Il Sorpasso

1962

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Opening scene: In the silent, deserted Rome of an August afternoon, a car wanders desperately in search of a faint sign of life. It is not the post-apocalyptic desolation Antonioni would have painted, but rather an almost surreal quietness, the calm before the storm of an Italy that, despite being immersed in the din of the economic boom, still found corners of an ancient, almost rural, solitude. It is a Rome emptied not by catastrophe, but by the holiday exodus, an alienating pause in which the echo of the future, frenetic and inexorable, is already palpable.

Our point of view is that of the camera, in the passenger seat behind the driver, with Riz Ortolani's saxophone in the background telling us there is still a faint hope. It is a melancholic hope, steeped in the bittersweetness typical of commedia all'italiana, a sonic premonition of a journey that cannot conclude with a conventional happy ending. Ortolani’s music is not mere accompaniment, but a parallel narration, capable of suggesting the unease and ephemeral joy that will punctuate the subsequent hours, almost an anticipated requiem for an era and a way of being.

The man tries in vain to use a phone behind a rolling shutter, then disconsolately drives off, roaring into complete solitude. This gesture, so simple and everyday, acquires an almost universal meaning: disconnection, the impossibility of establishing authentic contact, the isolation that lurks even in the heart of modernity.

This is how one of the most beautiful films of the Italian post-war era begins. Dino Risi’s "Il Sorpasso" is not just a film, but a living fresco, a visual and narrative compendium of an Italy in rapid and convulsive transformation. It is the swan song for a certain innocence, and the bitter dawn of a new era.

