The Godfather Part II

1974

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

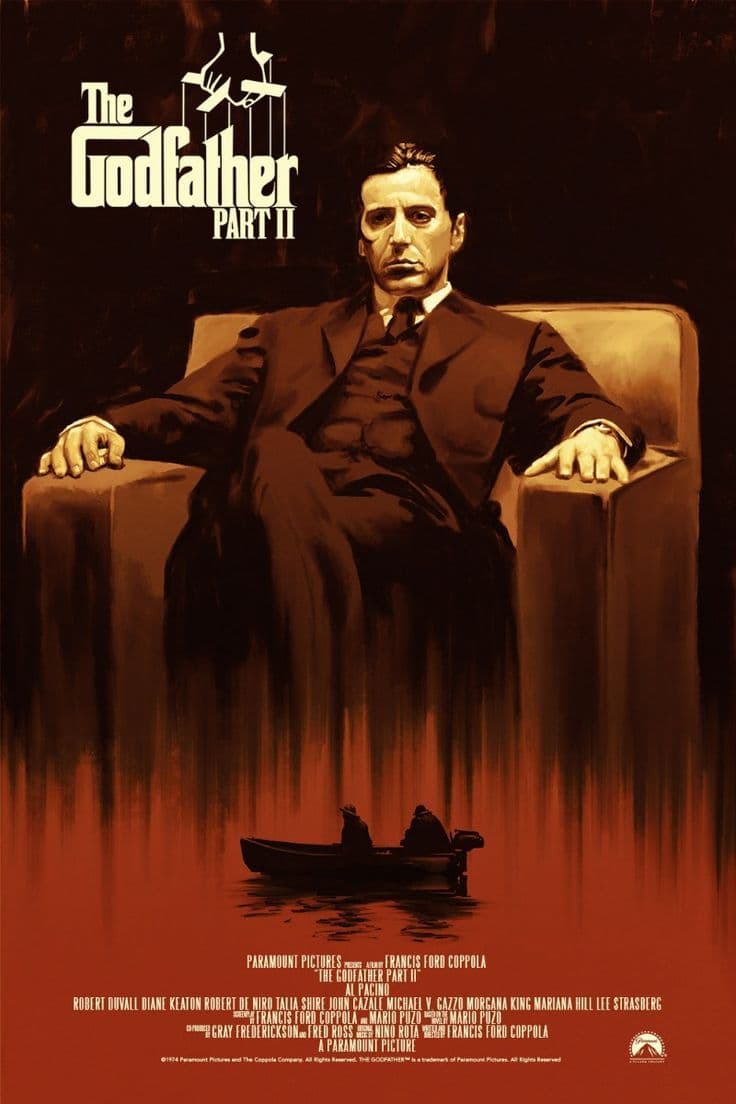

The film naturally and with iconographic power resumes the action and story of the first film, somehow closing a perfect circle. It is not a simple sequel, but a monumental symphonic extension, a second act that not only deepens the roots and ramifications of the family saga, but elevates its scope to a Greek tragedy of epic proportions. The "perfect circle" is not just narrative, but thematic: it is the inexorable cycle of rise and fall, of the contamination of power and the ineffable price of its preservation, a Moebius strip where beginning and end merge in the fatal transmission of a legacy.

The saga of the Corleone family, taken from Mario Puzo's novel, continues, but it does so with a stratification and psychological depth that transcend the, albeit valuable, literary source. The film stands as a solemn diptych, a two-faced fresco that reflects the American soul through the prism of its darkest shadow.

Michael has taken his father Vito's place and is managing the family's affairs, but with a cold, detached ruthlessness that foreshadows his definitive dehumanization. In parallel, through flashbacks, we learn about the childhood and youth of Vito Corleone, played in his younger period by Robert De Niro. The choice of this structure is never didactic; it is, on the contrary, a narrative virtuosity that allows Coppola to juxtapose, with merciless irony, the pragmatic and bloody idealism of Vito, the founder, with the sterile and paranoid brutality of Michael, the successor.

The film proceeds divided into two parts: on one side, the story of the Patriarch and how he reached the summit, an Odyssey of misery and redemption in early 20th-century America, where violence emerges as a defense of an abandoned community and transforms into an instrument of parallel justice; and on the other, Michael's ascent to leadership of the family in New York, a path that unfolds in disillusionment and betrayal, methodically destroying every emotional and family bond in the name of an abstract preservation of power. If Vito builds an empire to protect his loved ones, Michael dismantles it, piece by piece, in the illusion of securing it. The sequence of the kiss of betrayal to Fredo, bathed in twilight and charged with Shakespearean tragedy, remains one of cinema's emotional and moral peaks.

De Niro's performance in characterizing young Vito is remarkable: an acting tour de force that goes far beyond simple imitation of Brando. De Niro does not merely mimic his gestures or hoarse voice, but embodies their genesis, the primordial spark of that sly composure that conceals an unwavering determination. Vito is a calm and loving man, even gentle in his affections, but ready to explode in cold and ruthless violence to defend his business, his family, his nascent community. His is an almost paternalistic violence, targeted, surgical, never gratuitous, which makes him an "man of honor" in the distorted but codified sense of the term.

In this sense, the killing of Fanucci (played by an excellent Gastone Moschin) is paradigmatic: after being appeased with an offer to delay a protection payment, he is killed on his doorstep by Vito, who is lying in wait in the shadows, with a rag wrapped around his pistol. This scene is not just a murder, but a rite of initiation, a dark consecration that sanctions the birth of a new power. Vito does not kill out of blind revenge, but for affirmation, to demonstrate his supremacy and his ability to protect "his own." The detail of the rag around the pistol is a stroke of genius, highlighting the cold pragmatism of the act, its silent and fatal essence.

The interplay of light and shadow is wonderful, with a light bulb that switches on and off, intermittently revealing a Mephistophelian De Niro lurking in the shadows, ready to strike. It is a moment of pure cinema, a visual exploration of the duality of the human soul and the genesis of evil, evoking the darkest atmospheres of film noir and the expressionistic suggestions of German cinema. Gordon Willis's cinematography, by the "Dark Prince of Cinematography," reaches unparalleled heights here, shaping darkness not as an absence of light, but as a menacing presence, dense with meaning and foreboding. His palette of browns and sepia imbues the film with a timeless aura, almost like a faded dream, yet at the same time a solid, ineluctable historical reality.

A fundamental work that cannot be overlooked, thanks above all to Coppola's masterful direction, which never allows a moment's pause as the plot unfolds. His is an orchestral direction, masterfully balancing two complex timelines, intertwining them with surgical precision and a sense of drama rooted in the great Italian operatic tradition. The screenplay, written by Coppola himself with Mario Puzo, is a masterpiece of structure and dialogue, chiseled with the same care with which a craftsman forges the strongest steel.

Every shot, every set design, every play of light denotes immense craftsmanship, a meticulous attention to detail that helps build a credible and all-encompassing universe. From the vibrant scenes of Little Italy to the desolate villas on Lake Tahoe, from the opulence of 1950s Las Vegas to the sobriety of rural Sicily, the setting is never mere background, but a character itself, a mirror of the Corleones' soul. The music of Nino Rota and Carmine Coppola, melancholic and pervasive, weaves a sound fabric that amplifies the sense of fatality and nostalgia, elevating every scene to an announced requiem for the family and for the corrupted "American dream."

An evocative and hieratic film in its narrative power, a cornerstone of world cinema that continues to resonate, with its dark magnificence, like an echo of the eternal questions about power, family, loyalty, and the solitude that accompanies anyone who dares to defy destiny.

Comments

Loading comments...