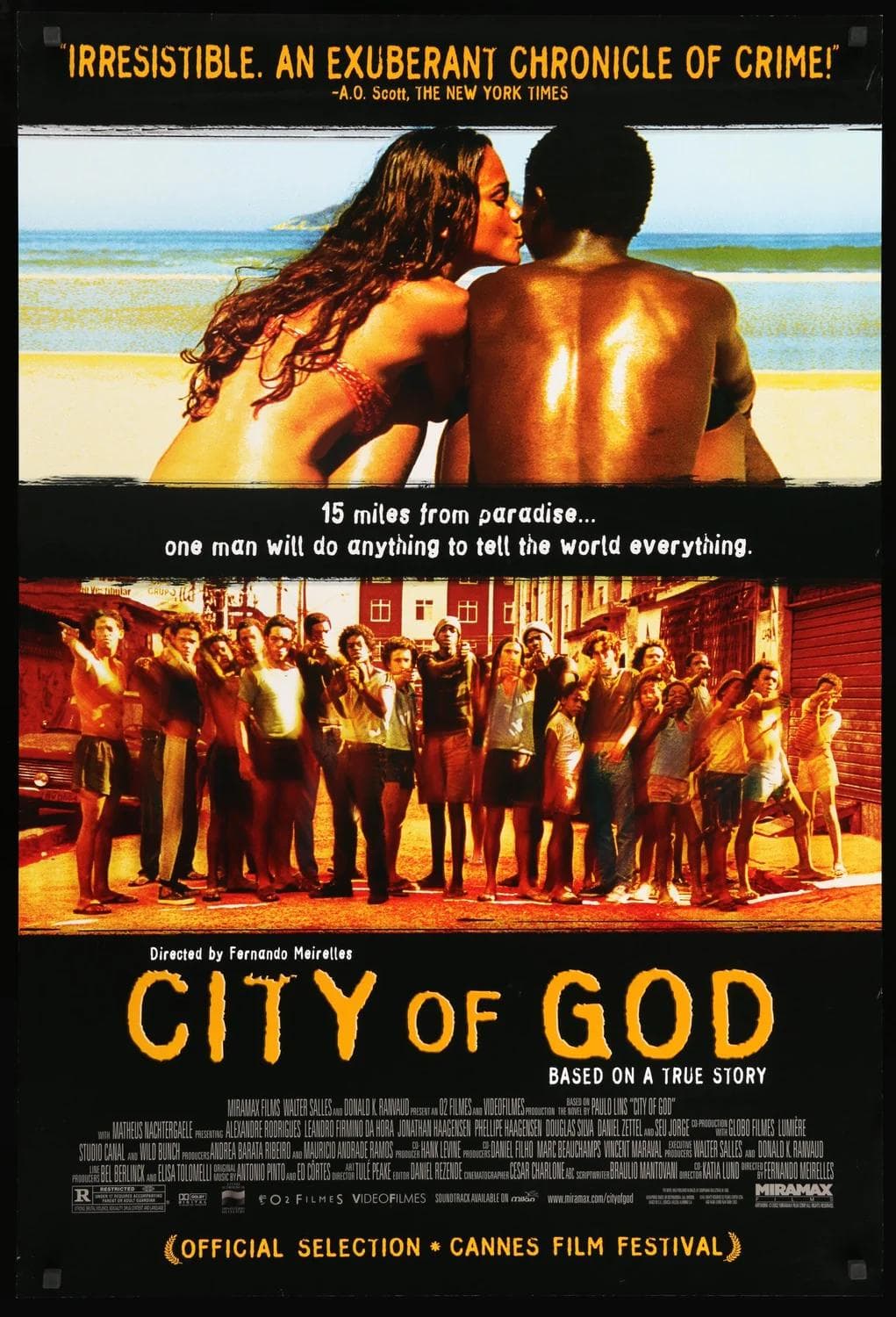

City of God

2002

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Directors

A violent and direct work, it surprises with its raw realism but also with the performances of the young actors, all rigorously non-professional. This "raw realism" is not merely a stylistic choice; it is a declaration of intent, a moral imperative that roots itself as much in Italian Neorealism as in Brazilian Cinema Novo, movements that sought to restore the naked and raw truth of social realities, often with aims of political denunciation. The choice of non-professional actors, recruited from the very communities that form the plot, is not just a casting expedient, but a radical act that dissolves the boundaries between fiction and lived experience, imbuing every gesture, every gaze, with an almost documentary veracity, irreproducible by professional actors, no matter how talented.

