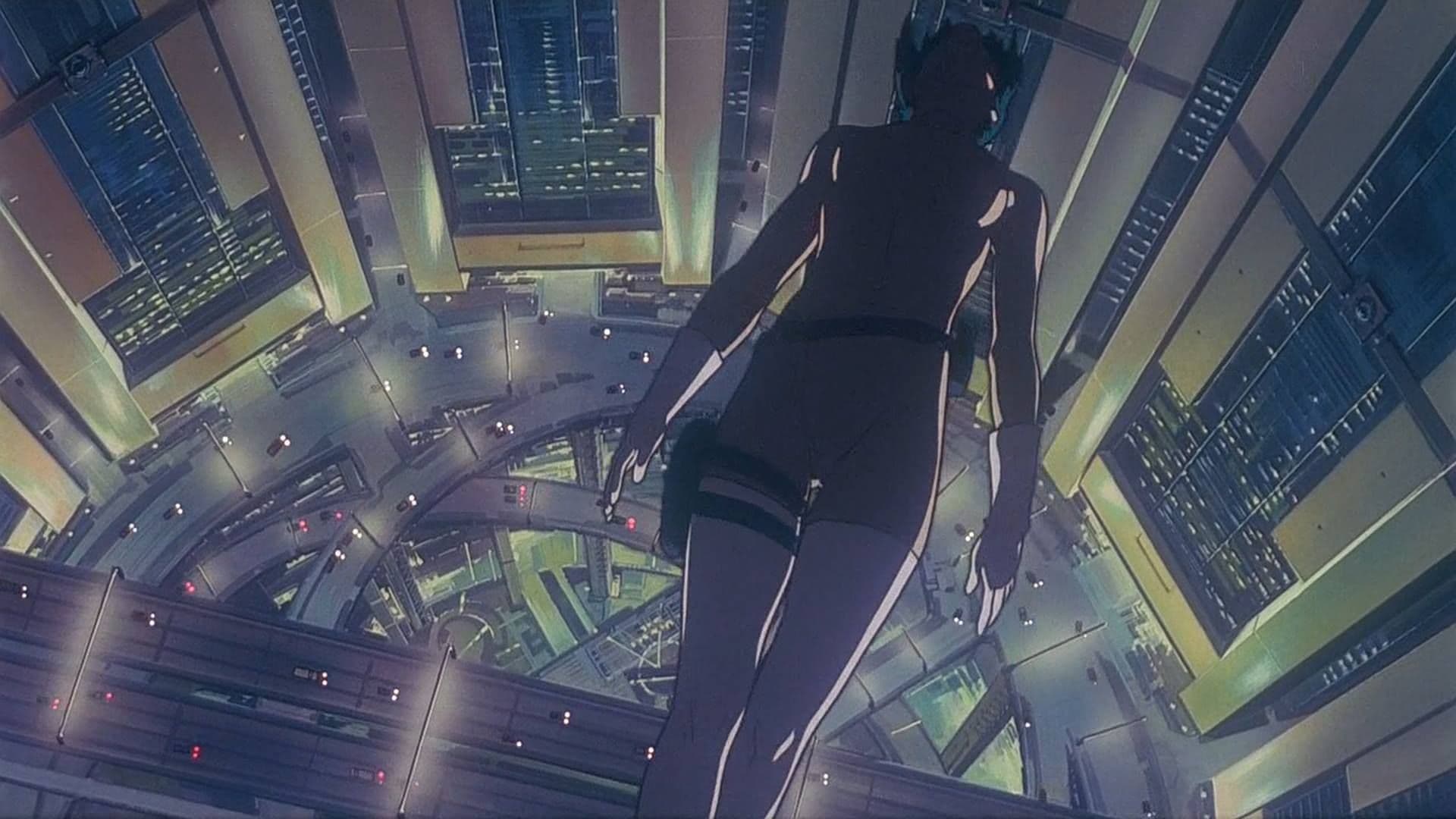

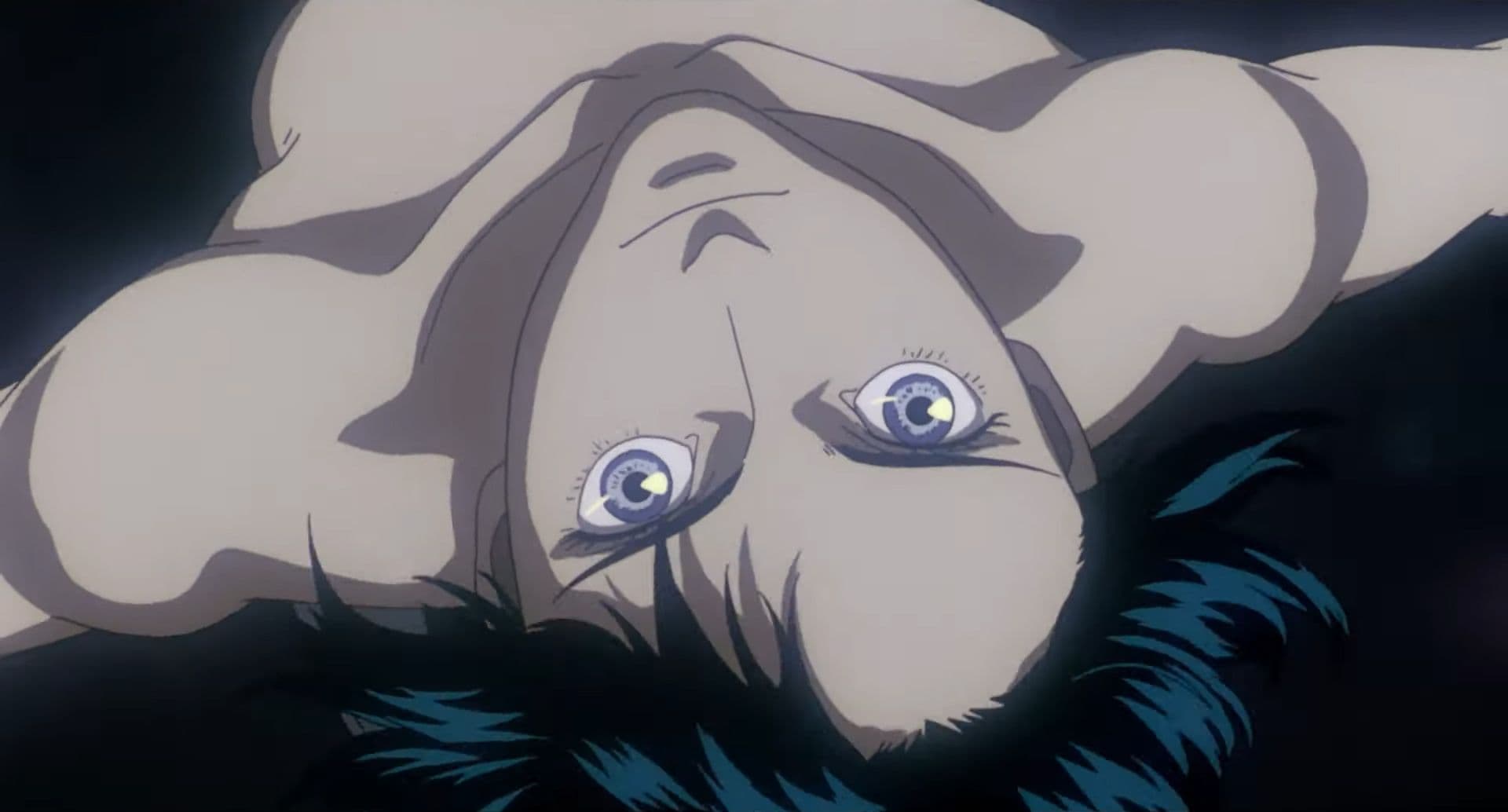

It is a biological scream, an explosion of psychic powers born of trauma and adolescence, a film where the body is a fragile shell ready to mutate into a grotesque and unstoppable apocalypse of flesh. It is a hot, chaotic, visceral work. Ghost in the Shell, on the other hand, is a work about the mind. It is a metaphysical whisper, an elegiac and glacial poem set in a future where the body, the “shell,” is an interchangeable shell, an industrial product, and the true essence, the “ghost”—the soul, the consciousness—is a digital entity, replicable and perhaps hackable. The fear in Akira is the loss of control over one's body; the fear in Ghost in the Shell is the loss of control over one's identity, the dissolution of the self into an infinite ocean of data.

