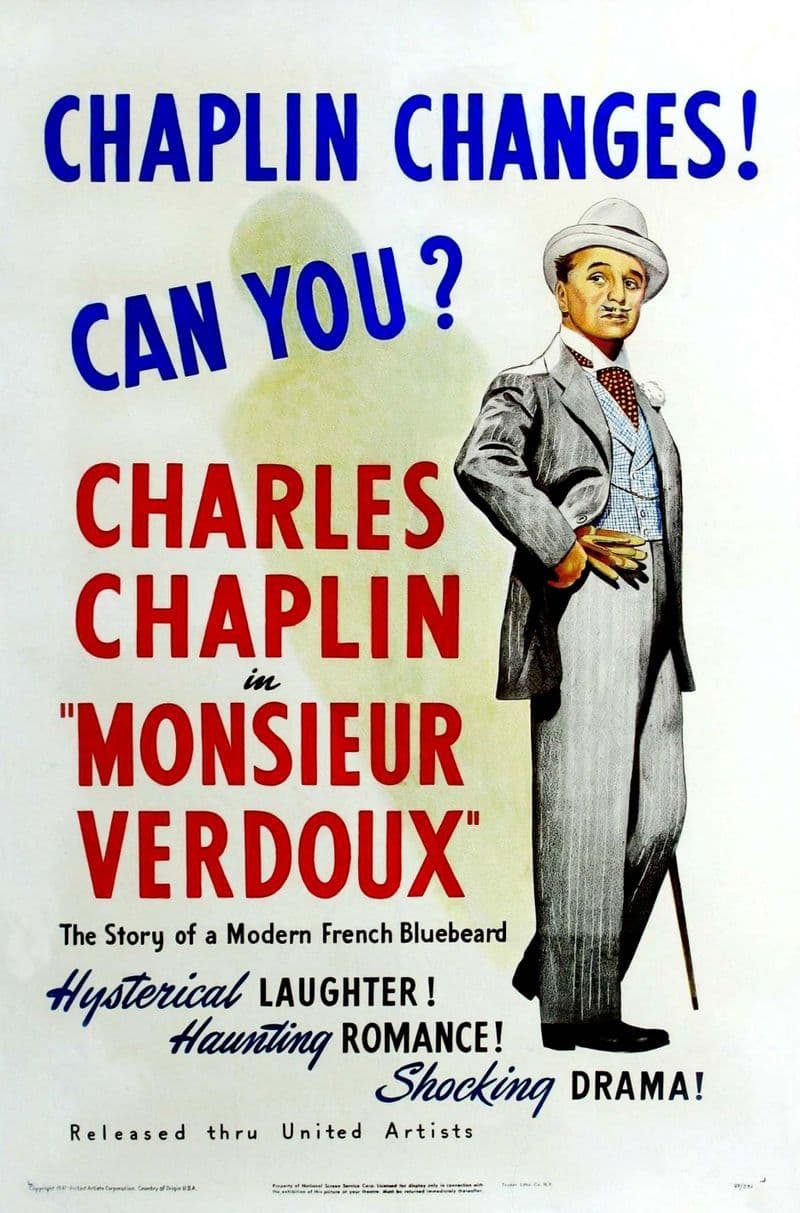

Monsieur Verdoux

1947

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Based on a story by Orson Welles, Chaplin wrote, directed, starred in, and produced a wonderful portrait of a petty bourgeois who transforms into a cunning murderer out of necessity. The film's genesis is, in itself, revealing: Welles had envisioned a documentary about Henri Désiré Landru, the "Bluebeard of Gambais," but the project was shelved, only to be reborn under the hand of Chaplin's genius. What could have been a mere true crime story thus transformed into a biting social satire and an unprecedented and audacious stylistic turn for the artist. Chaplin's approach to the theme is delightfully oblique: a narrative that alternates noir nuances with an ironic and poetic progression, establishing itself as the first great black comedy in cinema history. A pioneering black comedy, capable of anticipating by years the more macabre and mocking veins that would later permeate Stanley Kubrick's cinema with his Dr. Strangelove or the moral idiosyncrasies of Robert Hamer's Kind Hearts and Coronets, released just a year later and often mistakenly credited as the progenitor of the genre. But it is in Chaplin that we find for the first time that disenchanted cheerfulness in recounting horror, a true act of artistic courage that sanctioned the definitive and sensational abandonment of the Tramp character, a gesture that, understandably, disoriented and irritated a significant portion of the public and critics.

