Great Expectations

1946

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

An extraordinary cinematic adaptation of Dickens' novel, this Lean film is appreciated for the polished quality of its cinematography, its meticulous historical reconstruction, and its acute insight into capturing the Dickensian lesson. It is no coincidence that the film is still considered a cornerstone of British cinema, a striking example of how literature can flourish, rather than wither, in its transfer to the big screen. The "polished quality" is not merely an aesthetic matter: Guy Green's black-and-white cinematography, imbued with an almost painterly lyricism, elevates the fog of the Kent marshes and the smoke of London streets into narrative and psychological elements. Every shadow, every chiaroscuro, especially in sequences set in the decrepit Satis House or along the river wharves where ambiguous figures stir, seems to spring directly from Dickens' gothic and vivid descriptions, creating a dense, almost palpable atmosphere that captivates the reader's breath as much as the viewer's. This visual mastery, while not indulging in expressionistic excesses, borders on the poetics of an Orson Welles or a Carol Reed, demonstrating how Lean could bend light and composition to serve the narrative and the characters' subconscious.

Lean proves sensitive to his country's literary tradition and offers an insightful and compelling overview of Pip's story of ascent. His fidelity to the text is not slavish, but translates into a profound understanding of the work's spirit, a rare empathy that allows him to distill the Dickensian essence without contrivance. Pip's ascent, not a simple parable of "growth" but a winding journey of coming-of-age and disillusionment, is paced with an impeccable rhythm, almost like the progression of a filmed Bildungsroman. From humble origins, poverty, and the orphanage, Pip follows the human arc of social resurgence through the help of a mysterious benefactor. It is a journey that questions the very foundations of meritocracy and social mobility in Victorian England, revealing how fragile expectations based on promises and not on reality can be. Pip's destiny, initially unaware and naive, is emblematic of how hopes, when they are "great" and not anchored to solid values, can turn out to be dangerous illusions.

