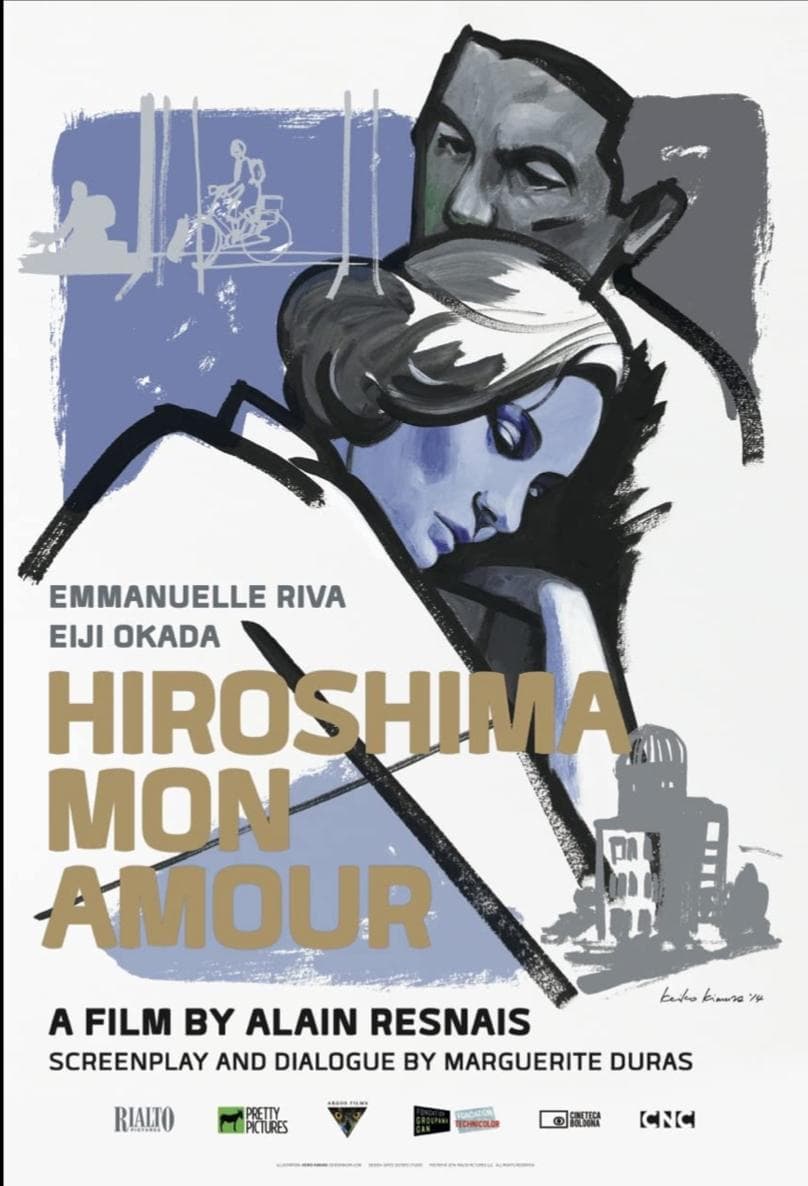

Hiroshima Mon Amour

1959

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A rare and precious stone in the treasure chest of French cinema. Not only for its stony beauty and emotional impact, but for the intellectual and stylistic audacity that redefined the frontiers of cinematic storytelling.

Alain Resnais directs with poetic craftsmanship a story that touches on memories and fragments of past lives, rising to a profound meditation on the inexorable passage of time, on the indelible scar of trauma, and on the ambiguous nature of memory itself. His sensitivity, already acute in documentaries like Night and Fog, which explored the horror of the Shoah with lucid and harrowing honesty, here shifts to a more intimate and psychological plane, while still retaining a universal breadth. Resnais, often associated with the Nouvelle Vague but more accurately placed within the Rive Gauche group – alongside filmmakers like Agnès Varda and Chris Marker, all characterized by a more literary, philosophical approach and a profound historical consciousness – forges with Hiroshima Mon Amour a radically new visual and narrative language.

