Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

1939

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A film of dual significance, almost oxymoronic in its inherent harmony, this one by Frank Capra: political significance, with the audacious attempt to dismantle not only the demagogic veneer of the American dream but to question its very moral substance through a biting indictment of an infected and corrupt political system, a well-oiled machine of interests and compromises that threatens democratic foundations; social significance, with its incisive portrayal of a perverse metropolis filled with social climbers, opportunists, and lobbyists where the most abject cynicism reigns supreme, eroding every ideal, strikingly contrasted with the poignant lyricism of the pristine innocence, almost evangelical purity, and unwavering moral rectitude of those from the distant provinces, an emblem of a purer and more authentic America, perhaps idealized but no less powerful in its resonance.

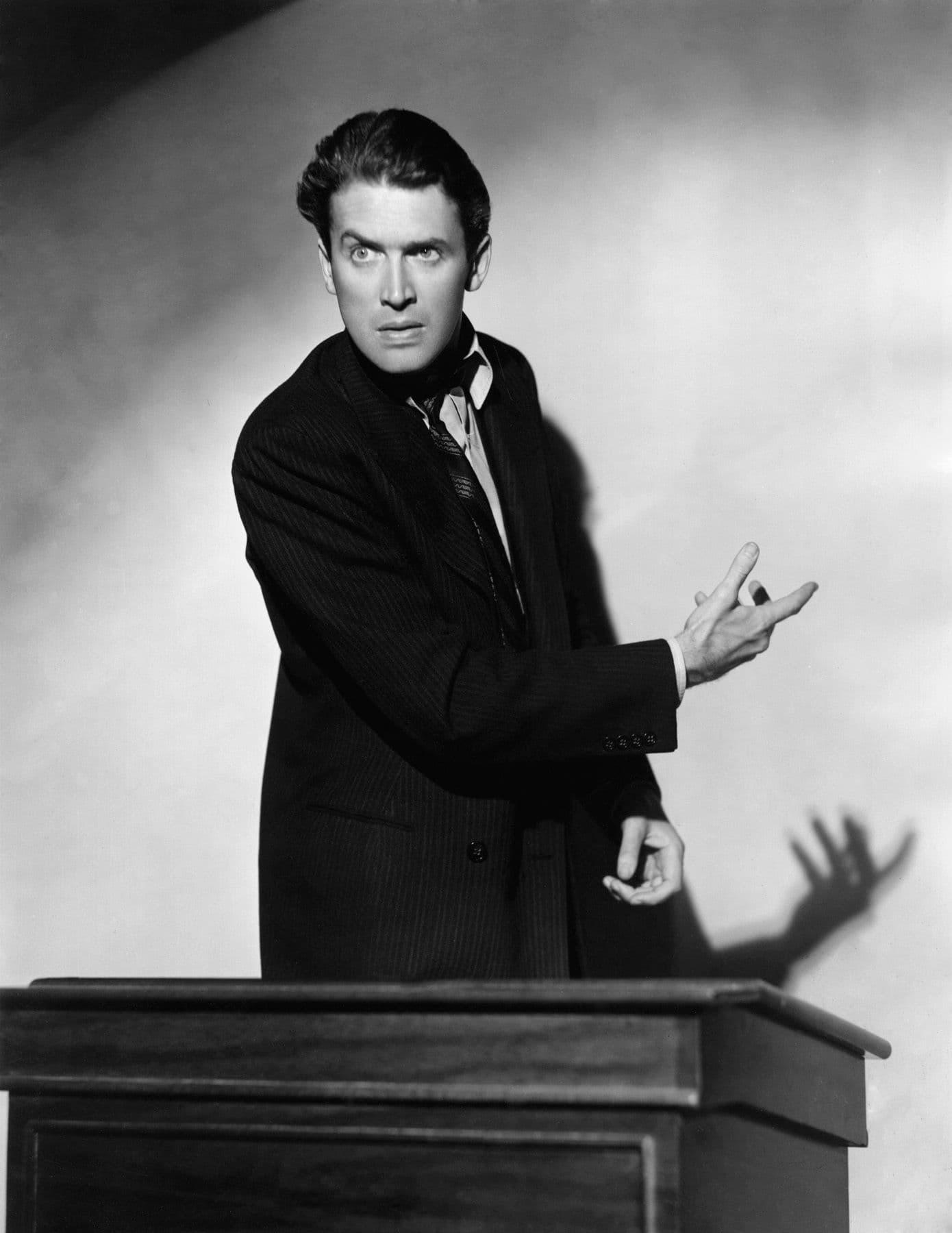

James Stewart, in the role of Jefferson Smith, delivers a memorable performance that not only embodies an ideal but imbues it with surprising psychological complexity. His Smith is an archetype, certainly, but also a man of flesh and blood, capable of passing from boundless enthusiasm to searing disillusionment, only to rise again with almost superhuman tenacity. His acting, marked by nervous tics, uncertain stutters, and a gaze at once naive and penetrating, lends the character a credibility and humanity that transcend mere portrayal, cementing the figure of the reluctant, profoundly American hero, destined to become a trademark of his career and a benchmark in the collective imagination.

