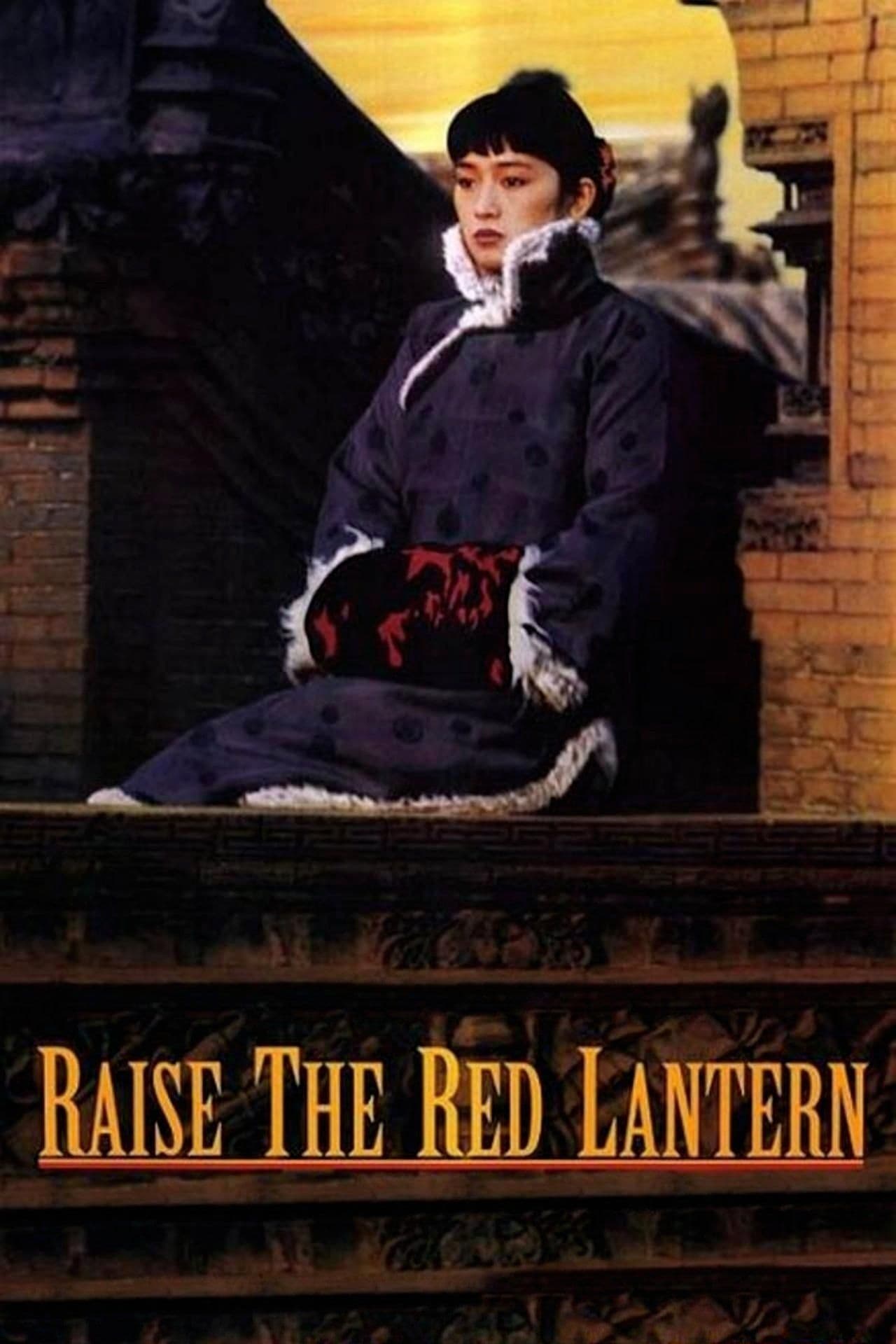

Raise the Red Lantern

1991

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

An formally pure and sublime work that aseptically surveys the customs and traditions of early 20th-century China, yielding an exceptionally vivid overall historical picture. Zhang Yimou’s camera work moves with almost surgical precision, transforming the grand residence of the Chen family into a labyrinth of imposing walls and silent courtyards, a true gilded cage where every shot is a pictorial composition, permeated by an aesthetic rigor that evokes both traditional Chinese painting and the cold majesty of brutalist architecture. The imposing complex, filmed almost entirely from a low angle, crushes the human figures, emphasizing their insignificance in the face of the patriarchal system's power. Color, particularly the vivid red of the lanterns, is never casual but is laden with stratified symbolism: passion, danger, power, but also the ineluctability of a destiny already written.

