La Dolce Vita

1960

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

An iconic Fellini paints a fresco of upper-bourgeois life in 1960s Rome. An era, that of the “Economic Miracle,” in which the capital was no longer merely the center of politics and religion, but the epicenter of unbridled worldliness, of an international glamour that attracted Hollywood stars, magnates, and a new aristocracy of money. It is a grandiose and unsparing portrait, where the veneer of luxury and entertainment conceals a moral void, a profound anomie that corrodes the soul of the city and its most prominent inhabitants.

It narrates the story of a gossip journalist, Marcello Rubini, who roams through the nightlife of the Roman jet set. A society reporter who, despite aspiring to the life of an intellectual and writer, finds himself ensnared and inextricably linked to that glittering and superficial milieu. He is not just an observer, but an active participant, a surfer on the waves of hedonism, gossip, and ephemeral relationships.

The character of Marcello contains a dual interpretation: on the one hand, the charming viveur at ease in any environment, reveling in gossip and the large family of nocturnal creatures; on the other, the petty man, with a neglected girlfriend on the verge of suicide, an inert and apathetic man who allows himself to be carried along by events without offering the slightest resistance. His “ignavia” (inertness) is not just laziness, but a true existential paralysis, a condition that distances him from any authenticity. He is a soul adrift in a sea of superficiality, a Dostoevsky without redemption, a character who embodies the “mal de vivre” (weariness of life) of a society that, having achieved material prosperity, finds itself disoriented by its own spiritual emptiness. His constantly postponed aspiration to write a book is the emblem of unexpressed potential, suffocated by the seductive but destructive call of worldliness. Marcello is the embodiment of an existential crisis that, in those years, also found expression in Sartrean philosophy and the works of Antonioni, where alienation and the inability to communicate became central themes.

His wanderings through the Roman night will lead him to survey a gallery of diverse characters: decadent nobles who sell their titles at kitsch parties, starlets hungry for success ready to do anything for a flash, old playboys in decline clinging to an illusory youth, promiscuous and ambiguous beauties who populate drawing rooms and nightclubs. These are not mere extras, but grotesque masks of a human comedy without catharsis, a distorting mirror of the new bourgeoisie and an aristocracy that, having lost its social function, wallows in a purposeless existence, made of empty rituals and appearances. The figure of Marcello's father, who appears briefly only to disappear, accentuates the sense of an absent moral legacy, of a lost guide in a world without reference points. Each encounter, from that with young Paola, a symbol of lost innocence, to that with the writer Steiner, an apparent oasis of intellectuality that will prove fragile and tragic, is a stage in Marcello's process of disillusionment and decline.

Among these grotesque puppets of the night, he will meet a beautiful woman who will drag him into a whirlwind of events he cannot resist. Sylvia, the Swedish actress played by Anita Ekberg, is not just a diva, but an almost mythological figure, a Nordic Valkyrie descended into decadent Rome, a symbol of primitive and untainted vitality, a vital energy that Marcello cannot fully embrace, remaining captivated but also intimidated by it.

