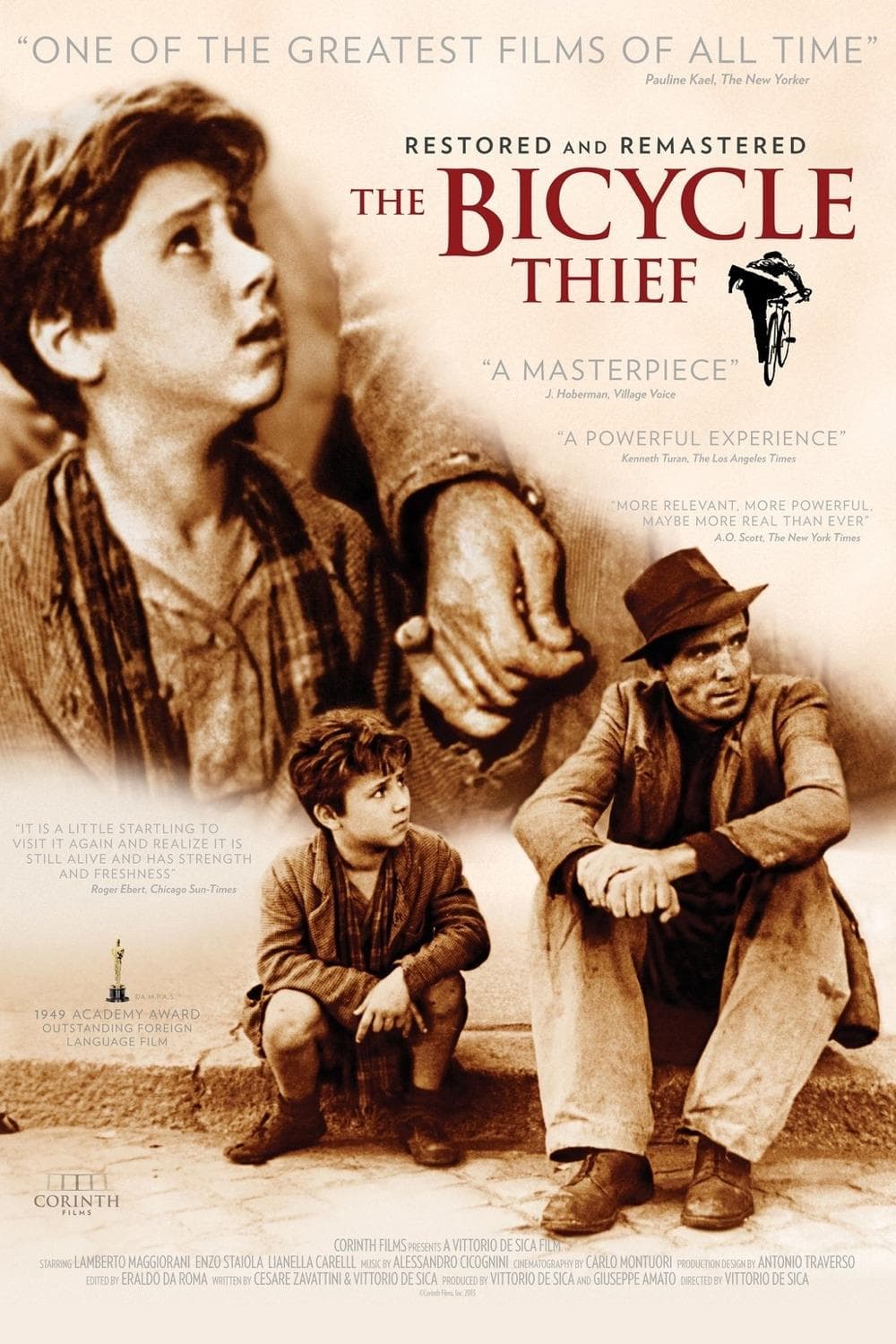

Bicycle Thieves

1948

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Vittorio De Sica emerges from the mists of the Great War and casts his profound gaze upon an Italy struggling to rediscover a real dimension after the upheaval of war. A country on its knees, whose misery had long been concealed by the bombastic rhetoric of the fascist regime, and which now, stripped of every veil, revealed itself in all its raw and disarming vulnerability. It is in this context of moral and material rubble that De Sica, with his unparalleled humanist sensibility, conceives a work that does not merely tell a story, but embodies its spirit, its very living flesh.

