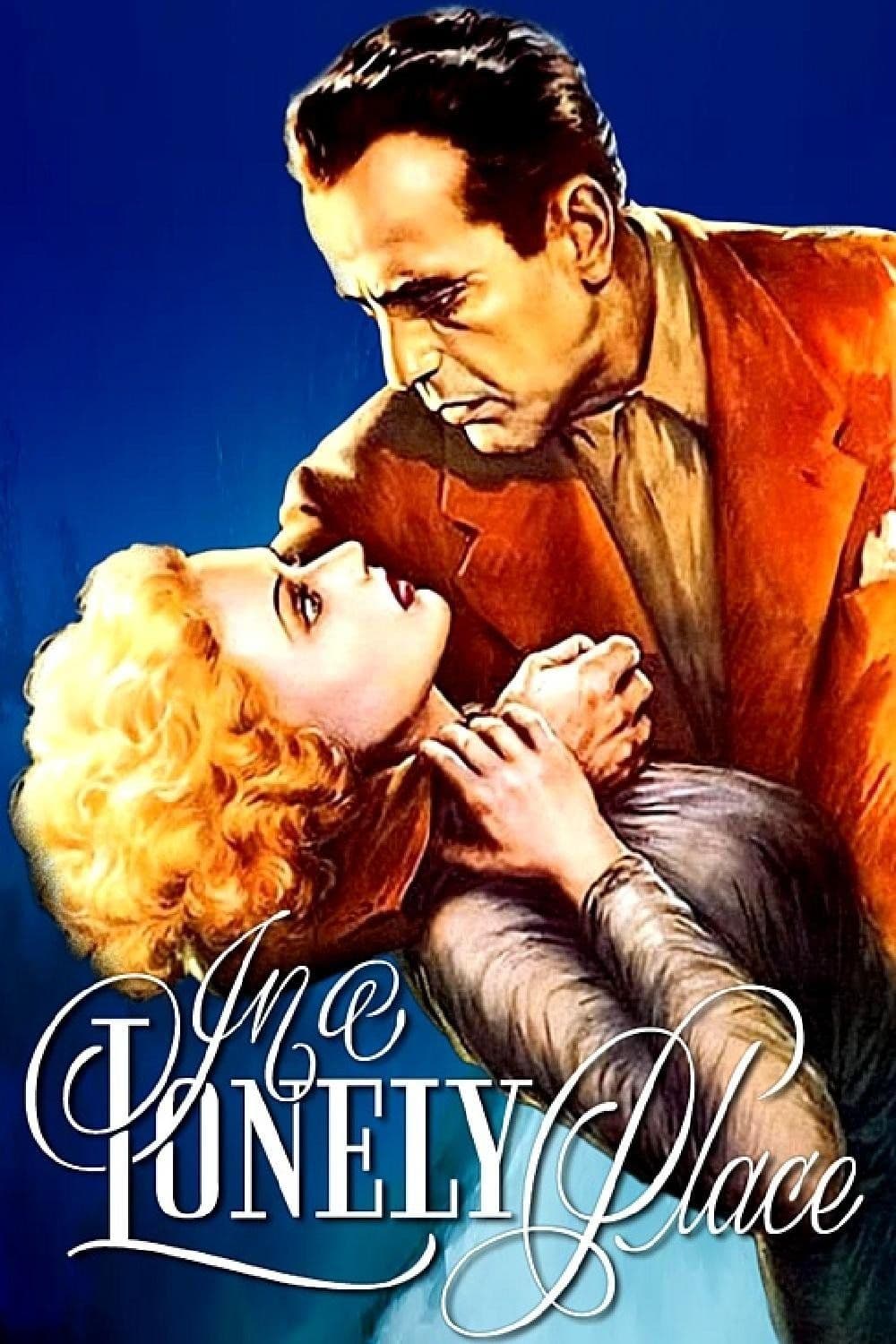

In a Lonely Place

1950

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

The film is titled “In a Lonely Place” with an evocative and powerful title, but the Italian titler, as usual, put their own spin on it, resulting in an improbable title, “The Right to Kill” (“Il Diritto d'Uccidere”). This unhappy translation, while referencing the underlying magma of violence boiling in the protagonist’s heart, betrays the subtle and poignant resonance of the original title. “In a Lonely Place” is, in fact, the perfect synthesis of the film's essence: psychological isolation, emotional desolation, the inner prison that the writer Dix Steele builds around himself and, by extension, around anyone who dares to approach him. This misalignment between authorial intent and distribution’s interpretation, unfortunately common in the history of Italian cinematography, serves as an involuntary prologue to a work that delves into the cracks of the human soul with an almost brutal clarity.

