Sleeper

1973

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

An early Woody Allen directs one of his most entertaining and surreal films, a work that, fifty years after its release, continues to shine with a biting wit and visionary comedy, revealing the early mastery of an author destined to redefine the contours of American intellectual comedy. It is 1973, and Allen, drawing on his experiences as a stand-up comedian and screenwriter, as well as his initial directorial forays that had already shown a peculiar penchant for nonsense and parody (consider Take the Money and Run or Bananas), delves into the science fiction genre, not to explore its technological anxieties or existential dystopias dramatically, but to make it a launching pad for an irresistible philosophical farce.

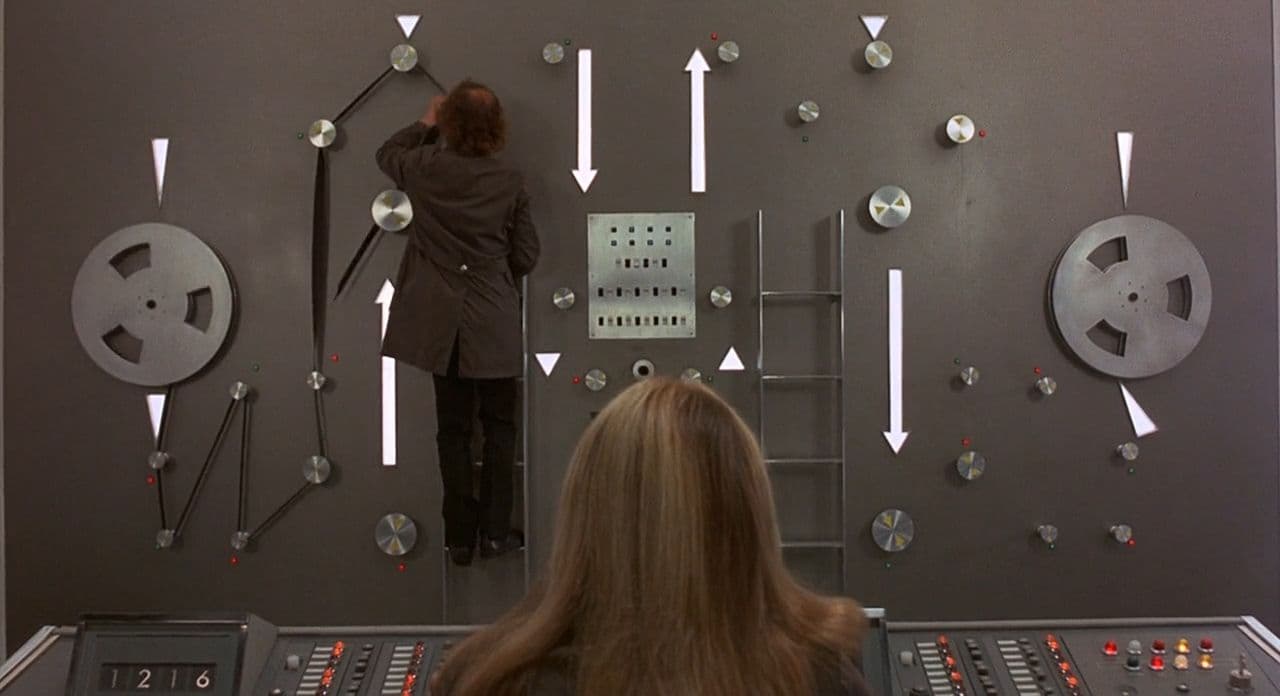

In 1973, Miles Monroe, a jazz clarinetist and owner of a macrobiotic grocery store – a detail that alone paints a hilarious portrait of a certain counterculture of the era – after being hospitalized for excruciating stomach pains, is accidentally cryogenically frozen and wakes up two hundred years later, in an improbable future governed by a totalitarian and repressive regime. The opening is a programmatic manifesto: science, instead of solving humanity's problems, complicates or ignores them with a bureaucratic indolence that anticipates the Kafkaesque. Miles finds himself catapulted into a sterile society, excessively sanitized and devoid of all authentic emotion, where conformity is law and dissent an aberration to be cured. It's a world of white, aseptic architectures that nod to the visual purity of 2001: A Space Odyssey, but reinterpreted farcically, where Kubrick's HAL 9000 is replaced by an invisible authority and spatial transcendence by daily oppression.