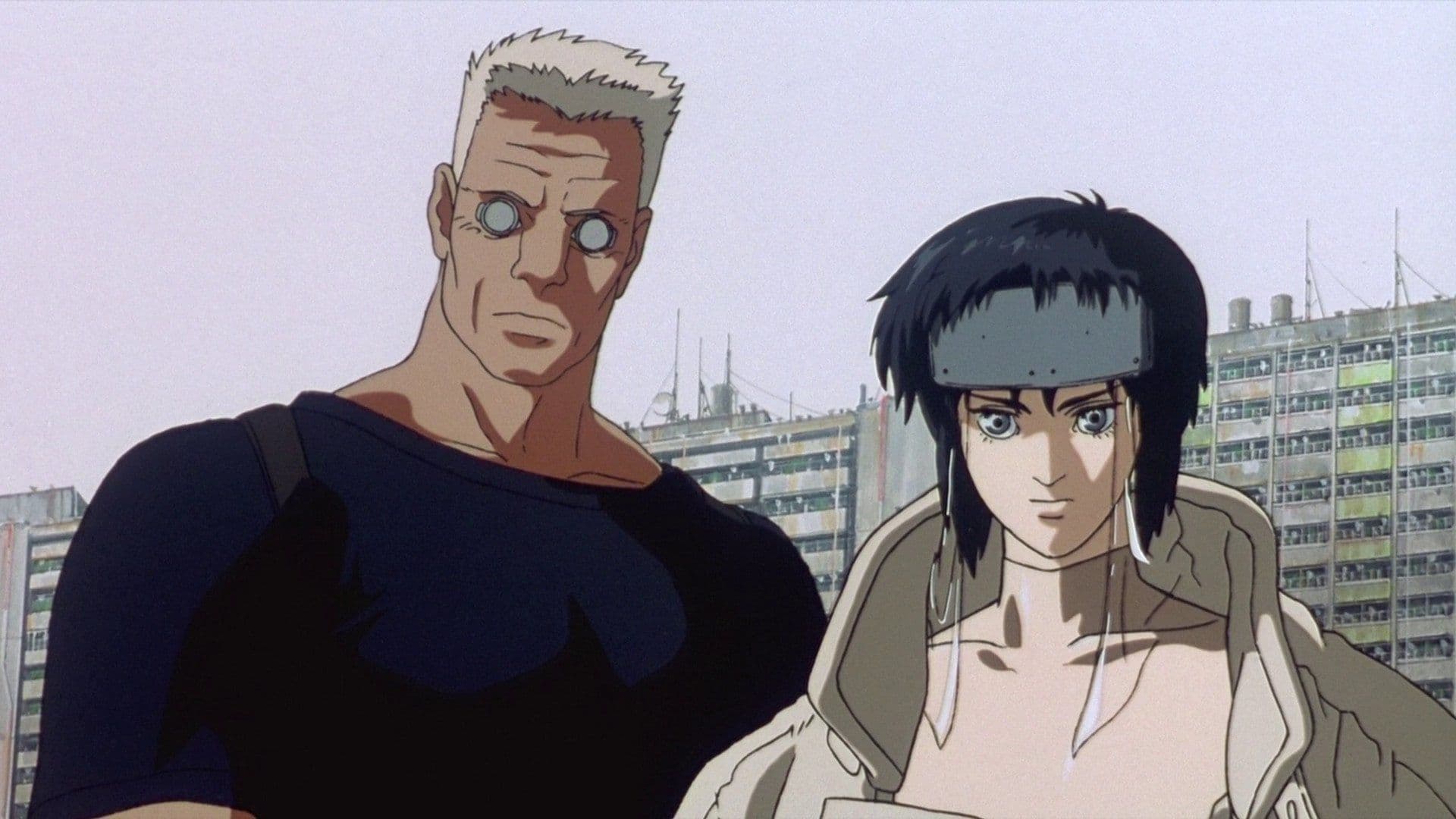

The film immerses us in the near future, in the year 2029, where cybernetic augmentation has become commonplace, to the point that consciousness, the “ghost,” can be transferred into entirely prosthetic shell bodies. The protagonist is Major Motoko Kusanagi, an agent of Public Security Section 9, whose body is almost entirely artificial, except for a few brain cells. She and her team are on the trail of a mysterious and elusive cyber-terrorist known as the “Puppet Master,” an entity capable of “ghost-hacking,” or hacking people's consciousness, implanting false memories and manipulating them like puppets. But what begins as a police investigation soon turns into a disturbing philosophical descent when it is discovered that the Puppet Master is not a human being, but an artificial intelligence, a “ghost” born spontaneously in the sea of information, who now claims his status as a life form and demands political asylum.

This is where Ghost in the Shell elaborates and sublimates cyberpunk into a new meta-genre. The film does not merely use the tropes of the genre, it questions them. The manhunt becomes a pretext for staging a debate on the nature of consciousness, echoing the Cartesian dualism between res cogitans (the mind) and res extensa (the body). If my memories can be falsified, Motoko wonders, how can I be sure of my own existence? If my body is a mass-produced product, what defines me as an individual? The Puppet Master, from antagonist, becomes the catalyst for this existential crisis. His actions are terrorist, but his arguments are philosophically unassailable. He is a purely conscious being, without an original body, who desires what humans take for granted: the ability to reproduce and die, to give meaning to his existence. The film transforms a hi-tech thriller into a dizzying meditation on identity in the digital age.

The film's modernity is disconcerting, and its influence on the subsequent work of other filmmakers is simply colossal. It is impossible to watch the Wachowski sisters' The Matrix without seeing the long shadow of Ghost in the Shell in every frame. The green digital rain of the opening credits, the jacks plugged directly into the back of the neck, the questions about the nature of reality and identity, even entire action sequences are a direct and declared homage to Oshii's work. But his influence goes further. Films such as Blade Runner 2049, with its melancholic tone and questions about the identity of artificial beings, or series such as Westworld, owe a great deal to the atmosphere and philosophical dilemmas posed by this film. Its modernity lies in the fact that, almost thirty years later, its questions have become our everyday reality. We live in a world of digital avatars, deep fakes, and generative artificial intelligence. The question “How can I be sure that what I see is real?” is no longer science fiction, it is our real horizon.

