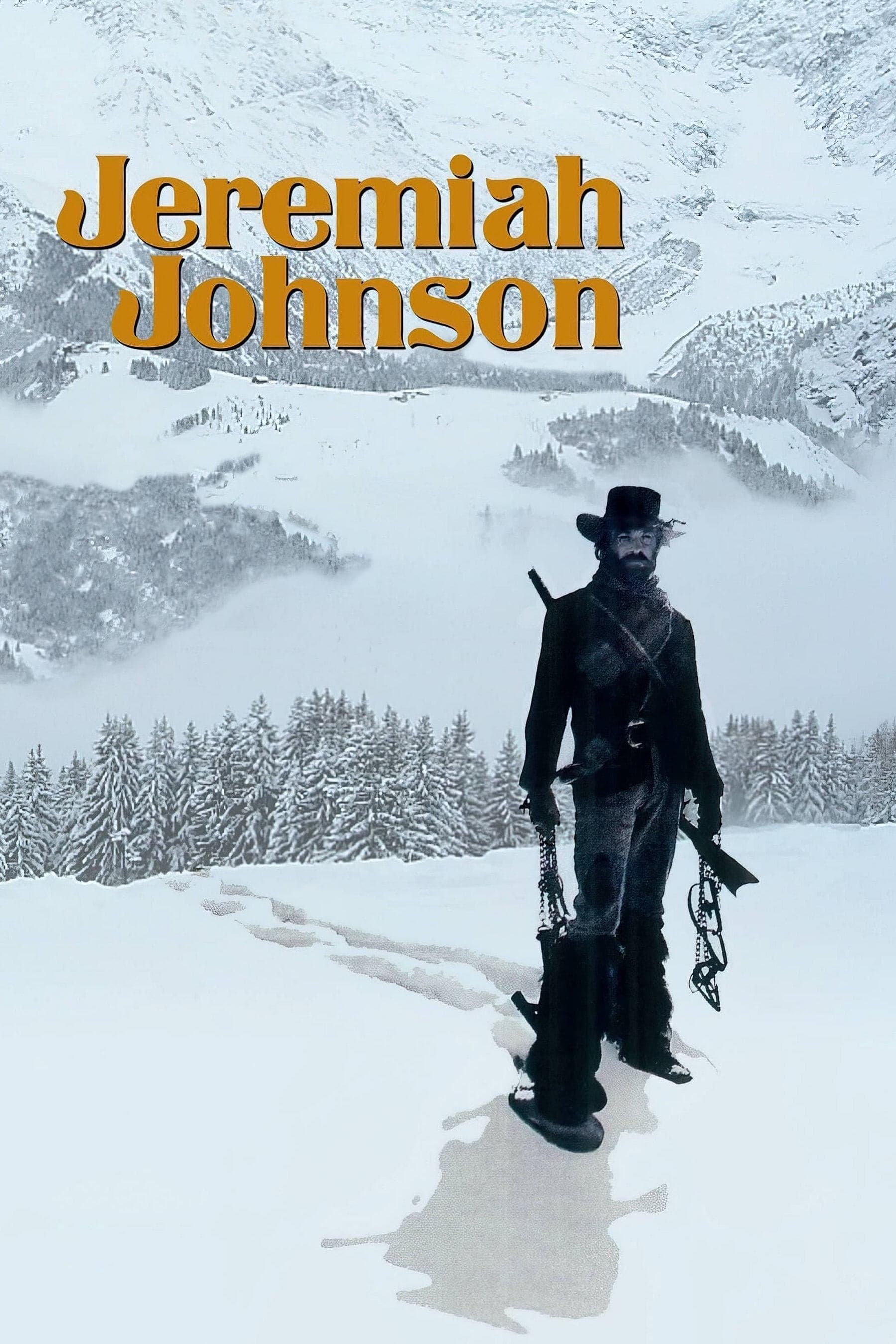

Jeremiah Johnson

1972

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

A splendid, intense, evocative, and universal work in which Robert Redford plays an ascetic trapper who, rather than embracing the encroaching progress that engulfs landscapes and men, prefers solitude and isolation. More than a mere survival story, Red Crow, You Won't Get My Scalp establishes itself as a profound meditation on the primordial relationship between man and wild nature, an almost mythopoeic epic that transcends the boundaries of the Western genre to question the very essence of existence and individual freedom. It is a film that, though rooted in the specific setting of the 19th-century American frontier, resonates with eternal questions, speaking of disillusionment with civilization, the search for authenticity, and the price to pay for an uncompromised life.

Jeremiah, in fact, has no love at all for the commotion of the burgeoning new metropolises and decides to isolate himself from the world by retreating into the mountains. His escape is not a mere strategic retreat, but a radical philosophical choice, a rejection of the empty promises of industrial civilization and its relentless advancement, which was beginning to corrode not only the landscapes but also the very soul of America. He is the archetype of the American individualist, not the conquering and imperialist one of Manifest Destiny, but the hermit, who seeks a lost paradise, a tabula rasa on which to rewrite his existence far from social hypocrisies and constraints. In this sense, Jeremiah is not just a trapper, but a pragmatic philosopher who seeks truth in the deafening silence of the peaks.