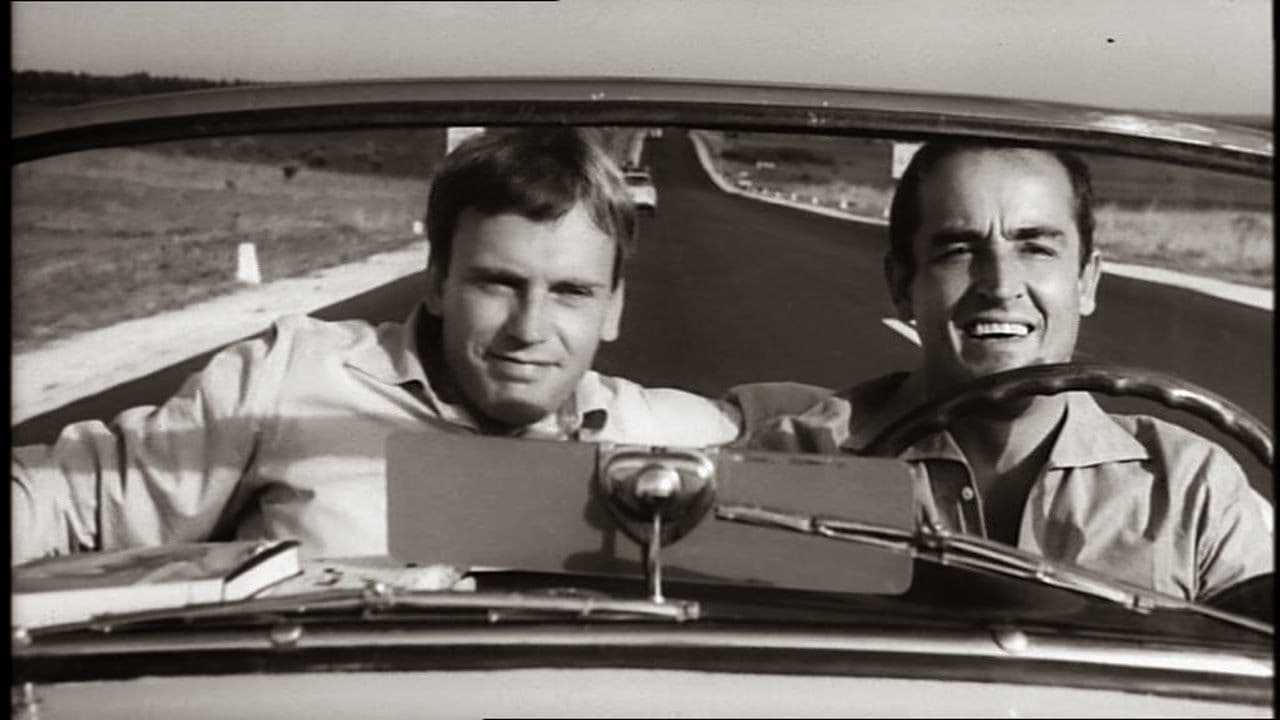

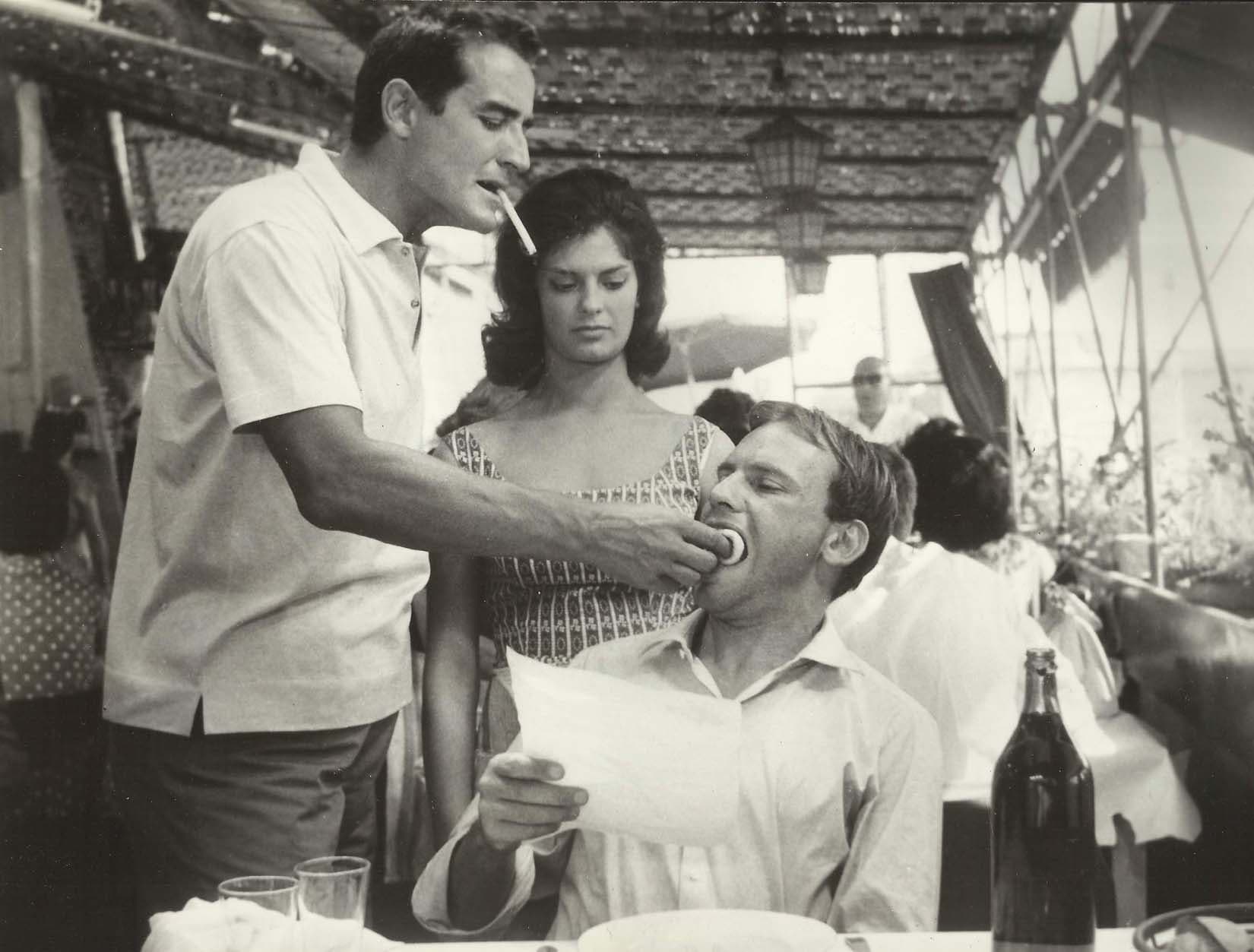

This braggart (in French, the film was released with the significant title “Le Fanfaron,” almost echoing Plautus’s Miles Gloriosus) reluctantly involves a law student in a ramshackle journey where, at each stop, he tries to persuade the student to stay with him a little longer. Bruno Cortona, portrayed with an almost primordial verve by a Vittorio Gassman in a state of grace, is the archetype of the average Italian of the boom era: cynical, vital, superficial, yet also capable of a desperate, almost childlike, search for companionship and meaning. His is an insatiable hunger for life, for experiences, for pleasure, which translates into an existential nomadism characterized by excessive gestures and bombastic words. Beside him, the sober and fragile figure of Roberto Mariani, portrayed with delicate introspection by Jean-Louis Trintignant, serves as a mirror and a counterbalance. Roberto is not merely a student, but the symbol of a more reflective, timid Italy, perhaps still bound to intellectual and moral values that the fervor of consumerism is rapidly eroding. Their encounter, casual and dictated by Bruno’s irrepressible impulse, proves to be the narrative device for a picaresque odyssey which is, in reality, a descent into the contradictory soul of the Sixties.

