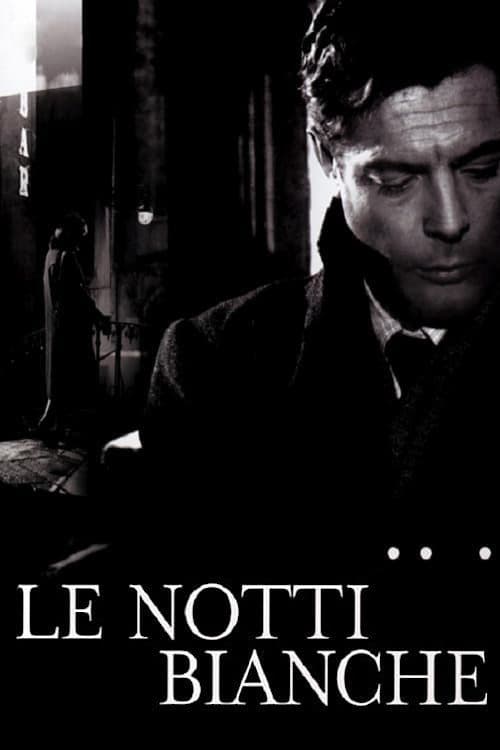

Le Notti Bianche

1957

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A polished and hypnotic Visconti directs this Venetian canvas, portraying it as a long dream, or perhaps, more precisely, as a lucid waking delirium. It is a Venice that is not merely a geographical backdrop, but a character in its own right, a tangle of canals and bridges that becomes almost a projection of the protagonists' unconscious, a labyrinth from which the soul cannot escape. His direction here is a symphony of nuances, a meticulous mise-en-scène that transforms realism into an almost ethereal fabric, suspended between the tangibility of stones and the impalpability of illusions.

On this dreamlike stage, Mastroianni meets a woman in tears and becomes her devoted escort for three consecutive nights, leading her through the Venetian night and admiring her icy beauty. His character, the quintessential dreamer borrowed from Dostoevsky's pen, is the embodiment of an almost anachronistic sensibility, an incurable romantic struggling in a world without easy answers. Mastroianni, with his restrained vulnerability and his melancholy gaze, creates an archetype destined to define his subsequent career. Natalia, played by a Maria Schell of sublime fragility, is less a flesh-and-blood person than an idea, a projection of desire, whose "icy beauty" embodies the unattainability of the romantic ideal, a spectral figure suspended between an idealized past and a present she cannot grasp.

On the last night, it begins to snow, a chilling omen that permeates the air, not just physically, but emotionally, heralding the unraveling of illusions.

Visconti traps his characters (three excellent acting performances: Mastroianni, Marais, and Schell) within a microcosm made up of canals, bridges, and calli, a claustrophobic setting in which they struggle as if in an impalpable prison. It is essential to emphasize that this Venice is not the authentic city, but a meticulous and evocative reconstruction in the Cinecittà studios (evoking, with poetic license, Dostoevsky's Livorno novella but transfiguring it into the Venetian imaginary). This artificiality is not a limitation, but a strength: it amplifies the sensation of a chamber drama, of an existence suspended in a limbo of artistic creation, where reality is filtered and sublimated. The canals become arteries of silent anguish, the bridges barriers between hope and despair, the calli a labyrinth from which one cannot exit, not because there is no physical way out, but because the soul is imprisoned in a repetitive cycle. Jean Marais, whose character is an absence rather than a tangible presence for much of the narrative, exerts a ghostly influence, embodying the overwhelming weight of fidelity and memory that holds Natalia captive to a past love.

The film is a series of short walks, chases, escape attempts, always frustrated, always zero-sum. Every step, every pang of the soul, brings the characters back to the starting point, in a melancholy dance of ephemeral hopes and bitter disappointments. It is a ballet of missed gestures, of unspoken words, an exhausting search for an authentic human connection that proves elusive, like the shadow of a dream upon waking. The episodic and repetitive structure underlines the futility of every effort, the cyclical nature of unfulfilled desire.

Filmed in a neorealist style – or rather, with a transfigured neorealism, a "neorealism of the soul" that abandons social chronicle to explore psychological depths – the film offers its characters a single strange moment of escape from their nocturnal obsessions: a subversive scene in a ballroom that clouds the atmosphere, rendering it languid, sensual. This sequence is a cathartic and almost violent explosion in a work otherwise dominated by controlled melancholy. The music, the frantic movement of bodies, the desperate vulnerability surfacing in the contorted faces, are a moment of raw, almost painful, vitality. It is an unexpected rupture of emotional reality that breaks the spell of the dream, revealing the intensity of desire and the fragility of illusions, a sensuality that is not erotic but the expression of compressed anguish finding release in an ephemeral liberation. Visconti, though he came from the ranks of the more orthodox neorealism, here builds a bridge towards his subsequent works, more baroque and introspective, where psychological analysis prevails over social documentation.

Then the snow falls, and with it a cold despair upon human illusions. The snow is not merely a meteorological element, but a powerful symbol: a white and pure blanket that, paradoxically, brings no solace but a sense of final desolation, of crystalline purity that seals the characters' destiny in their solitude. It puts an end to the "white nights," that period of twilight light and fluid boundary between day and night, between dream and reality, bringing with it the harsh and unequivocal clarity of a frigid dawn.

It is a film that anatomically dissects the element of "love," performing a meticulous transposition of the stream of consciousness that arises from it. Love here is not a feeling that materializes, but an obsession, an illusion that the self constructs to escape its own solitude, an echo of Dostoevsky's most tormented pages on the nature of "dreamers." The stream of consciousness manifests itself in eloquent silences, in gazes laden with unspoken words, in fleeting expressions that betray complex inner worlds. Visconti digs into the pathology of unrequited desire, into the cruel beauty of waiting, and into the mask that man wears to protect his fragile heart. It is not the story of a love but the radiograph of a soul that loves self-destructively, incapable of grasping reality and condemned to chase phantoms.

A sensual and disquieting work that lingers long in the memory, a Viscontian elegy on the intrinsic melancholy of existence. Its lasting power resides in its ability to transform a simple story of unrequited love into a profound meditation on memory, on hope, and on the poignant beauty of what can never be. It is a rare gem in Visconti's filmography, a perfect bridge between his neorealist rigor and his subsequent, sumptuous exploration of decay and beauty in disintegration. A testament to the fact that the most refined prisons are often those we build with the invisible threads of our heart.

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...