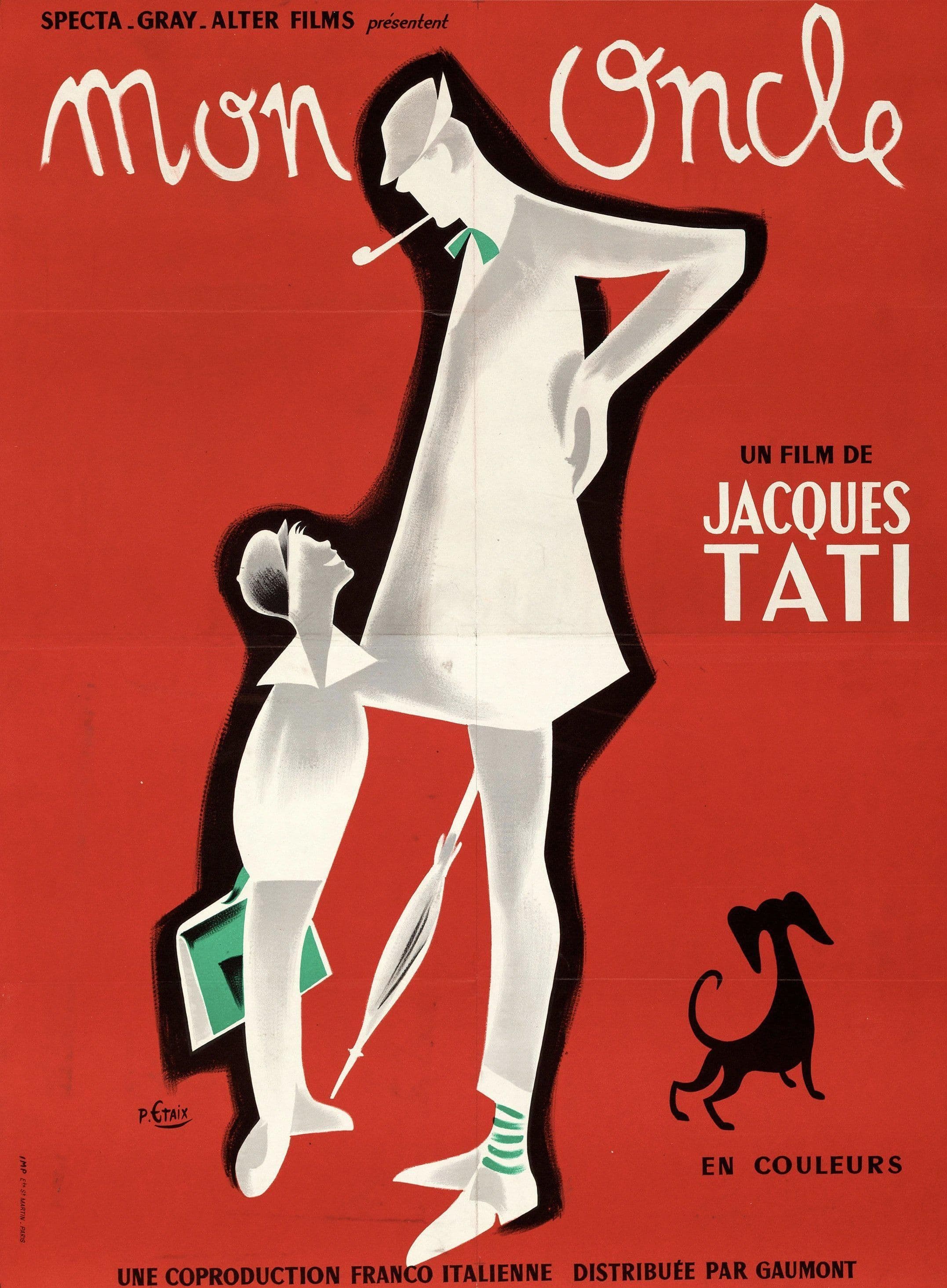

My Uncle

1958

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

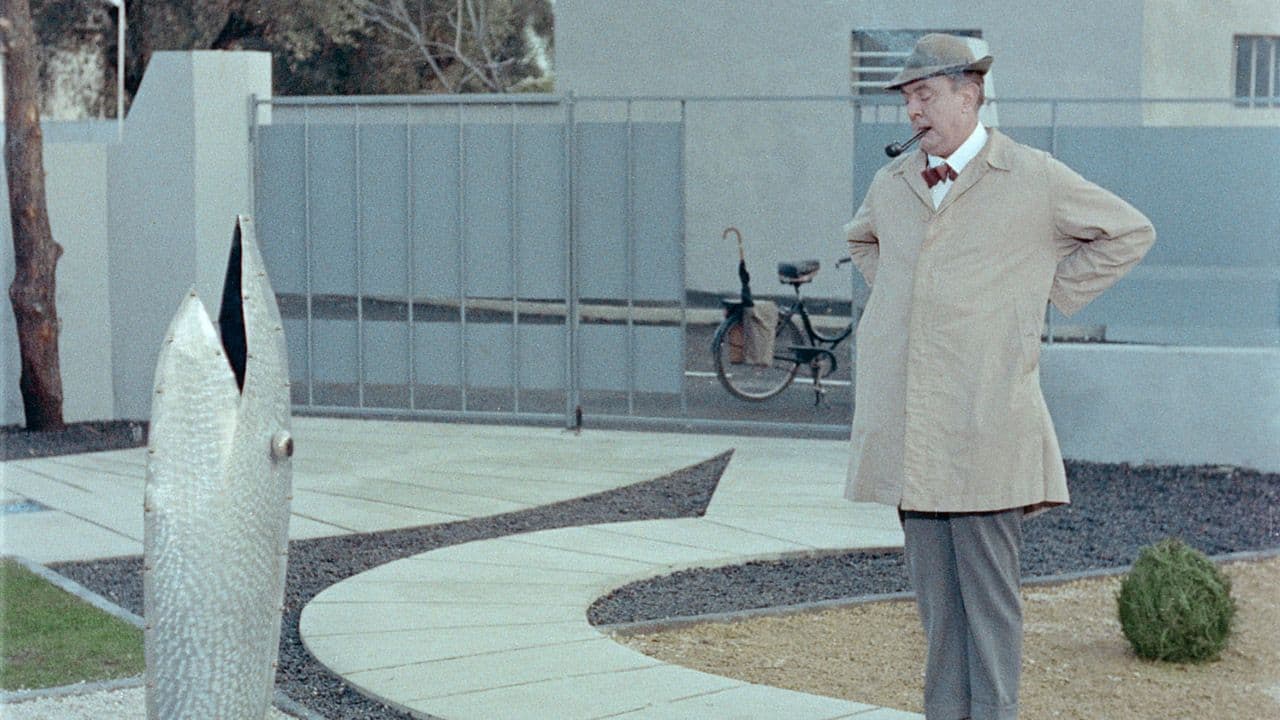

Director

Five years after his appearance in Le Vacanze di Monsieur Hulot (1953), the ineffable Monsieur Hulot returns in this fourth, and perhaps most ambitious, film by Jacques Tati. Presented at Cannes in May 1958, where it won the Special Jury Prize, Mon Oncle immediately became an instant classic, a work revered by generations of film buffs who loved its graceful comedy, free of noise and vulgarity. But to relegate it to a simple comedy, however elegant, would be a huge critical mistake. In addition to this aspect of absolute lightness, the film is appreciated for a series of themes and ideas that elevate it to a masterpiece. First and foremost is the theme of criticism of modernity, the stigmatization of the frenetic and preordained rhythms of a prefabricated society that we had already found in Chaplin's Modern Times. However, while Chaplin's Charlot fought desperately against the dehumanizing industrial machine, Tati's Hulot finds himself facing a more subtle and insidious enemy: the tyranny of design and domestic comfort. The criticism here is more subtle and fierce, driven by the winds of gentle irony. Tati highlights the most grotesque contradictions of modernism, its claim to efficiency that translates into an absurd complication of life. He paints a picture of a bourgeoisie stuck in the rut of their work, compressed into dialogues devoid of any humanity, overwhelmed by an anxiety for progress and technology that devastates all social interaction to the jarring sound of improbable buzzers and multifunction switches. All this is corroborated by scenic devices that make this film a true cornerstone of satirical cinema: the electric garage door activated by photoelectric cells that imprisons the Arpel couple; the gushing of a fish-shaped fountain that is only turned on when guests are present and, after being misdirected by Hulot, sprays mud and oil; the portholes of the Arpels' hypermodern villa, which look like giant eyes spying on Hulot's furtive movements at night, with the pupils formed by the heads of the two Arpels peering through the windows.