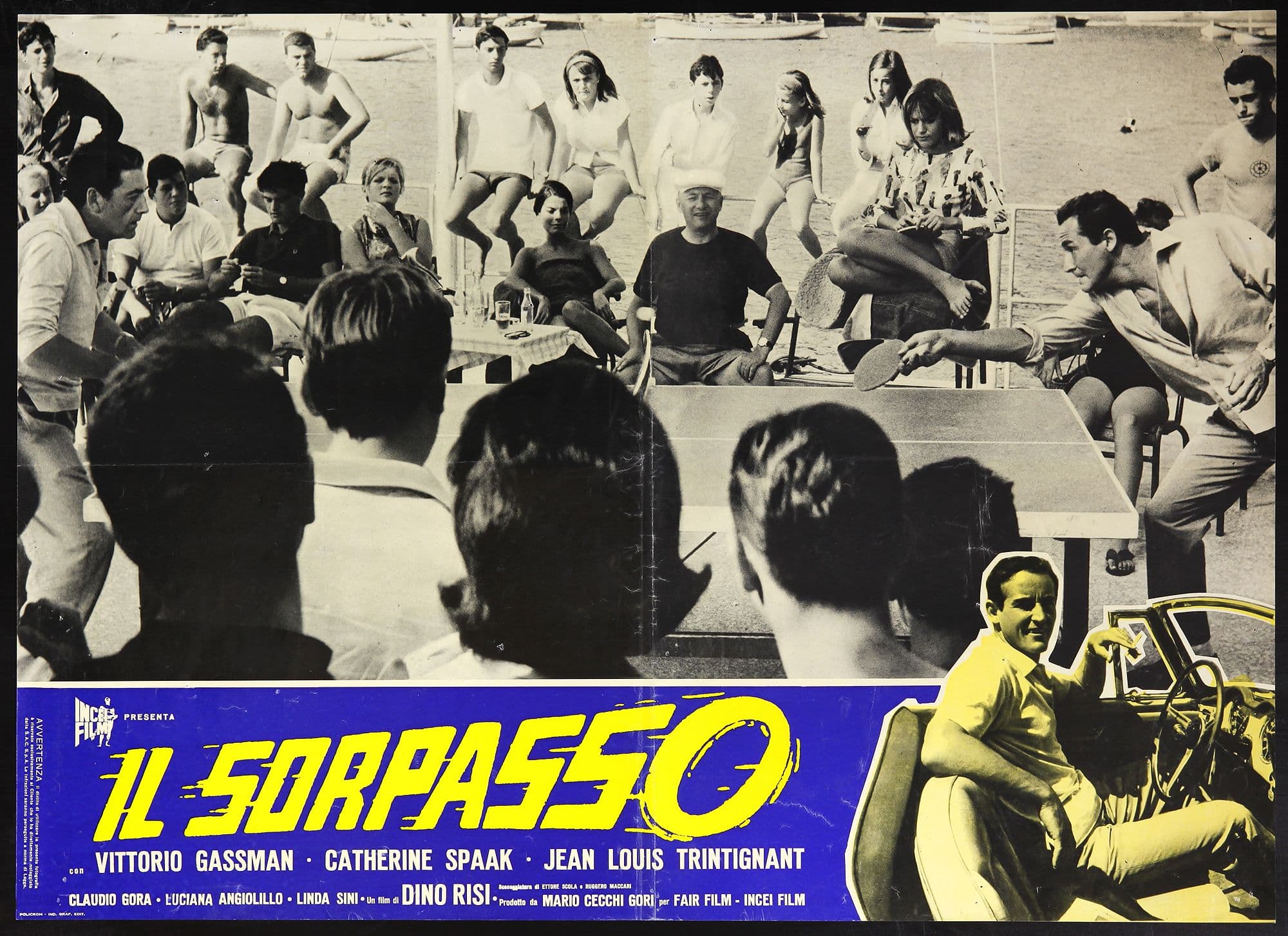

It will be the occasion for a journey through trattorias, road accidents, beautiful foreign tourists, obliging waitresses, furious ex-wives, and pleasure-seeking parties. Each stop is a snapshot of customs, a micro-anthropological essay on the society that was taking shape: the explosion of tourism, the liberalization of customs (though still superficial), the ephemeral well-being that translated into an almost ritualistic ostentation. The journey has no precise destination; the escape itself is its purpose, a constant acceleration towards an undefined future. The Lancia Aurelia B24 Spider, a true co-protagonist, is not merely a means of transport but a tangible symbol of that desire for speed, escapism, and modernity that characterized the decade. Through the windshield, Risi offers us a visual palimpsest of the "Italian miracle": highways under construction, crowded beaches, expanding cities, but beneath the glossy surface, a certain emptiness emerges, a spasmodic search for a pleasure that never fully satisfies.

The contrast between Bruno’s bravado and Roberto’s sober introspection is the key to understanding the film: two opposite poles briefly drawn together by the flow of events, ultimately it is the contrast between clamor and silence, worldliness and intimacy, appearing and being. Bruno embodies exhibited exteriority, life lived on the surface, an existence built on the simulacrum of optimism and invulnerability. Roberto, conversely, represents depth, the search for a more authentic meaning, the unease in the face of a world that seems to have lost its moral compass. Their dynamic is a dance between the two, a seesaw between Bruno’s contagious exuberance and Roberto’s latent melancholy, who slowly allows himself to be seduced by an energy that is alien to him, yet irresistible. Bruno’s booming laughter and his perennial optimism hide a profound solitude, an inability to establish lasting bonds, a life composed of escapes and casual encounters, but never truly significant. It is the tragedy of a man who, despite living life to the fullest, never truly lives.

This kind of harmonization of contrasts makes this film a work suspended between the extremes of reality, a fascinating glimpse into the contradictions of 1960s society. “Il Sorpasso” is a masterpiece of commedia all'italiana, a genre of which Risi was one of the foremost exponents, capable of blending its social satire with human tragedy. Its laughter is often a sneer, its lightness conceals an existential weight. The ending, so abrupt and unexpected, is not a mere plot twist, but the inevitable conclusion of a frantic race, the exclamation point on the transience of an era and the fragility of a certain way of life. It is a bitter metaphor for the end of an illusion, the violent awakening from a dream of eternal youth and boundless freedom. The impact of that final moment transcends the plot to imprint itself on collective memory as the epiphany of an Italy that, in its “passing over” everything and everyone, ended up passing over itself. And precisely in this disarming lucidity, "Il Sorpasso" continues to speak to us, with the prophetic force of a classic that, through the lenses of the past, continues to reflect the uncertainties and frenzies of our present.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...