It is a coming-of-age novel that narrates the story of two boys growing up in the cruel and cursed environment of City of God, a labyrinthine favela on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. Far from being a mere backdrop, Cidade de Deus emerges as a character in itself, a monstrous urban entity made of corrugated iron, bricks, and a desperate, tenacious human resilience. Its labyrinthine alleys are suffocating arteries, clogged with broken dreams and trampled hopes, a closed ecosystem where the laws of the outside world are nullified, replaced by a brutal and self-imposed order. This "non-place" becomes a crucible that forgives divergent destinies not so much by free choice as by the overwhelming weight of circumstances.

Buscapé wants to leave that non-place; his aspiration is to become a professional photographer. His camera is not only a tool, but a shield and a passport. It offers him a privileged vantage point, a role as a detached witness in a universe where detachment is an almost unthinkable luxury. Through his lens, the chaos of the favela is framed, rendered intelligible, even intrinsically fascinating in its raw reality. Photography becomes his voice, his agency, a subtle act of rebellion against the narrative of violence that threatens to engulf him. He seeks to capture reality, not to be its victim, transforming observation into a form of salvation and personal redemption.

Dadinho is a boy consumed by that spiral of violence and who has become complementary to the logic of subjugation that reigns in the alleys of City of God. His transformation into Zé Pequeno, young drug boss, undisputed leader of local crime, is a chilling descent into the heart of darkness, a desolate warning of how childhood innocence can be irrevocably corrupted by an environment devoid of any glimmer of hope. His evolution is less a choice than an inevitability, a logical – albeit terrifying – outcome of a system that rewards brutality and punishes vulnerability. Zé Pequeno embodies the ultimate expression of the favela's distorted social contract: force is law and power is exercised through terror. His reign is a miniature totalitarian state, a microcosm of absolute power that thrives in the vacuum left by state abdication. His violent methods will very soon cause a gang war with tragic implications. His pathological violence is not random; it is a meticulously constructed performance to cement his authority and eliminate dissent, a perverse form of social engineering.

The director's hand is extremely astute in unearthing before our eyes the aura and raw vitality of a youth overwhelmed by the environment, by the squalor of trampled and overwhelmed ideals, by a misery that catalyzes a Darwinian urge to emerge. Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund orchestrate this epic of survival with breathtaking dynamism that mirrors the frantic energy of the favela itself. Daniel Rezende's tight and virtuosic editing, often cited as revolutionary, does not merely advance the plot; it plunges us into a sensory overload, into constant threat, into fleeting moments of joy and despair. César Charlone's vibrant and often sun-drenched cinematography, paradoxically, renders misery almost sublime, highlighting the stark contrast between Brazil's natural beauty and the man-made ugliness of its social disparities. This stylistic exuberance, however, never detracts from the film's central message: a profound indictment of a society that allows such conditions to proliferate, where human lives are expendable commodities in a market of desperation.

A dimension where every moral judgment is frozen and where every action of the protagonists is governed or bent by a bleak dehumanization that submerges every other ethical implication. The film shuns any easy moralism, instead forcing the viewer to confront the brutal logic underpinning the characters' actions. It is a vision in which ethics are not merely suspended, but actively inverted, where survival itself becomes the ultimate, and often the only, virtue. This ethical desert, sculpted by generations of systemic neglect, poses a terrifying question: what happens when the very foundations of human dignity are eroded into dust?

One of the most emotionally impactful scenes is certainly the killing of a favela child guilty of having stolen bread from Zé Pequeno's table. He, with an amused sense of justice, has him killed by the youngest boy in his gang to teach the others how to behave in his presence. This scene, in particular, is a punch to the gut, a moment of profound moral abjection, a rite of initiation not only for the youngest killer but also for the viewer into the absolute lack of redemption in the favela. The whole is filmed with a terrifying and disenchanted realism that recalls Pasolini's Accattone, not only for its raw depiction of the violent subproletariat, but also for its allegorical weight. Like Pasolini in his chronicles of the Roman lumpenproletariat, "City of God" delves into a world abandoned by official society, where new, brutal codes emerge. But while Pasolini often imbued his realism with a tragic, almost sacred aura, Meirelles presents a reality stripped of all romanticism, a universe where the sacred has been replaced by the profane, where innocence is a weakness and cruelty a necessary survival skill. The impassive gaze of the camera, much like that of a documentary, captures the horror without editorializing, inviting us to be witnesses rather than to judge from afar. This uncompromising honesty finds echoes in a varied cinematic genealogy, from Ken Loach's social realism to early Scorsese's gritty urban chronicles, yet "City of God" carves out its own unique space, imbuing this hyperrealism with a kinetic, almost hallucinatory energy. It is a vision that manages to be both epic in its scope and intimately terrifying in its attention to the individual cost of social collapse.

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...