The Color of Pomegranates

1969

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Attempting to review Sergei Parajanov's The Color of Pomegranates (1969) using traditional film criticism tools is a futile endeavor, like trying to measure a dream with a ruler. This work cannot be analyzed, it must be experienced. You don't follow it, you surrender to it. It is a visual poem, a moving iconostasis, a filmic ritual that abolishes the tyranny of narrative prose to speak to us in a lost language made up of symbols, colors, and silences. It is one of those rare masterpieces that do not merely tell a story but reinvent cinema itself, forcing us to learn how to watch again.

The film sets out to tell the life story of the 18th-century Armenian poet Sayat-Nova, but it does so with disarming honesty and radicalism. Parajanov has no interest in constructing a conventional biography, a biopic with a beginning, a middle, and an end. His stated and magnificently achieved goal is to evoke the poet's inner universe, to translate the essence of his art and soul into a sequence of visions. We see scenes depicting his childhood, his first love, his retreat to a monastery, and his death, but these are not events, they are allegories. They are the stages of a spiritual journey where every object is a hieroglyph, every gesture a liturgy. Sayat-Nova's life, from childhood to death, his spiritual journey, artistic achievements, and inner conflicts are thus filtered through the prism of his own poetic sensibility, in the cultural and historical context of an Armenia that exists as a mystical rather than geographical entity. It is no coincidence that another visionary genius, Mikhail Vartanov, immediately hailed it as a revolutionary work: in a Soviet Union that imposed “socialist realism” as the only artistic doctrine, a film so blatantly formalist, symbolic, and rooted in a specific national and religious culture was an act of pure and courageous dissent.

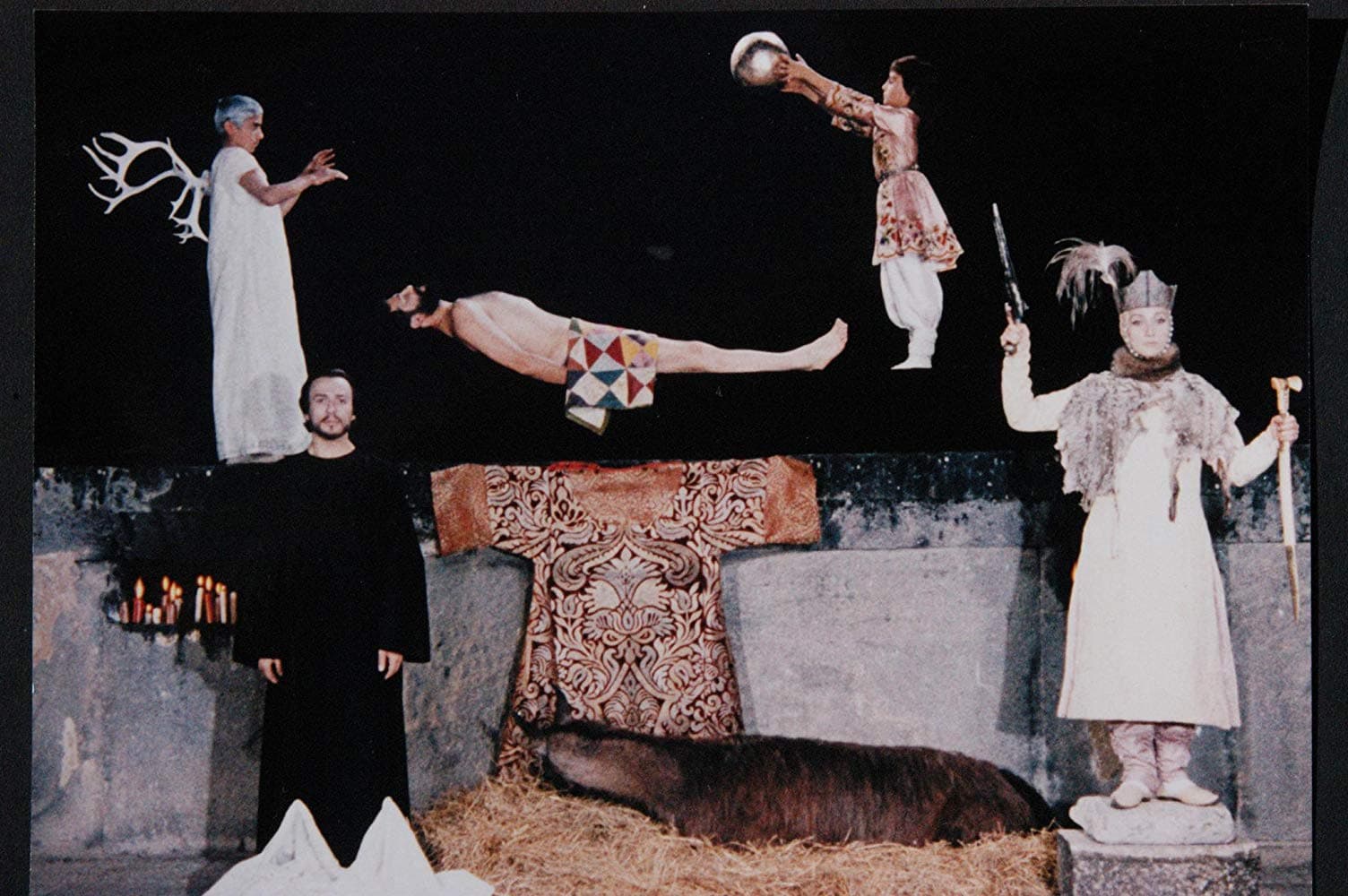

The film's aesthetic framework is its greatest triumph, a visual language that draws heavily on Russian and Armenian iconographic tradition, but contaminates it with influences that span the entire history of art. The composition is almost always frontal, the perspective is flattened, and the characters move with ritualistic slowness within a static frame. It is as if Parajanov had taken ancient Orthodox icons and Armenian illuminated manuscripts and breathed life into them. His characters are not psychological figures, they are hieratic archetypes, whose impassive faces offer themselves to the viewer's gaze like those of saints. The choice to have the same actress, the magnificent Sofiko Chiaureli, play multiple roles—the young poet, his muse, the nun—is not a quirk, but a profound poetic intuition: love, art, and faith are different faces of the same soul. Although the visual heart is Eastern, the similarities with European painting currents are striking. The theatricality and symbolic density of certain tableaux vivants are reminiscent of surrealist painting, particularly the metaphysical atmospheres of De Chirico, where everyday objects are decontextualized to take on a new and mysterious meaning. A book from which pomegranate juice bleeds, a fish pulsating on the pages, are images that speak directly to the unconscious.

This ontology based on pure image creates an unexpected bridge with other visionary works. The most fitting analogy, albeit chronologically reversed, is with Tarsem Singh's The Fall. Both films reject naturalism to construct worlds governed by a purely aesthetic logic, where each shot is an autonomous work of art and the narrative proceeds through chromatic and symbolic associations. However, if The Fall is a baroque, romantic, and narrative explosion rooted in the imagination of a single storyteller, The Color of Pomegranates is more austere, more hermetic, a ritual that draws not on individual imagination but on the collective unconscious of an entire culture. It is closer in spirit to the cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky (who in fact admired and strenuously defended Parajanov) for its ability to imbue natural elements—water, fire, earth—with an almost unbearable spiritual weight. The film does not tell the story of Sayat-Nova, it is Sayat-Nova. It is a work that does not ask to be understood, but to be contemplated, as one contemplates an ancient icon, allowing its colors, shapes, and silence to resonate within us, revealing truths that no words could ever express.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...