Judgment at Nuremberg

1961

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

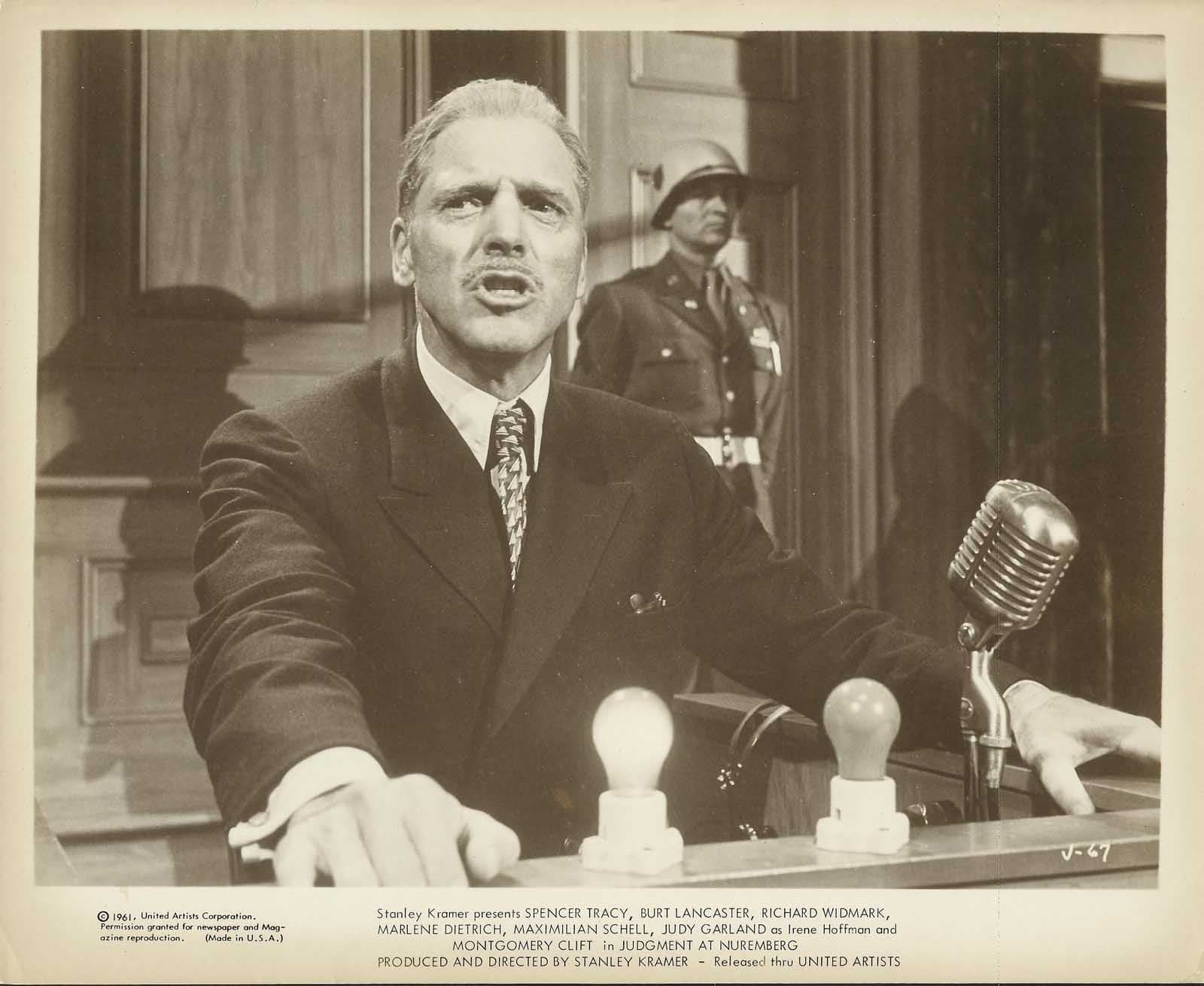

A genuine parade of stars for a production that was nothing short of colossal. It was not merely an all-star cast – Spencer Tracy, Burt Lancaster, Richard Widmark, Maximilian Schell, Marlene Dietrich, Judy Garland, Montgomery Clift, a true pantheon of cinematic giants – but a masterful assembly of talents that lent a specific gravity and an almost operatic resonance to the narrative. Stanley Kramer, with his committed filmmaker's spirit and his recognized ability to direct "problem pictures," outdid himself in this endeavor, orchestrating a courtroom drama that transcended mere genre to become an ethical and historical reflection of universal scope. The production scale, the set design accuracy, and the meticulousness in reconstructing events were not mere embellishments, but functional elements that lent the story an imposing gravitas, a sense of almost documentarian solemnity that anchored the fiction to the raw reality of the facts.