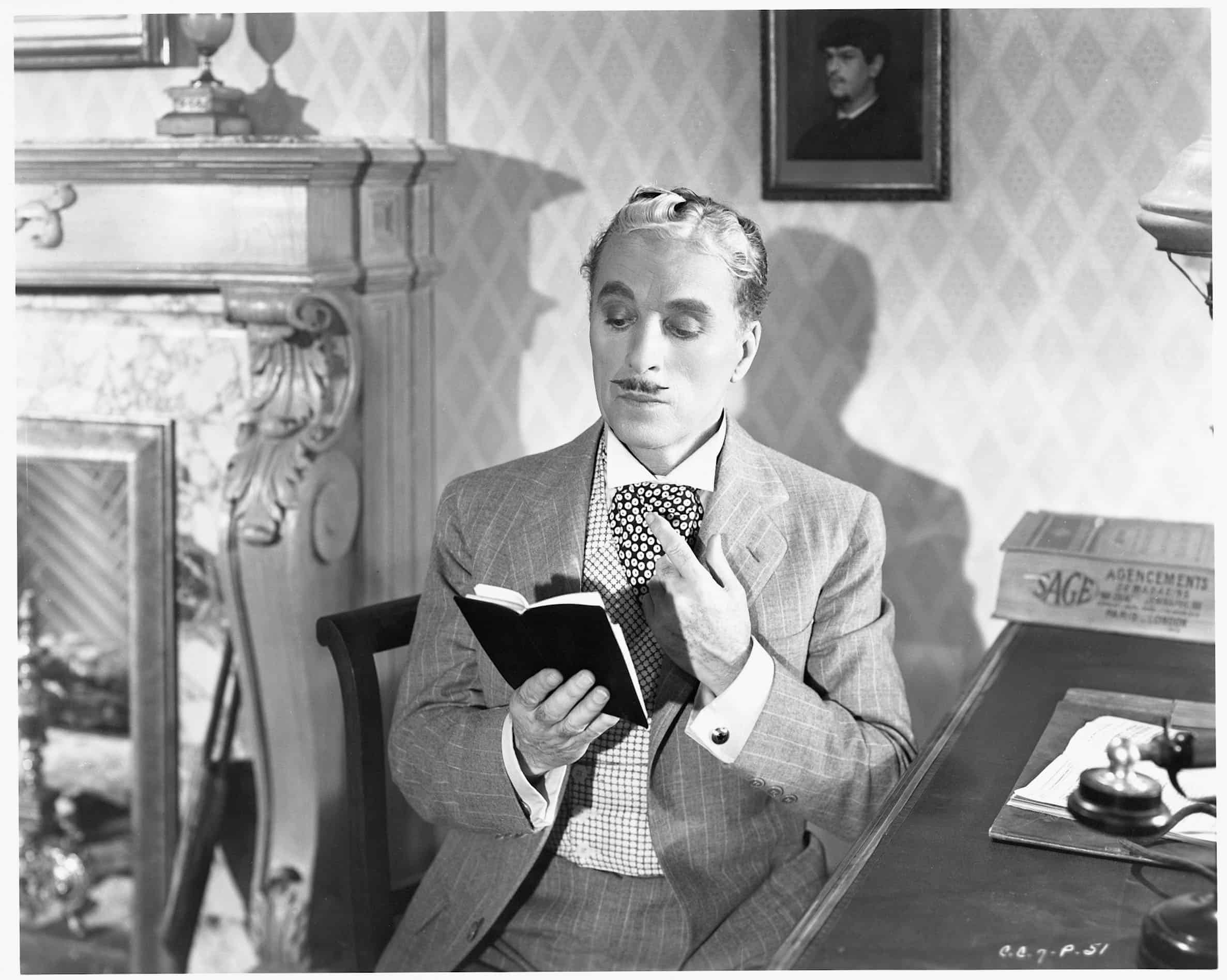

Monsieur Verdoux, a banker laid off due to the economic crisis that hit France in the 1930s in the wake of the Great Depression, must reinvent himself to support his ailing wife and infant son. It is New Deal America reflected in mass-unemployment France, a context of deprivation where bourgeois respectability is the first victim of a relentless economic system. Verdoux, a man of order and precise calculations, is not a born criminal, but an entrepreneur of evil, a perverse capitalist who applies the same logics of efficiency and profit from traditional finance to the art of murder. He manages to reinvent himself as an antique dealer, but in reality, the work yields little. He then decides to ensnare elderly wealthy ladies, marry them, and then pocket their inheritances. To impress these gentle ladies, Verdoux uses his undeniable charm, bolstered by a refined elegance that he deploys with enviable naturalness, almost as if his activity were not atrocity but a meticulous work of seduction and persuasion. His activity becomes tireless, moving from one altar to another, from one marital bed to another, and from one funeral to another. A macabre ballet of hypocrisy and necessity, where every gesture is calculated with the precision of a watchmaker, and where death becomes the mechanism of a cruelly efficient money-making machine. Just when he manages to accumulate a decent sum that would allow him a comfortable life, he is identified by the relatives of one of his victims and almost arrested. Having narrowly escaped the guillotine, after family setbacks, he will spontaneously decide to turn himself in to the police.

Verdoux, a philosopher and poet assassin, cannot but fascinate the viewer, who finds in him what they never found in Chaplin's characters: that malicious inclination that leads him to lose himself in the dark pleasure of crime, almost a poison-like addiction that prompts the audience to root for this polite and lethal man. It is not brute violence that drives him, but a distorted logic of survival and a ruthless analysis of the society around him. His charm lies precisely in this contradiction, in this abyss between the elegance of his manners and the atrocity of his actions. The ethics of crime undergo a semantic subversion of meaning through a