Gilda

1946

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

The language of cinema is essentially made of bodies and flesh, and then of words and gestures: it is an expressive code that originates from the human body to branch out in a thousand hermeneutic directions, capable of transforming physicality into a vector of profound meaning, a semiotics of presence that transcends mere storytelling to become pure expression of emotions, desires, unresolved conflicts. In this sense, the camera does not merely record, but frames, enhances, fragments, and recomposes the body, making it the epicenter of every drama.

Gilda is perhaps the exemplary demonstration of this thesis, elevating the concept to an almost metaphysical art form.

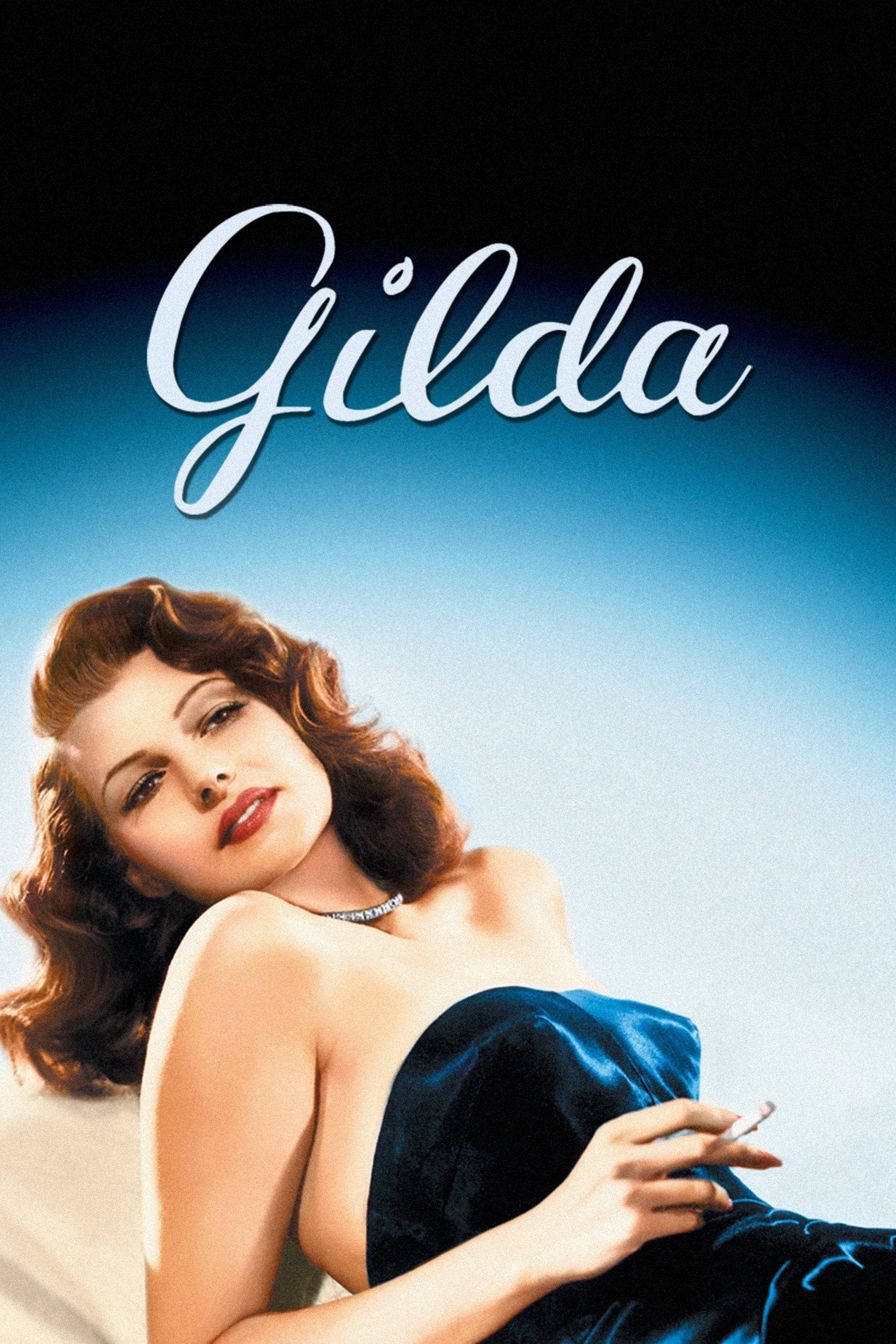

Indeed, the film expresses its message through Rita Hayworth's body and gestures, forging an iconography that has survived time and the changes of the Seventh Art, so much so that it transcends its own era to become rooted in the collective imagination as a symbol of the most dangerous and magnetic sensuality. Her stage presence, also the result of her background as a dancer, lends every movement a feline grace, a fluidity that is never mere exhibition, but always an expression of inner turmoil. The flaming red of her hair, almost a chromatic cry in a world often monochromatic like that of classic noir, became a trademark, an assertion of vitality and danger.

The character of Gilda, an archetype of the femme fatale, essentially acquires semantic significance, configuring herself as the narrative and iconographic core of the work. She is not merely a figure who acts upon the plot, but the plot itself unfolds around her enigmatic nature, her power of attraction and repulsion. Gilda is not only the temptress who leads man to ruin, but is also, in a more subtle analysis, a figure trapped by her own charm and the masculine dynamics that surround her. Her vulnerability shines through beneath the layer of seduction, making her a far more complex character than many of her noir counterparts, who often embodied a more one-dimensional wickedness.

Based on the eponymous story by E. A. Ellington and brought to the big screen by Charles Vidor — an often underrated director, yet skilled at directing actors and creating atmospheres charged with sexual and psychological tension — the film achieved enormous planetary success. Its strength did not lie solely in its intriguing story, but in its visual and thematic audacity which, despite operating under the strictures of the Hays Code, managed to communicate a surprisingly explicit subtext of provocation and sexual ambiguity.