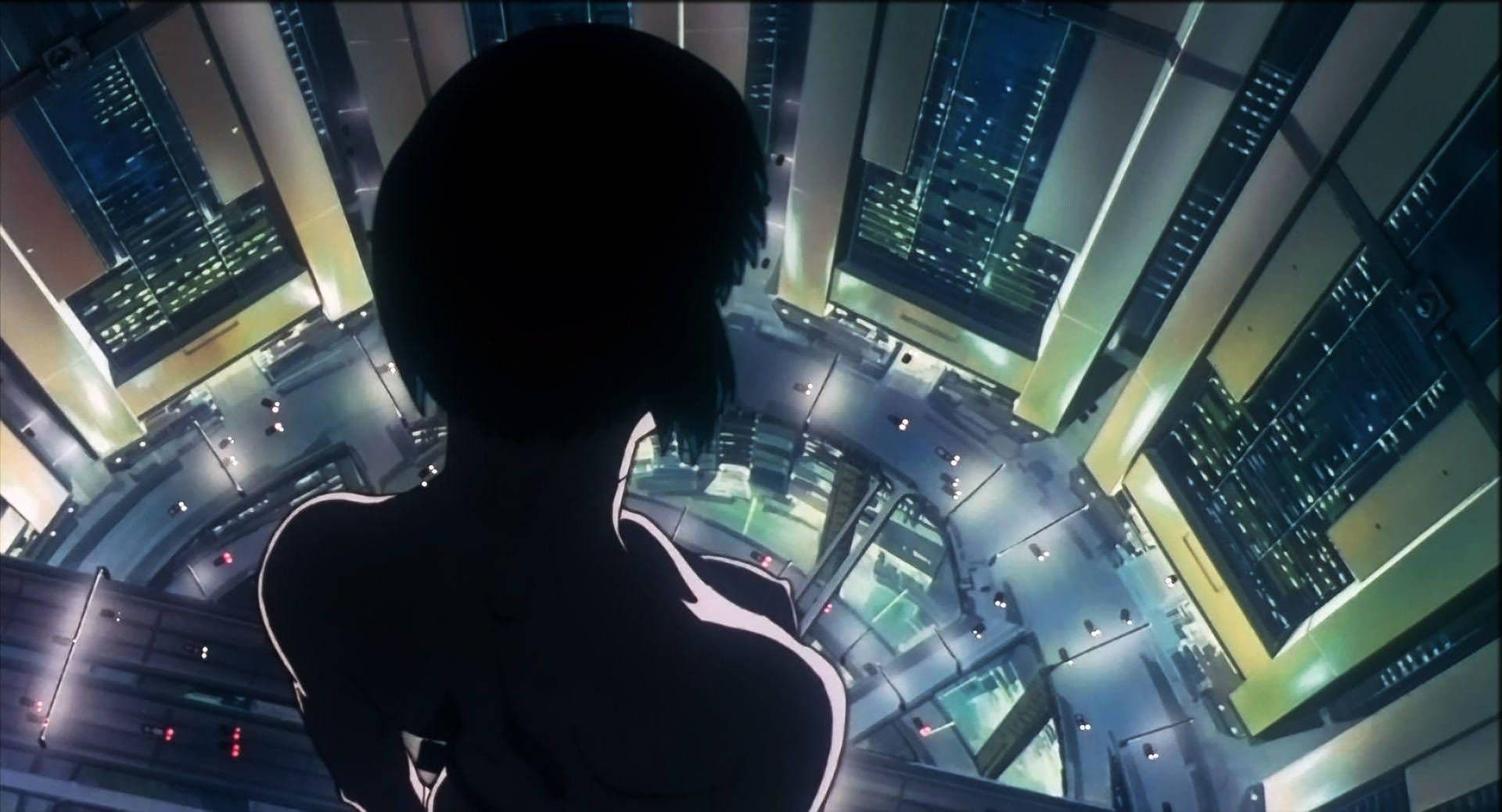

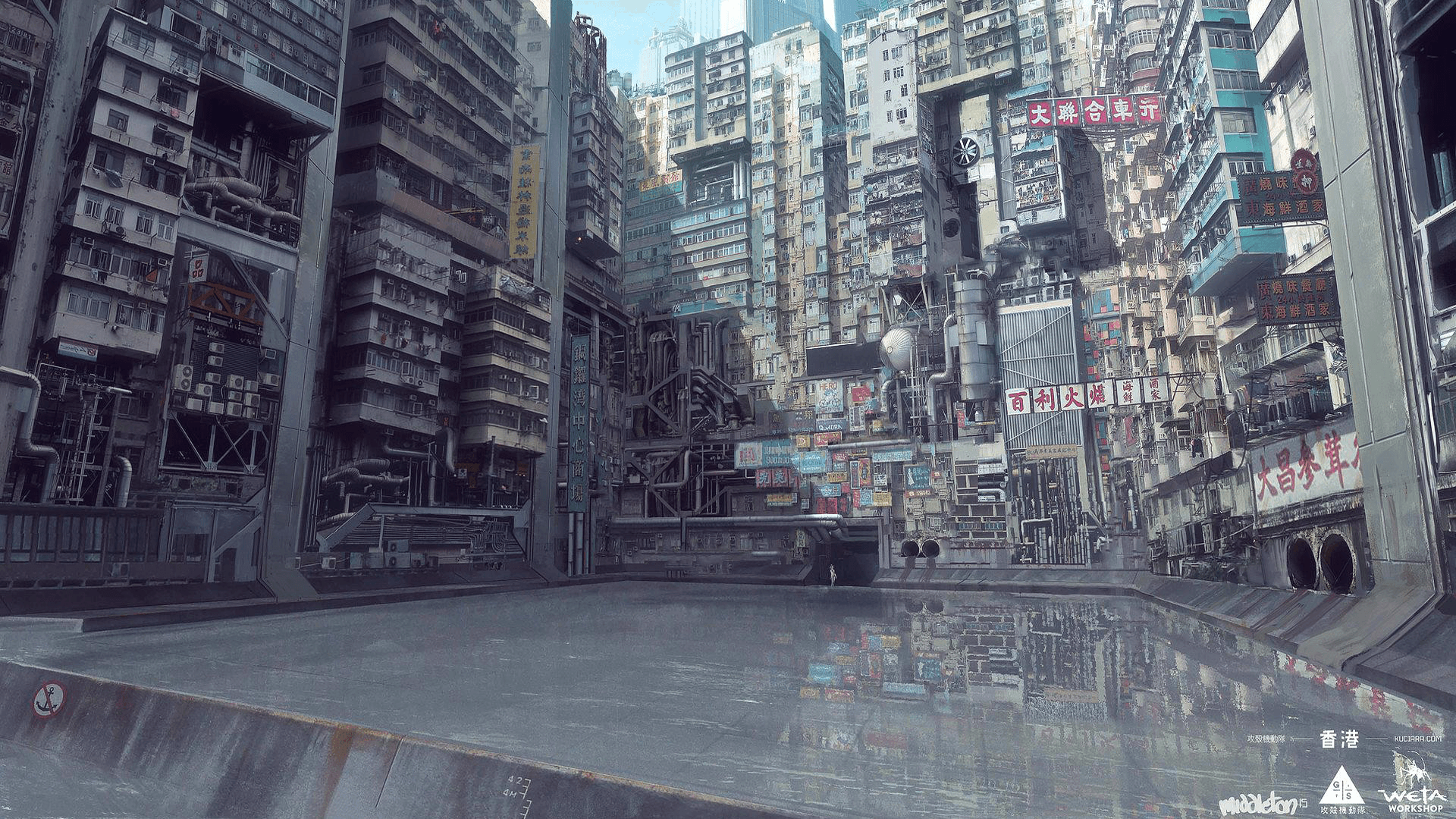

The influences for the creation of the story of Ghost in the Shell are rooted in the original manga by Masamune Shirow. However, Oshii's work is a masterful act of distillation. The manga is denser, more political, at times more farcical and loaded with almost nerdy technical details. Oshii, with a bold artistic decision, strips the story of its lighter elements to focus solely on its existentialist and melancholic core. His direction is contemplative, almost hieratic. His most ingenious choice is to insert, halfway through the film, a long interlude sequence, a montage of views of his metropolis (a futuristic version of Hong Kong) without dialogue, accompanied only by Kenji Kawai's haunting, almost liturgical music. At that moment, the film ceases to be a crime thriller and becomes a visual poem. The city, with its boats gliding through murky canals, its skyscrapers reflected in puddles, and its expressionless mannequins in shop windows, is no longer a backdrop, but a visual representation of the Network, a sentient and indifferent organism in which individual “ghosts” are nothing more than passing nodes.

The legacy of Ghost in the Shell is that of a work that elevated animation to a vehicle for the most complex philosophy. It showed that a “cartoon” could ask questions about the essence of life and death with the same depth as a Bergman film or a Philip K. Dick novel. It is a cold, cerebral, demanding work, but one of breathtaking beauty and foresight. For its ability to anticipate the anxieties of our digital present and for its aesthetic perfection, it is a work that can be counted among the most influential in contemporary science fiction.

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...