The plot centers on the character of Songlian, a girl of humble social background, who is forced to interrupt her studies to become the fourth wife of a wealthy local landowner. This forced interruption of studies is not a secondary detail; it is the first, devastating act of a progressive dispossession. Knowledge, a symbol of autonomy and critical thinking, is brutally severed in favor of a subservient role, crystallizing the tragedy of an intellect destined to rot in a meaningless existence. Her university education, rare for a woman of that era, initially makes her an outsider, a disruptive element in a pre-established balance, almost a Cassandra destined to see but unable to change her own tragic fate.

The maiden's pure world must confront and be corrupted by the sordid and cynical world of the concubines. It is a descent into the underworld of female psychology distorted by despair and competition. The first wife, elderly and resigned, concubines Yuru (the second) and Meishan (the third), a former opera singer and a woman of fragile but determined beauty, are figures who embody different facets of the same imprisonment. They are not mere antagonists, but products of a system that forces them into a fratricidal war for the only available resource: the master's attention, if not his love. Theirs are petty battles, certainly, but born of an atavistic hunger for survival and recognition, a palace "game" whose stakes are dignity and sanity.

The man will choose each night the concubine with whom to share his bed, and after the choice, a red lantern will be placed on the door of the chosen one, who must fulfill the request. This nightly ritual is the pulsating and visual heart of the film, a macabre ballet of hope and disappointment. The red lantern, a symbol of prestige and momentary supremacy, is in reality a banner of slavery, a light that illuminates the prison rather than freedom. Its lighting ritual is accompanied by a foot massage, a forced intimacy that precedes the "duty," emptying the sexual act of all affection and reducing it to a mere transaction of power. The master himself, an almost spectral figure rarely shown in the face, is the invisible Big Brother who controls the destinies of these women, making their struggle even more desperate because it is against an impalpable, omnipresent yet absent authority.

The palace intrigues are at the center of this work, making Songlian the pivot around which the entire story revolves. We witness a spiral of deceptions: Songlian's false pregnancy to gain favors, the discovery of her lie by the jealous maid Yan'er (who ironically desires her position, demonstrating how the servants are also trapped in the same logic of power), up to the chilling epilogue that sees Meishan condemned for adultery. Every maneuver is a further step in the corruption of Songlian's soul, who transforms from victim to executioner, learning too well the rules of the game she initially detested. Her presumed "purity" progressively unravels, a victim of her own intelligence which, instead of saving her, makes her more acute in perceiving her misery and in attempting survival strategies, only to end up annihilated by them.

It is truly difficult to follow all the plots that courtiers and concubines weave, but Songlian's immaculate purity seems to remain a constant in the narrative, almost a longed-for haven amidst the swirl of events. However, it is precisely here that Zhang Yimou's genius reveals itself most ruthless: Songlian does not maintain her purity. She is stained, corrupted, and finally annihilated by the system. Her mental collapse at the end of the film, which sees her wandering like a ghost among the mansion's walls, is not the preservation of integrity, but its total dissolution, the ultimate, tragic consequence of a denied existence. Her figure is not a beacon of hope, but a terrifying warning about the destructiveness of oppressive power and the futility of individual resistance against such a monolithic structure. The film closes with the arrival of a new, very young concubine, indicating the ineluctable cyclicity and permanence of these dynamics.

A magnificent film by Zhang Yimou, a director who has opened the doors to China's vast culture, revealing enlightened glimpses into a society interwoven with millennia-old rituals. Part of the so-called "Fifth Generation" of Chinese directors, Zhang Yimou, with works like Red Sorghum, Ju Dou, and this masterpiece, has been able to infuse visual beauty with pungent social criticism, often clashing with regime censorship. Here, his formal aesthetic merges with a psychological depth reminiscent of great classical melodramas, but with a detached coldness that elevates them to the level of an anthropological study. Gong Li's performance, muse and life partner of the director at the time, is magnetic: her Songlian is an explosion of pride, vulnerability, and contained despair, capable of expressing entire inner worlds with a single gaze. "Raise the Red Lantern" is not just a film about the female condition or early 20th-century China; it is a universal allegory about power, oppression, and the destruction of the individual in the name of traditions and social structures that, despite their apparent magnificence, conceal an intrinsic brutality. It is a work that, like few others, manages to be both a meticulous study of customs and a harrowing human tragedy.

Main Actors

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...