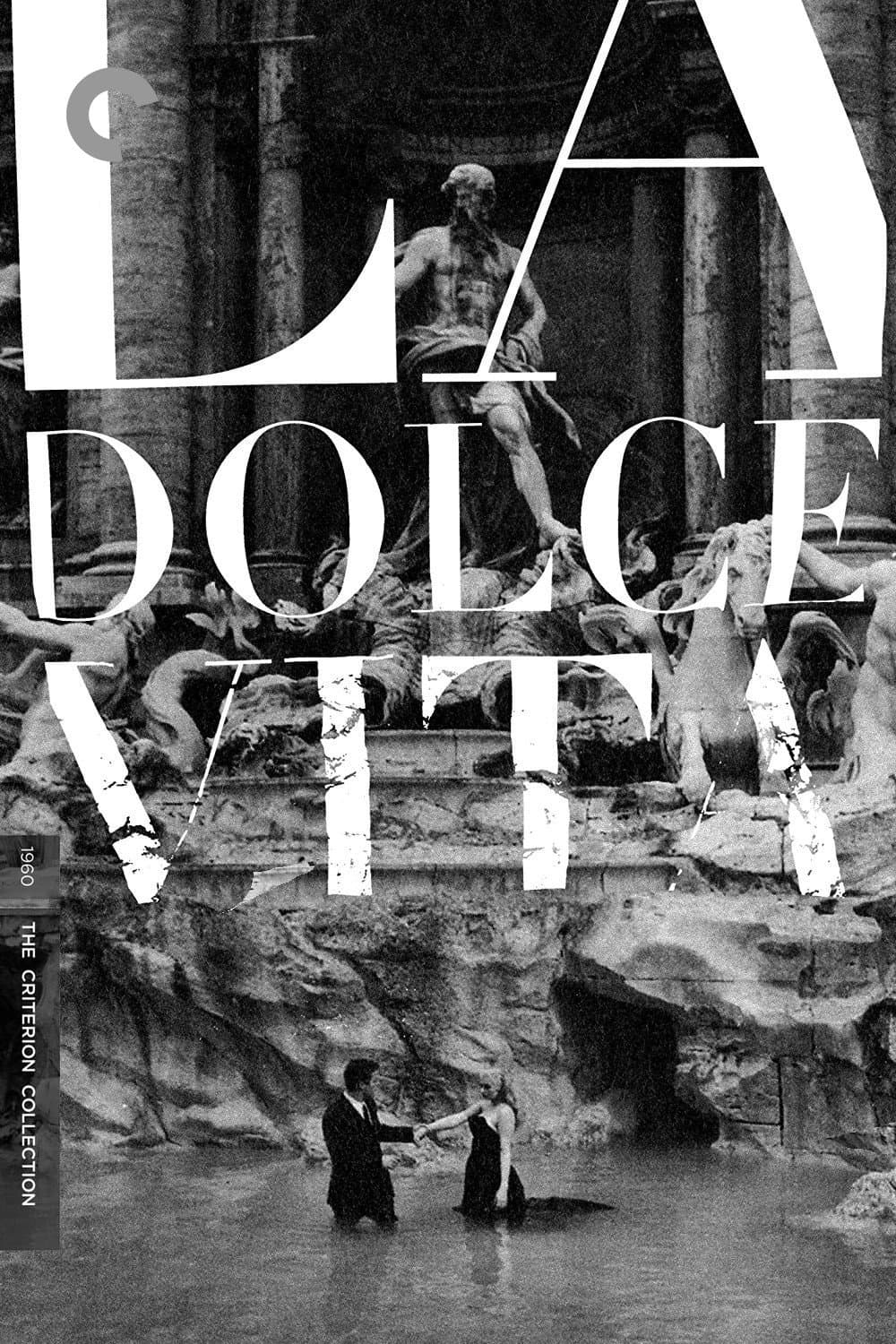

Many scenes have become part of the iconographic repertoire of every film enthusiast: the opening scene with Christ carried by helicopter over Rome's ruins and modern buildings, a fusion of sacred and profane that announces the film's tone, questioning spirituality in an era of rampant materialism; Anita Ekberg shouting to her Marcello: “Marcello come here!” as the Trevi Fountain's water bathes her face, a moment of pure sensuality and visual magic, a pagan immersion in an ephemeral utopia that will remain the pinnacle of an unfulfilled desire. But also the party sequence in the villa of the decadent nobles, a spectacle of loneliness masked as entertainment, or the final orgy at the seaside villa, the culmination of depravity and despair, where entertainment transforms into a grotesque and joyless farce. Fellini, with the collaboration of cinematographer Otello Martelli (and later Aldo Tonti), creates a sumptuous and contrasting black and white, which gives each shot an almost dreamlike aura, uniting the realism of society reporting with an increasingly surreal and introspective vision.

With this film, it has been said by many, Neorealism definitively died in Italy, and a Cinema was born that embraces dreams, melancholy, and languid memory, celebrating reality through its most evocative canons. "La Dolce Vita" does not merely represent social reality as post-war Neorealism did, but transfigures it through the filter of memory, dream, and the unconscious, shifting the focus from collective denunciation to the exploration of individual existential angst. It is a cinema that looks inward, that investigates the neuroses and emptiness of an era, effectively anticipating the French Nouvelle Vague and marking a turning point in world cinematography. Fellini invents a new language, the quintessential “Felliniesque,” made of splendor and desolation, vitality and weariness, a melancholic circus of eccentric and memorable figures that would become his trademark. The film, presented at the Cannes Film Festival and winner of the Palme d'Or, generated scandal and admiration, immediately becoming a cultural phenomenon that also gave its name to the term “paparazzo” (from the character Paparazzo, one of the photographers who follow Marcello), now entered into common lexicon.

Particular mention must be made of the stunning performance by the great Mastroianni, whom we miss more each day. His Marcello Rubini is not a character to be loved or condemned, but to be understood in his complex fragility. Mastroianni embodies with disarming naturalness the detached elegance and latent restlessness, the superficial charisma and silent despair of his character, making him an icon of an entire era. Just like the lucid genius of Federico Fellini, who with "La Dolce Vita" did not merely make a film, but sculpted an era, a sentiment, a timeless work of art that continues to question us about the nature of happiness, success, and the ultimate meaning of human existence in an increasingly disenchanted world.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...