rhetorical sagacity that stuns and enchants. Chaplin does not justify Verdoux, but positions him as a distorting mirror of the world's contradictions, an anti-hero who, in his cynicism, reveals the hypocrisies of the system. In this sense, his figure aligns with that of other literary characters who, though immersed in criminality, are vehicles of a broader social critique, such as Dostoevsky's Raskolnikov or Camus's Meursault, albeit with very different intentions and tones.

Memorable in this regard is Verdoux's final monologue, where, addressing the judges about to condemn him to death, he utters these immortal words: "However sparing the Public Prosecutor has been with his compliments, he has nevertheless admitted that I have a brain. Merci, Monsieur. I have. And for thirty-five years I used it honestly. After that, no one wanted it anymore. So, I used it on my own behalf. If we then talk about massacres, do we not have authoritative examples? All over the world, increasingly perfect devices are manufactured for the mass extermination of people, and how many innocent women and children have been killed mercilessly, and perhaps more scientifically! Eh, as an exterminator, I am a pathetic amateur, by comparison." This epilogue is not only a brilliant exposition of Verdoux's twisted logic but a veritable Chaplinian manifesto against the hypocrisy of war and institutional violence, themes the actor-director had already addressed more directly in The Great Dictator. Here, however, the accusation is more subtle and incisive, conveyed through the voice of a murderer who, though condemned, rises as a moral judge of a society that condemns petty crime but extols mass slaughter. The political resonance of these words, combined with the film's stylistic shift, contributed significantly to the ostracism Chaplin suffered in the United States during the McCarthy era, where his critical humanism was interpreted as subversive. Monsieur Verdoux, released in 1947, thus became a prophetic film not only for its content but also for the fate of its creator, who was forced into exile a few years later. An audacious, uncomfortable, and necessary masterpiece that continues to challenge us about the grey areas of human ethics and the violence inherent in civilization.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...