In harmony with the democratic vision and renewed idealism that characterized John F. Kennedy's America, then in its first year of presidency, a work emerged that, for the first time and with surprising intellectual courage, did not relegate Nazis to the role of purely evil and one-dimensional entities, but attempted to present them in their complex and terrifying humanity. This was a revolutionary approach for Western cinema of the era, which dared to explore the grey nuances of a regime painted (not wrongly) as absolute evil. Kramer and screenwriter Abby Mann (awarded an Oscar for his masterful adaptation) delved into their complex emotional and psychological spheres, revealing them as sentient beings, sometimes even refined intellectuals or honest servants of the state, who found themselves, or chose, to act at the mercy of events or, worse, became complicit in unspeakable abominations in the name of a perverse ideology. This examination was not an attempt at absolution, but a challenge to the viewer to confront the uncomfortable truth that evil can sprout even in the most common of men, or in the most brilliant of intellectuals, a prefiguration, in a sense, of the theses on the "banality of evil" that Hannah Arendt would articulate shortly thereafter.

The Nuremberg trials thus become the ideal stage where Kramer, with almost Shakespearean mastery, juggles the contrasting sentiments of victors and vanquished. The courtroom, in its austere bareness, transforms into a theater of conscience, a kind of silent conflict of consciences and ideals that precedes and underlies the fierce dialectic of legal proceedings. Every testimony, every cross-examination, every silence laden with meaning, contributes to weaving a tapestry not only of legal facts, but of profound moral and existential questions. The innovative use of newsreel footage and original Holocaust films, projected in the courtroom, is not a mere documentary expedient, but a gut punch, an unavoidable reminder of the rawest and most inhuman reality that that court was called upon to judge, contrasting cold legality with the unspeakable brutality of history.