The Arpels are proud of their hypermodern mansion, Villa Arpel, equipped with every comfort, ultra-geometric and minimalist, plasticized and automated. This is not just a house, it is an architectural thesis, a brilliant and ruthless parody of the modernism of the International Style and the housing utopias of Le Corbusier. It is a “machine for living” that forgot to include human beings in the instructions. This techno-monster seems to challenge the old houses of a Paris still imprisoned in the post-war period, dusty and decadent neighborhoods that are actually bursting with vitality, with people greeting each other on the street, arguing animatedly, and experiencing the city as a genuine place of encounter and aggregation. Mrs. Arpel's brother, Monsieur Hulot, is a quirky middle-aged gentleman with his eternal raincoat and pipe, who lives in a penthouse nestled in one of these old neighborhoods. His apartment is located on the roof of an old building, which he can only reach by climbing and passing through dozens of rooms, in a sort of obstacle course that the viewer follows with rapt attention through a fixed, almost theatrical shot of the building, while Hulot appears in every nook and cranny, window, hallway, and corridor until he reaches his coveted destination. That is not a house, it is a vertical village, an ecosystem of human interactions. The two houses are immediately placed in stark contrast; it is ultimately the dichotomy of a city that coexists between past and future. Hulot is the uncle of Gérard, the Arpel's young son, whom he often picks up to take to school, racing around on his old motorbike. The child loves his uncle and those fantastic deviations from an otherwise predetermined and perfect life. Their bond is a silent and joyful conspiracy against the adult world, a world where even the garden is a geometric path on which it is forbidden to walk. But the Arpels don't like Hulot's lifestyle and try in every way to bring him to his senses, to ‘normalize’ him, by finding him a wife or a job in the Pater Familias' company, which, ironically, deals in plastic derivatives.

Lightness and irony, as we have said, but also smiles that start out silent and furtive and become boisterous in an intelligent, allegorical, and entertaining work. Jacques Tati confirms himself as the father of a cinema that, taking the ancient Latin adage “Castigat ridendo mores” literally, puts into practice an almost silent art made of physicality and naturalness. His comedy is architectural and democratic. Unlike Chaplin, who dominated the scene, Tati rarely uses close-ups. He prefers wide shots, almost tableaux vivants, where Hulot is just one of the elements at play. He entrusts the viewer with the task of exploring the image, of discovering the gag unfolding in a corner of the screen. He is the heir to Buster Keaton in the way his comedy arises from the clash between an imperturbable individual and a complex, mechanized environment, but he replaces Keaton's dangerous chaos with gentle, dysfunctional absurdity. A film that still entertains and fascinates viewers today.

Tati's vis comique, although rooted in the tradition of silent cinema, possesses a sensibility that we could define, with a little intellectual daring, as postmodern. The humor in Mio Zio stems from a deep distrust of the grand narrative of Progress. Tati stages the failure of the modernist utopia: the ultra-technological kitchen is uncomfortable and produces food with unnatural colors, the designer living room is a place where one cannot relax, and automated life is a sequence of small, irritating malfunctions. It is a gentle but relentless deconstruction of the myth of technological salvation. Furthermore, the film is obsessed with surfaces, a theme dear to postmodernism. The Arpels are defined not by what they are, but by what they own and how they appear. Their life is a performance of modernity for their guests. Tati uses sound ingeniously to emphasize this artificiality: the modern world is a concert of mechanical buzzes, clicks, and hisses, while Hulot's world is full of human sounds, chirps, and music. My Uncle is, ultimately, a work of boundless sweetness and intelligence, a gentle warning against our tendency to confuse progress with happiness.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...