A woman is sent to film a pacifist movie in Hiroshima; she meets a Japanese man with whom she spends the night. The encounter becomes an opportunity to awaken a dormant old love for a German soldier during World War II. The narrative, co-written by the visionary Marguerite Duras – whose lyrical and fragmented prose finds its perfect cinematic transposition here – unfolds in a continuous osmosis between past and present, between the here and now of Hiroshima and the painful memory of Nevers, the French city where the young woman had lived her tragic love. The Japanese city is not just a backdrop, but a living entity, a silent character whose story of annihilation and rebirth is reflected in the tormented psyche of the protagonist. Her body, her gestures, her whispers, become the catalyst for an almost Proustian analysis of involuntary memory, but with a post-atomic urgency that makes it searing.

A film that makes human memory and lived emotions a pillar supporting its magnificent lyricism. Memory here is not a simple archive of events, but a battlefield, a fluid and deceptive entity, capable of concealing and revealing, of torturing and liberating. Resnais and Duras explore the paradoxical necessity of forgetting to survive too great a pain, and at the same time the impossibility of truly doing so, because the past, like a ghost, continues to re-emerge, distorted, yet powerfully present. This dialogue between necessary oblivion and ineluctable remembrance is the pulsing heart of the work. The film is interwoven with a non-linear dialogue, made of obsessive repetitions, truncated phrases, a stream of consciousness that reflects the very nature of memory, never clear and sequential, but always associative, emotional, elusive.

One scene above all: the magnificent monologue the woman recites almost in a dream, embraced by her lover, while moving images of Hiroshima flow by, a sinuous creature accompanying the woman's whisper: “Like you, I too tried to fight with all my might against forgetfulness, and like you, I forgot. Like you, I desired to have an inconsolable memory. A memory made of shadow and stone. I fought alone, violently, every day, against the horror of no longer being able to understand the reason for this memory. Like you, I forgot. Why deny the evident necessity of remembrance. Listen to me, I know all this will repeat: two hundred thousand dead, eighty thousand wounded in nine seconds, these figures are official, but all this will repeat. We will have ten thousand degrees on earth. Ten thousand suns, they will say, the asphalt will burn, a profound disorder will reign, an entire city will be lifted from the ground and fall back into ashes, and new vegetations will rise from the sand. Four students await a fraternal and legendary death together. The seven arms of the Ota River delta estuary empty and fill at the usual hour, more precisely at the usual hours, with fresh, fish-filled water, grayish-blue, according to the hour and the seasons. But people will no longer look along the muddy banks at the slow rising of the tide of the seven arms of the Ota River delta estuary. I meet you and I remember you. Who are you? You kill me. You do me good. How could I have known this city was made for my love? How could I have known your body fits mine? I like you, what an event. I like you... what a sudden languor. What sweetness, you cannot know. You kill me, you do me good... You kill me, you do me good. I still have time, please: devour me, deform me to horror. Why not you? Why not you in this city and in this night so similar to others, to the point of becoming unrecognizable. Please... It's crazy that you have such beautiful skin...”.

This monologue is not just an apical point of the screenplay, but a snapshot of the woman's soul, a cry of pain and desire, an admission of her vulnerability and strength. The brutal figures of the nuclear catastrophe mingle with the intimate details of the lover's body, creating an emotional short-circuit that abolishes all distance between the personal and the political, between grand history and individual drama. The scene synthesizes the film's formal audacity: the use of voice-over as an underground current of consciousness, the associative editing that superimposes documentary images of the real Hiroshima onto fragments of the Nevers memory, and the ability to transform pain into a form of melancholic and inexorable beauty. The film is a symphony of images and words that respond to and complement each other, elevating the eroticism of the encounter to a metaphor for an attempt at reconnection with the world after devastation, be it personal or collective. It is the first film to confront the unspeakable so directly and intimately, paving the way for a cinema that is not afraid to face the darkest folds of the human psyche and history. A work that, more than sixty years after its release, continues to resonate with a rare power, challenging the viewer to confront their own ghosts and the inconsolable, yet vital, weight of memory.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...