The story is set in Buenos Aires in 1945, an atypical setting for classic noir, which usually favored gritty and disillusioned American metropolises. Here, the Argentinian capital becomes an exotic crossroads of destinies, a gilded limbo where moral rules seem more fluid and the shadow of the past looms powerfully. Johnny, a down-on-his-luck gambler with a cheating habit, is the embodiment of the disillusioned cynicism typical of the noir hero. Caught cheating in a Casino, his life takes an unexpected turn when he becomes the right-hand man of the owner Ballin Mundson, who appoints him head of security for the establishment. This relationship between the two men is immediately imbued with an ambiguous and almost palpable tension, a dynamic of power and loyalty that some critics have interpreted as a veiled but powerful homoerotic subtext, in which Gilda becomes the catalyst, or even the object of exchange, of their complex and unhealthy devotion.

Some time later, Ballin returns from a vacation accompanied by an alluring young woman he has married. Between Johnny and Gilda, Ballin's wife, there is something electric, a kind of attraction and repulsion that originates in their shared past, having been protagonists of a love story that ended abruptly. This marks the beginning of a shadowy triangle that will lead the three to contend with a sort of equation with elusive and unsolvable variables, a true psychological game of mirrors where love, hate, jealousy, and the desire for control merge into a self-destructive vortex. Vidor's direction enhances this claustrophobic ballet of emotions, often trapping the characters in close-ups and shots that underscore their isolation and mutual obsession.

Many scenes make this film a cornerstone of the noir genre, but perhaps the one ingrained in the imagination of every film lover, immortalized and celebrated ad nauseam, is the one where Gilda, with fluid and immanent sensuality, sings “Put The Blame on Mame” delightfully winking at the enraptured patrons. This sequence, despite having been heavily censored in its final version — it is said that the original choreography was far more provocative, with Rita Hayworth supposed to remove her bra, later reduced to merely taking off a glove — remains a culmination of cinematic mastery. It is not a mere performance, but an act of defiance, a performance of rebellion in which Gilda reclaims her body and sexuality to provoke, seek revenge, and assert her existence beyond masculine definitions. The symbolic removal of the glove becomes an act of psychological undressing, an exposure of her tormented soul beneath the veneer of seduction. It has made this film an archetype of the noir genre, but also a symbol of the complex relationship between a star's constructed image, her art, and her own life, as demonstrated by the tragic fate of Rita Hayworth, often trapped in the myth of the "love goddess" that Gilda had so powerfully helped to create. The film is not just a classic, it is a monument to the ambiguity and iconic power of cinema, a lesson in how a body and a glove can tell more than a thousand words.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...