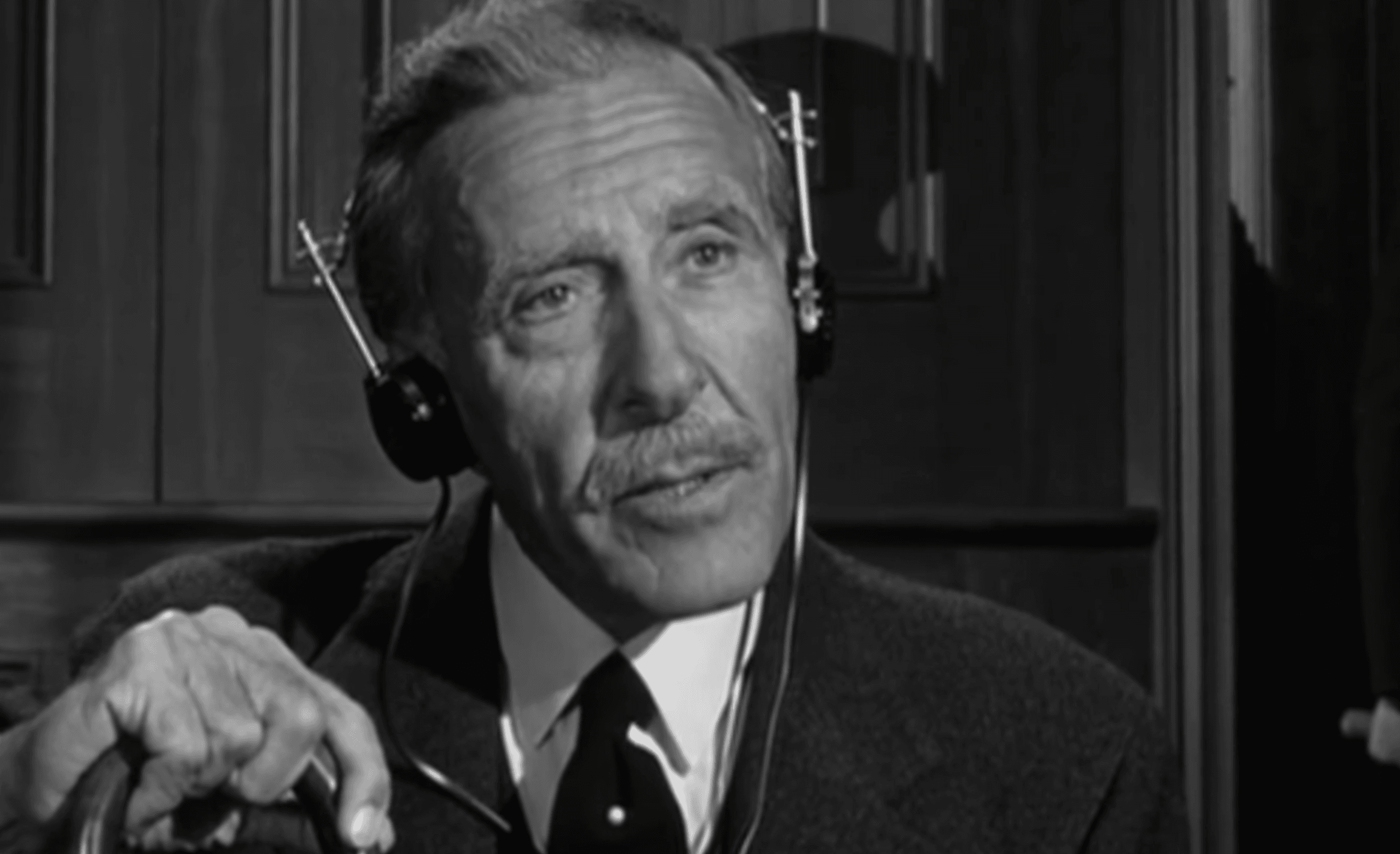

The central figure of the story is American judge Dan Haywood, portrayed with unforgettable dignity and quiet authority by Spencer Tracy, called upon to preside over and coordinate the proceedings. His task is not only to guide a legal proceeding, but to ensure that justice and historical condemnation can find a perfect balance, a juncture between the rigor of the law and the moral imperative to recognize and sanction unprecedented crimes against humanity. Haywood embodies the search for a universal truth and a principle of individual responsibility that transcends political contingencies. His integrity is severely tested not only by intricate legal arguments, but also by pressing diplomatic interferences and veiled threats from an American establishment more concerned with the balances of the nascent Cold War and the need for a rearmed and allied Germany than with the full and unconditional application of retributive justice. His solitary decision-making, the weight of history on his shoulders, make him an archetype of the modern judge, guardian of an ethical and legal order in the making.

In filigree, the complex personalities of each of the Nazi leaders in the dock emerge, each with their own baggage of memories, errors, compromises, and above all, their own defense strategies. From Ernst Janning (Maximilian Schell, in an Oscar-winning performance), the refined and idealistic jurist who embodies the moral collapse of the German intellectual elite and its abdication of reason, to the cynical and disdainful Rudolf Hofstetter (portrayed by Max von Sydow), who represents the remorseless perpetrator, the film explores the different facets of guilt. It is not just the direct guilt of the executioners, but also the, perhaps more insidious, guilt of silent complicity, of moral indifference, of the "banality of evil" that allows totalitarian systems to prosper. The film keenly interrogates the dichotomy between individual responsibility and obedience to authority, pushing to consider how thin the line was that separated the common man from the accomplice of unimaginable crimes, and how easy it was for the intellect to deviate from the straight path to serve the blind logic of raison d'état.

It is an extraordinary work that allows the humanity of people to shine through the spoken word, sometimes in their sublime capacity for resilience and testimony, sometimes in their abject fall. In parallel, it denounces the intrinsic inhumanity of history when it allows itself to be shaped by destructive ideologies and the blindness of prejudice. But it is above all in probing the diabolical side of raison d'état that the film reaches its thematic apotheosis. Not only the Nazi raison d'état that justified the annihilation of entire peoples, but also the more subtle and insidious one of the victorious powers that, just a few years after the end of the war, found themselves having to balance the principles of justice with the new, urgent geopolitical needs of a world already shaping up to be divided. The shadow of the Cold War stretched over the tribunal, insinuating the doubt that justice could be sacrificed on the altar of realpolitik.

Also a great lesson in international law and, tout court, in democracy, laying the groundwork for a reflection on crimes against humanity and the necessity of supranational jurisprudence. The film's strength lies in its ability to translate abstract concepts such as justice, guilt, responsibility, and forgiveness into a palpable human drama, making them accessible and urgent. To be viewed with dual significance: didactic, for its acute historical and legal analysis and its perpetual relevance as a warning against intolerance and the denial of human dignity; and aesthetic, for its superb direction, memorable performances, and a screenplay that is a monument of intelligence and sensitivity. "Victors and Vanquished" is not just a cinematic masterpiece, but an ethical beacon that continues to illuminate the darker zones of the human psyche and collective history, questioning our capacity to judge and, above all, to remember.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...