Jefferson Smith, a young and idealistic Boy Scout leader, an emblematic figure of an America of simple and pure values, is catapulted into the Capital to replace a deceased senator. Initially enthusiastic to serve his country with the same devotion with which he guided his young pupils, Smith goes to Washington with his mind brimming with hope and a heart pulsating with good intentions, convinced that politics is the noblest arena for the common good. But his epiphany is brutal: he soon clashes with the cynical and corrupt reality of the Senate, a melting pot of hidden interests where democratic rhetoric masks a dense web of intrigues, and where politicians, led by the charismatic but devious Senator Taylor (a memorable Claude Rains, capable of endowing his character with an ambiguous depth and inner conflict that elevates him beyond a mere villain), are more interested in their personal affairs and the perpetuation of their power than in the welfare of citizens. Smith, with his disarming naivety and adamant honesty, becomes an easily manipulated pawn, exploited and deceived by Taylor, who involves him in a shady real estate speculation deal for the construction of a dam. When Smith's innocence clashes with the murky truth and his conscience compels him to strenuously oppose the corrupt bill, he inevitably becomes the victim of a ruthless smear campaign orchestrated with cynical mastery by Taylor and his loyal allies. Isolated, ridiculed, and delegitimized in the eyes of public opinion and his own colleagues, Smith seems destined for inevitable defeat, a lone David against a sprawling Goliath.

But hope, like a flower blossoming in the moral desert, is reborn thanks to the unexpected help of his cynical but golden-hearted secretary, Clarissa Saunders (a vibrant Jean Arthur, whose narrative arc is as crucial as Smith's), and a handful of young journalists still able to distinguish truth from lies. Smith, tempered by adversity but not broken, decides to resist to his last breath and fight for the truth with the only weapon left to him: his words. He thus undertakes a monumental act of filibustering in the Senate, an epic and harrowing undertaking in which, speaking non-stop for hours on end, under the gaze of cameras and the pressure of a hostile press, he attempts to awaken dormant consciences and expose corruption. It is a scene of rare emotional and dramatic power, a masterful acting tour de force that showcases the character's extraordinary physical and moral resilience, until, exhausted by fatigue but not in spirit, he collapses to the ground, a living symbol of a titanic struggle. But his battle was not in vain: his unyielding integrity and indomitable will for truth shake the foundations of the system. Senator Taylor, a man not without complexity, tormented by remorse and the awareness of the moral abyss into which he has fallen, confesses his guilt and resigns, but not before attempting suicide in an extreme gesture of redemption. Smith, welcomed as a hero by the nation and cleared of all infamy, demonstrated with his solitary, desperate resistance that even one man, armed with ideals and an iron will, can make a difference, can crack the monolith of corrupt power and rekindle the flame of democracy.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is not just a film; it is a cinematic monument that has had an indelible impact on American culture and a pivotal role in the history of cinema. Made in the crucial year 1939, on the eve of World War II, in an era of escalating international tensions and tangible threats from totalitarianisms (Nazism, Fascism, Stalinism) that promised order at the expense of freedom, the film stands as a passionate and vibrant defense of democracy, an anthem to the resilience of the American spirit, and a warning against the ever-present dangers of authoritarianism and moral corruption. Its reception was controversial: though beloved by the public, it greatly irritated the political establishment in Washington, which accused it of defeatism and of denigrating institutions, failing to grasp, or perhaps refusing to grasp, its profound patriotic and reformist essence.

Capra, with his clear, accessible, yet profoundly engaging direction, once again demonstrates his genius in creating a perfect balance between comedy, drama, and pathos, a trademark of his cinema, often dubbed "Capra-esque" or, with some superficiality, "Capra-corn." But behind the apparent optimism always lies an acute social critique. Through close-ups that delve into the characters' souls, incisive dialogues, and emblematic situations that serve as powerful metaphors, the director masterfully reveals the intrinsic contradictions and fragilities of the human spirit, showing how even the most powerful and seemingly upright individuals can be seduced and corrupted by the mirage of power. His staging is a skillful orchestration of light and shadow, of claustrophobic spaces and imposing architectures (the majesty of the Senate dwarfing the individual), of driving rhythms and moments of quiet reflection.

A remarkable work not only in its fluid narrative but above all in its comprehensive characterization of each person, from the smallest to the largest. Capra's hypertrophic gaze functions like an implacable microscope, laying bare complex personalities and multifaceted psychological traits, revealing the most recondite motivations behind actions. His great legacy, which intrinsically connects it to his other masterpieces like Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and It's a Wonderful Life, is a film that fervently celebrates the indomitable strength of individual conscience, the cathartic power of truth, and the inescapable necessity of active citizen participation in political life, in an era where such engagement is perhaps more crucial than ever. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is not just a timeless classic; it is an ethical and artistic benchmark for all who stubbornly and rightfully believe in cinema's transformative power to inspire, to question, and, ultimately, to change the world, reminding us that democracy is a fragile good, to be defended with the same tenacity as Senator Smith.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...