A man, together with his son, desperately tries to regain possession of his bicycle, stolen by unknown persons a few days earlier; the bicycle is the only tool that allowed him to carry out his work as a poster hanger. The bicycle, in Bicycle Thieves, is not a mere vehicle, not a simple tool for subsistence; it is, at the same time, the symbol of regained dignity, the promise of a future, however modest, and the tangible manifestation of a fragile hope. Its theft is not an isolated incident, but a veritable amputation of the soul, a blow struck at the beating heart of a family that had just glimpsed the possibility of rising above hunger.

An odyssey begins in post-war Rome, dense with images, characters, atmospheres, and emotions. A picaresque and harrowing journey through an urban purgatory, where the Capital itself reveals itself as a fully-fledged character: a sprawling, fascinating, and brutal entity, capable of showing flashes of ancient grandeur and, at the same time, the implacable squalor of widespread poverty. The crowded streets, the bustling markets, the tired and dignified faces of ordinary people become the backdrop for a quest that is, in reality, a descent into the abyss of human despair.

Through the man's journey, we rediscover an untamed city, eager to rise again and daily fighting against pettiness and poverty. But it is also a city that exposes the fragility of morality, where solidarity is rare and survival can lead to dehumanization. Antonio Ricci, portrayed by a magnificent Lamberto Maggiorani, a non-professional actor chosen precisely for his authenticity, traverses the circles of this hellish quest, accompanied by little Bruno, whose innocent gaze and silent suffering serve as a merciless mirror to his father's moral descent. The bond between father and son, the emotional backbone of the film, is a microcosm of the struggle to maintain integrity in a world that seems to do everything to break it.

A monument of neorealism, and broadly speaking, of Italian cinema. Bicycle Thieves is not only a key work of this movement but is its most moving and universally recognized codification. Born from the necessity of telling the truth of an exhausted Italy, neorealism radically opposed itself to propagandistic cinema and the "white telephone films" of the twenty-year fascist period. De Sica, like Rossellini and Visconti, chose the streets instead of studios, natural light instead of artificial light, and, crucially, ordinary men and women instead of stars. This was not merely an aesthetic choice, often dictated by financial constraints, but a profound ethics: a moral imperative to give the Italian people back their own image, without filters or embellishments, with a dignity that transcended misery.

A film that invented a language and codified it for the benefit of future generations. Its influence was immense, carving a deep furrow not only in Italian cinema but far beyond national borders. The French Nouvelle Vague, British Free Cinema, American independent cinema, and countless other movements were indebted to this audacious vision, which demonstrated how cinematographic art could be profoundly political and socially committed while maintaining an intense poetic quality. Its documentary approach, yet permeated with profound humanism, offered a model for a cinema capable of reflecting the complexity of real life, its ephemeral joys, and its silent tragedies.

A form of communication that arises from everyday things, the small objects that help us live, worn out by time, rendered hobbled by wear and tear. This meticulous attention to the materiality of reality is one of the film's most powerful stylistic hallmarks. Not only the bicycle, but also the worn-out clothes, the meager shared meals, the humble dwellings: every scenic element is not a mere backdrop, but a living and organic component of the narrative. These objects, "yellowed by time" like the keyboards in the song, tell the story of those who used them, bear their marks, and reflect their toil and aspirations.

A taxonomy of things placed in relation to man and his needs, his work, his small daily aspirations. De Sica's film elevates the everyday to epic, transforming a trivial search into a universal drama about human dignity and the resilience of the spirit in the face of despair. Antonio's final gesture, an act of desperation that transforms him from victim to potential perpetrator, is the culmination of this moral erosion. It is here that the film achieves its maximum tragic power, showing how misery can corrode even the most honest man, pushing him to the margins of legality. Yet, precisely in that bitter ending, in the clasp of hands between father and son, in their blending into the anonymous crowd, emerges the inexhaustible strength of the human bond, a last spark of hope in an indifferent world.

That intimate man-object relationship reminds us of a song by Guccini: "he lit up with a great joy when he approached a keyboard and preferred those a little used, those on which everyone puts their hands, those yellowed by time, a little out of tune from human ignorance and passion...". In the same way, in Bicycle Thieves, things are not mute, but speak the language of lived life, of existential precariousness. They are silent witnesses to an Italy that struggled to get back on its feet, an Italy that De Sica managed to immortalize with a sensibility that transcends time, making this film a timeless masterpiece, a cry of pain and hope that still resonates today with the intact force of great works of art. Its bitter poetry and brutal honesty remain a beacon for anyone seeking in cinema not only entertainment but a profound reflection on the human condition.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...