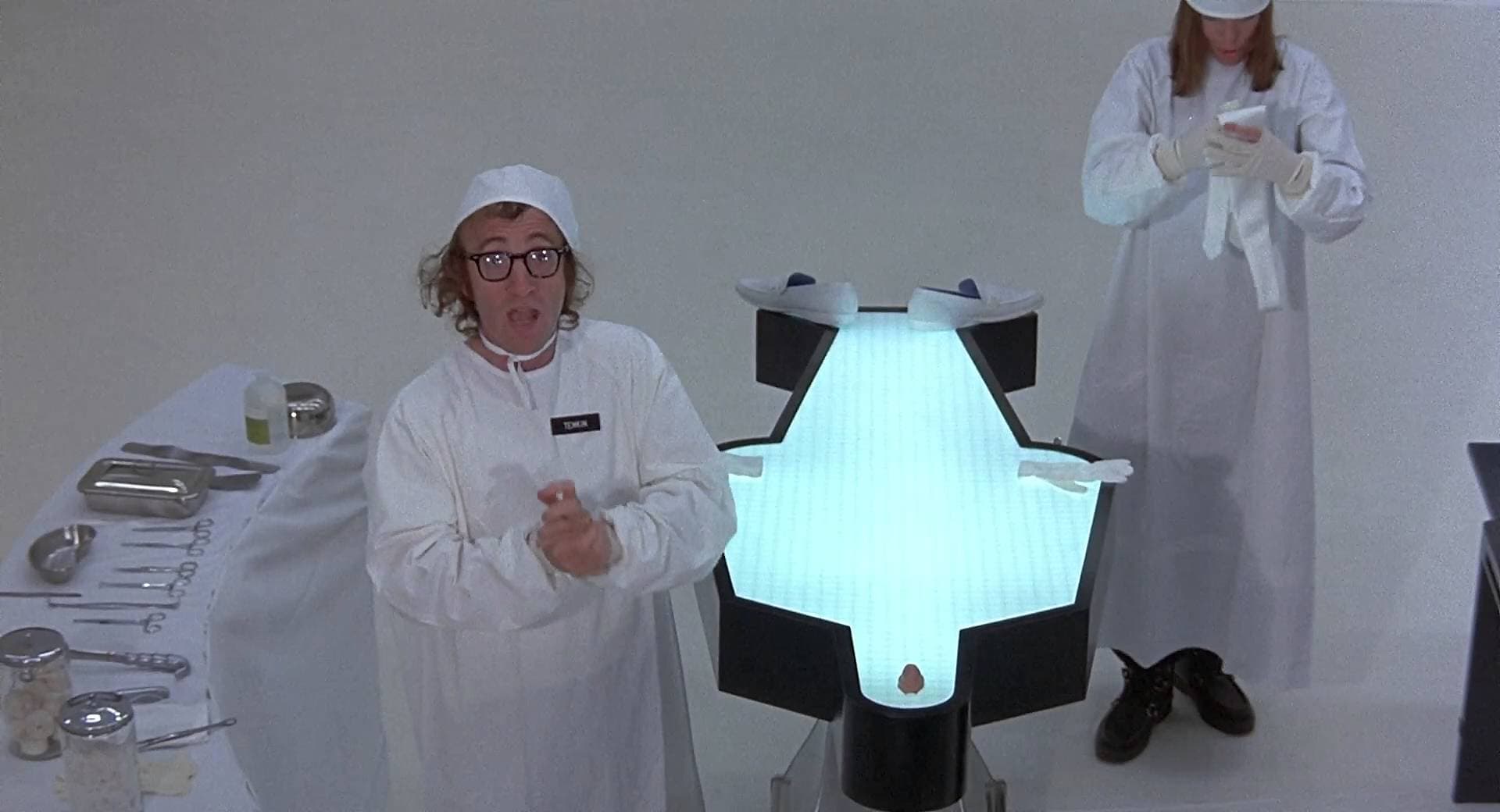

He manages to escape the police by disguising himself as a robot, one of the first, ingenious visual gags that pays homage to silent cinema and the physicality of Buster Keaton, a master of movement and deadpan expression, whom Allen has always openly declared as an inspiration. Miles' clumsy and neurotic body, contrasting with the mechanical elegance of the robot, becomes a vehicle for slapstick humor that blends with social satire.