He lives by hunting and fishing and encounters the most varied humanity: a somewhat eccentric hunter and an old Native American chief whose daughter he will marry. These encounters are the pulsating heart of the film, shaping Jeremiah no less than solitude itself. The eccentric and wise "Bear Claw" (played by Will Geer) becomes a mentor figure for him, a master of survival and mountain wisdom, a bridge between the newcomer's crude naivete and the harsh reality of the wilderness. The figures of Paints His Shirt Red, the Flathead chief, and his daughter Swan, offered to Jeremiah as a wife, represent instead a contact with a cultural otherness that forces him to confront distant rituals, traditions, and values, yet intrinsically tied to the land. Swan, with her innocence and eloquent silence, is the symbol of the unspoiled purity that Jeremiah seeks, and her presence brings a fragile, yet intense, semblance of family and peace into his solitary world. It is an idyllic period, a kind of rediscovered Eden, which, however, like all Edens, is destined to be violated.

Against his will, he gets a job as a scout for a military detachment. While escorting the soldiers, he finds himself having to violate a Crow Native American burial ground. This sequence is a crucial turning point, imbued with bitter irony. The man who had sought peace in nature finds himself, against his will, collaborating with the forces of "civilization" he had renounced, ultimately committing an act of sacrilege in a place sacred to the Native Americans. The violation of the burial ground is not just a physical act, but a metaphor for the desecration of an entire way of life, a disregard for the sanctity of the land and the memory of ancestors. It is the classic collision between two worlds, two irreconcilable visions of existence, where the logic of progress and conquest annihilates spirituality and respect for the past.

In retaliation, the Crow kill his wife. Thus begins Jeremiah's vengeance in a sort of cathartic journey: an epic that will take him to the very edges of myth. Jeremiah's revenge is not a mere thirst for blood, but an inevitable consequence of the violation suffered, a response to the destruction of his fragile equilibrium. From a solitary and pacifist trapper, he is transformed into "Red Crow," a legendary and feared figure who embodies the justice of the wilderness. This journey is not only cathartic but transformative: Jeremiah no longer seeks peace, but revenge, becoming himself an integral part of the wild landscape, an extension of its implacable natural law. It is an escalation of cyclical violence, a silent dialogue between man and nature, between the desire for oblivion and the need to face consequences. The film depicts this transformation with an almost stoic sobriety, allowing actions and reactions to unfold with the force of an ineluctable destiny, projecting the protagonist into an almost archetypal dimension, that of the solitary warrior defending his integrity in a hostile world. It is a tragic parable, an elegy for lost innocence.

Sydney Pollack, directing and leveraging the great work of cinematographer Duke Callaghan (ten years later he would be called to work on Conan the Barbarian by John Milius), films with great cleanliness, clarity, and sobriety, restoring to the viewer what the protagonist desperately sought: the peace of the most unspoiled nature, the biting cold that whips the face amidst the snows of Montana, the murmur of a stream in the forests of Wyoming. Pollack's mastery lies precisely in this ability to balance the epic grandeur of the landscape with the intimacy of human drama. Unlike traditional Westerns that often extol conquest and virile heroism, Pollack adopts an almost anti-Western approach, favoring contemplative observation, daily survival, and a deep spiritual connection with the environment. The direction is essential, almost spartan, allowing the landscape to become a true character, imposing and indifferent, but also a source of life and inspiration.

Duke Callaghan's cinematography is simply breathtaking, capturing the magnificence and brutality of the Rocky Mountains with an almost documentary realism, yet imbued with lyricism. The wide shots that immortalize the vast snowy expanses and dense forests are not mere backdrops, but expressions of Jeremiah's state of mind, amplifying his sense of solitude and his dependence on the elements. The natural light, the skillful use of backlighting, and the ability to render the texture of cold and snow, imbue the film with a visceral sense of authenticity. It is Callaghan who manages to make tangible the murmur of the stream, the wind through the trees, the silence broken only by the sounds of wildlife. His work is fundamental in conveying the idea that nature is not only beautiful, but a powerful and untamed entity that can give and take away, shaping the man who ventures into it. In this context, Robert Redford is not just an actor, but an almost sculptural figure, perfectly integrated into the landscape; his lean physique and melancholic presence merge with the desolation and grandeur of the scenery.

For comic book enthusiasts: the character of Jeremiah Johnson, with Redford's face, would lend his likeness to Ken Parker by Berardi and Milazzo, an Italian cult comic from the 1970s. The resonance of Red Crow, You Won't Get My Scalp in the collective imagination, and particularly in comics, testifies to its universality. Ken Parker, the wandering "long rifle," shares with Jeremiah not only Redford's face, but above all his soul: the choice to live on the fringes of civilization, a deep sense of justice, a repulsion for gratuitous violence, and an attachment to the values of nature. Both characters represent a counter-narrative to the traditional hero, preferring reflection over impulsive action, compassion over cruelty, empathy towards the oppressed over the celebration of power. It is a film that, fifty years after its release, continues to speak to the heart of anyone seeking a sense of freedom and a return to the essential, in an increasingly frenetic and dehumanizing world. A timeless gem, a hymn to human resilience and the inexorable power of nature.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...