Despite this, the work is a splendid archetype of the noir genre, and at the same time, an audacious deconstruction of it. Nicholas Ray, with a master's touch, does not merely paint the typical shadows and lights of the genre but uses them to illuminate the darkest recesses of the psyche. We are not faced with a mere mystery to solve or a conspiracy to uncover; the true enigma here is the protagonist’s inner identity, the nature of his latent violence, the moral and psychological precipice on which his existence is constantly balanced. It is a noir that sheds its detective plot to become pure psychological drama, almost Freudian, where the danger does not come from the outside, but from the threat of an internal implosion.

Bogart’s performance is remarkable in the role of a violent, paranoid writer of trashy bestsellers, suspected of having killed a girl he met casually. It is perhaps his most audacious and corrosive performance, a true subversion of the icon that had made him immortal. Here, Bogart is no longer the charming cynic with a heart of gold à la Rick Blaine, nor the disillusioned but incorruptible detective à la Sam Spade. Dix Steele is a shattered figure, a man tormented by inner demons, an artist whose genius is inextricably linked to a self-destructive fury. His acting, made of turbid gazes and sudden outbursts, forced smiles and moments of chilling lucidity, conveys a sense of imminent danger, of an emotional time bomb ready to explode. A raw portrait of post-war masculinity, undermined by anxiety and loss of control.

His neighbor, in an act of apparent generosity, provides him with an alibi, momentarily pulling him out of trouble; attracted to him, she becomes his Muse and Nemesis. Laurel Gray, played by the sublime Gloria Grahame, is a key character, far more complex than the classic noir femme fatale. She is the muse who inspires Dix’s creative reawakening, but her fragility and sensitivity also make her the designated victim of his growing paranoia. Grahame, with her husky voice and melancholic eyes, perfectly embodies the vulnerability and quietly desperate strength of a woman trapped in a toxic relationship. She is not the temptress who leads the hero to ruin, but the mirror in which the hero sees his own unbearable violence reflected. Her transformation from trusting lover to terrified woman is the barometer of Dix’s descent into madness.

Nicholas Ray’s direction is truly unforgettable, creating an iconographic taxonomy of film noir with rapid tracking shots alternating with obsessive close-ups. Ray uses the camera not as a mere recording device, but as a scrutinizing, almost intrusive eye, exploring the psychological depths of the characters. The tracking shots, sometimes frantic, sometimes slow and unsettling, follow Dix’s agitated psyche, while the insistent close-ups reveal Laurel’s escalating anguish. The skillful use of chiaroscuro, the interplay of light and shadow in claustrophobic interiors, not only creates atmosphere but also reflects the protagonists’ mental state: gloom as a refuge for madness, light as a cruel revealer of truth. Ray succeeds in elevating the visual language of noir, making it the primary instrument for psychopathological analysis, an element that we will also find, albeit in different contexts, in later works such as the famous “Rebel Without a Cause.”

The film is a highly effective study of an individual teetering on a razor’s edge. Equally effective is the shift in perspective whereby we move from Bogart’s sense of entrapment to Grahame’s feeling of unease. This narrative refocusing is a stroke of genius, amplifying the sense of tragedy. Initially, the audience is invited to sympathize with Dix, to believe in his innocence, to perceive his frustration with an unjust judicial system. But as the truth of his character unfolds through his interaction with Laurel, our empathy shifts. It is no longer the fear of being convicted for a crime he did not commit that dominates, but the fear of what he is capable of doing, his inherent violence, his inability to love without destroying. The razor’s edge he walks is not one of justice, but rather one between sanity and madness, between love and destruction.

Like Rick in Casablanca, Dixon also loses badly in love, but here the man is pushed to his psychological limit, producing a searing portrait of a man torn in two. If Rick sacrifices his love for a greater good, with a nobility of spirit that elevates him to myth, Dixon Steele detonates it due to his own self-destructiveness. There is no redemption, no hope. Bogart, in this epochal performance, dismantles the archetype of the romantic hero to which he had accustomed us, revealing an anti-hero who is a prisoner of his darkest impulses. The portrait is searing because it shows the destruction of a man not by fate or an external enemy, but by the corrosive action of his own inner fragilities and violence, a conflict that slowly, deliberately tears him apart.

A tremendous conflict that permeates the viewer's soul and slowly, deliberately tears it apart, finally leading them where Ray intended: not to a catharsis, but to a profound, disquieting melancholy. The ending, devoid of easy resolutions or moral triumphs, is a profoundly powerful statement of intent. There is no discovery of the "true" killer to bring justice, but only the tragic realization of an irretrievably lost love, shattered by Dix's internal violence and Laurel's fear. It is a bitter conclusion, which rejects the genre's typical consolation and closure, leaving the viewer with a lingering sense of incompleteness, of a missed opportunity, of a life ruined not by a gunshot, but by a slow, inexorable suffocation of the soul. The Right to Kill reveals itself, ultimately, to be the right to kill love, and with it, all remaining hope.

Comments

Loading comments...