He eventually meets an aloof and sophisticated poetess, Luna Schlosser, played by Diane Keaton at the peak of her magnetic beauty and her ability to combine vulnerability and intellect. Initially an emblem of futuristic conformity, Luna is an artist of the regime, but her superficiality is soon chipped away by Miles' irreverent anarchy. Their relationship, evolving from initial incompatibility to an affectionate, albeit bizarre, partnership, is the emotional heart of the film. It's a dynamic that foreshadows the unparalleled chemistry the two actors would develop in subsequent films, such as Annie Hall or Manhattan, but here framed within a context of pure surreal comedy. Keaton manages to give depth to a character who could have been a mere comedic foil, imbuing her with a grace that even resists the general madness.

Captured, Miles is subjected to brainwashing, an explicit reference to Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, but the horror of forced re-education is here transformed into Miles' hilarious inability to adhere to any dogma, an affirmation of his intrinsic neurosis as a form of involuntary resistance. The rebels save him and entrust him with the mission to kill the Leader, of whom only his nose currently remains (following an assassination attempt), which is about to be cloned. The idea of the nose as the last vestige of power, a fragment of the totalitarian face to be annihilated, is a stroke of genius, a visual metaphor for the emptiness of power and its reduction to absurdity.

Numerous grotesque inventions play with the science fiction genre, creating a kind of playful parody, elevating the film far beyond simple comedy. The satire is omnivorous, sparing nothing: from rampant consumerism to asphyxiating bureaucracy, from ephemeral fashions to future health obsessions, every aspect of society is wittily dissected. Food, for instance, is reduced to colored pills or tasteless cubes, in an era where humanity subsists only on wheat germ, soy steaks, and, exceptionally, four-hundred-year-old custard puddings. Nuclear energy has been banned in a world powered exclusively by natural and organic foods, a subtle irony about the pretense of a purified humanity that remains, at heart, profoundly dysfunctional.

One line above all, emblematic of Allen's stylistic signature: "Do I believe in God? You can call me an existential theological atheist. I believe in a Universe Intelligence with the exception of a few Swiss cantons.” This sentence is a distillation of Allen's thought, a philosophical oxymoron that condenses his constant questioning of the meaning of existence, faith, and non-sense, all seasoned with typical self-irony and the ability to defuse the seriousness of the theme with a prosaic and unexpected detail. It is Miles Monroe clinging to his irreducible neurosis as the only certainty in a mad world, an intellectual trapped in the body of a clown.

A special mention also for the "orgasmatic" machine that provides sexual pleasure to its users, a kind of telephone booth where one enters to have unilateral sex. This invention is one of the highlights of Sleeper's satire: sexuality has been reified, compartmentalized, made into a hygienic and solitary practice, almost a bureaucratic ritual. It's the triumph of the technologization of intimacy, a way to avoid the emotional disorder and relational complexity that human sex entails. But it is Miles himself, with his clumsiness and disarming normality, who reintroduces the spontaneity and chaos of analog sex, awakening not only Luna but the entire society from its emotional anesthesia. Sex not mediated by the machine becomes a revolutionary act, a return to primordial humanity.

A work of disruptive intelligence, where comedy flares from irony, from the protagonist's disenchanted and irreverent gaze, from his unsettling jokes. Sleeper is a bridge between the early Allen, known for pure comedic entertainment and rapid-fire gags, and the more reflective and auteur Woody Allen who would later explore the complexities of human relationships and intellectual neuroses. Here, his comedic aesthetic reaches full maturity, combining physical comedy inherited from silent film masters with refined and layered verbal humor, imbued with cultured references and brilliant one-liners. It is a film that, through paradox and farce, invites us to reflect on the nature of progress, individual freedom, and the persistent, ridiculous humanity that stirs beneath every claim of perfection. And it does so with an elegance and lightness that are the unmistakable hallmark of a comedic genius.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...