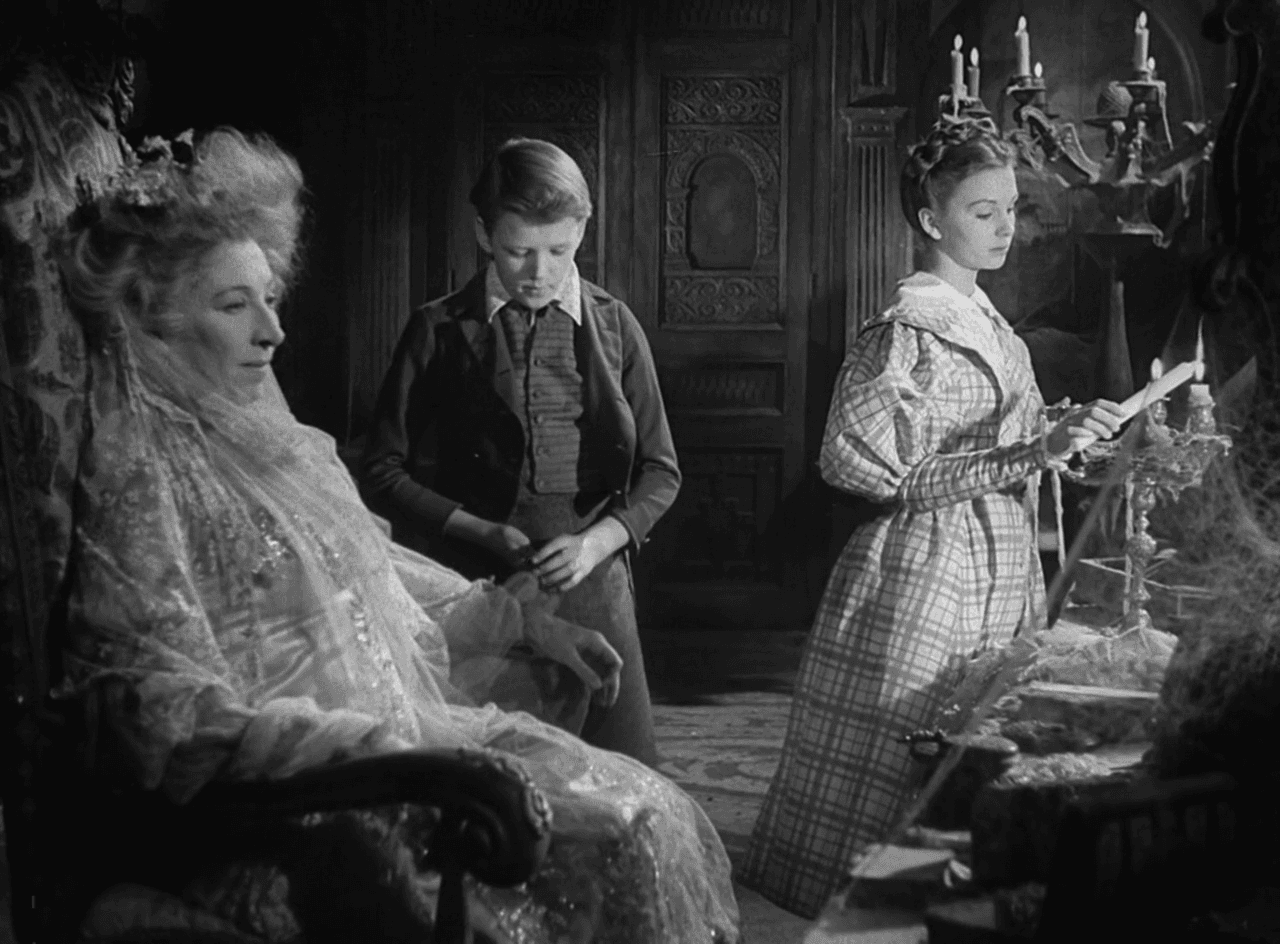

From schools will emerge a gentleman of noble bearing, capable of illustrious achievements: quickly getting rich, frequenting the salons of the noble elite, impressing girls from good families. But it is precisely in this apparent ascent that the true tragedy and the most acute moral lesson lie. Pip's entry into the vortex of London society, magnificently rendered in scenes showing the hypocrisy of his new "peers" and the sophisticated amorality of figures like the lawyer Jaggers, highlights the superficiality and emptiness of purely material ambitions. The "gentility" acquired by Pip is a thin veneer that hides the abandonment of his true roots and the humiliation of those who, like Joe Gargery, had loved and supported him unreservedly. And then there is Estella, an enigmatic and tragic figure, molded by Miss Havisham's icy revenge. The latter, an icon of Dickensian grotesquerie, is portrayed by Lean with a visual effectiveness that goes beyond a mere caricature: she is the living symbol of a past frozen in pain and madness, contaminating the present and destroying the future of others. Pip's love for Estella, an unattainable and painful love, becomes the perfect metaphor for his aspiration to something intrinsically corrupt and irredeemable, an illusion as splendid as it is deadly. Estella's coldness is not malice, but the result of an education in cruelty, which renders her incapable of true affection, a beautiful but heartless doll.

When he falls in love with his benefactor's daughter, he will discover that this benefactor is none other than a murderer in prison. This is the core of the revelation, the moment when Pip's "great expectations" crumble, bringing to light the uncomfortable truth and the dark root of his fortune. The figure of Abel Magwitch, the convict who becomes his benefactor, is handled by Lean with a sensitivity that enhances his complexity: he is not simply a criminal, but a man capable of deep loyalty and affection, whose generosity, though coming from a place of darkness, is infinitely purer than the hypocrisies of the world Pip had so yearned for. The discovery of Magwitch's identity is a plot twist that not only overturns the protagonist's fate but forces him into deep moral reflection, to reconsider his place in the world and the true meaning of nobility of spirit. This passage, masterfully orchestrated, marks Pip's true growth, an inner growth, made of humility and acceptance, far more significant than his social ascent.

Lean does not interpret Dickens; he simply imprints him onto film and offers him to us with a stylistic purity that fascinates. This seemingly simple statement hides the essence of Lean's genius as an adapter. There is no authorial imposition, no attempt to modernize or personally reinterpret the classic. Rather, there is an almost maniacal dedication to the faithful transposition of the Dickensian spirit, tone, and atmosphere through a cinematic language of rare precision. Every shot, every transition, every editing choice (Lean was also a talented editor) is aimed at serving the narrative and characters with maximum clarity and emotional impact. His "stylistic purity" is not minimalism, but such an absolute mastery of technical means as to render them invisible, allowing the story to unfold with irresistible fluidity and power. This approach has set a benchmark for subsequent literary adaptations, demonstrating that the greatness of a work lies not so much in innovative interpretation as in the ability to make it resonate in its most authentic and heartfelt form.

A film that will not fail to move, but which above all invites deep reflection on the universal themes of ambition, unrequited love, redemption, and the true value of identity. It is a timeless classic that, decades later, continues to dialogue with the present, offering a lesson in cinema and life that remains etched in memory.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...