Nazarin

1959

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Buñuel stages a novel by the Spanish writer Benito Pérez Galdós and perfectly transfigures its most intimate meaning, presenting it to a spectator captivated by the lucid flow of images. The Buñuelian adaptation is not limited to a mere transposition, but rather performs a true distillation of the Galdosian essence – which often manifested as veiled social and anti-clerical criticism – only to then inject it with his own corrosive venom, typical of an intellectual and surrealist sensibility. While Galdós, despite his realist acumen, maintained a certain distance, Buñuel plunges into the material, dismantling the foundations of Christian faith and charity with the precision of a surgeon and the disenchanted irony of a skeptical philosopher. It is a "transfiguration" that, in some respects, anticipates the ethical and spiritual ruptures that the Spanish director would explore with even greater virulence in subsequent works like the famous Viridiana, which is also a relentless examination of the vanity of altruism in an irrevocably corrupt world.

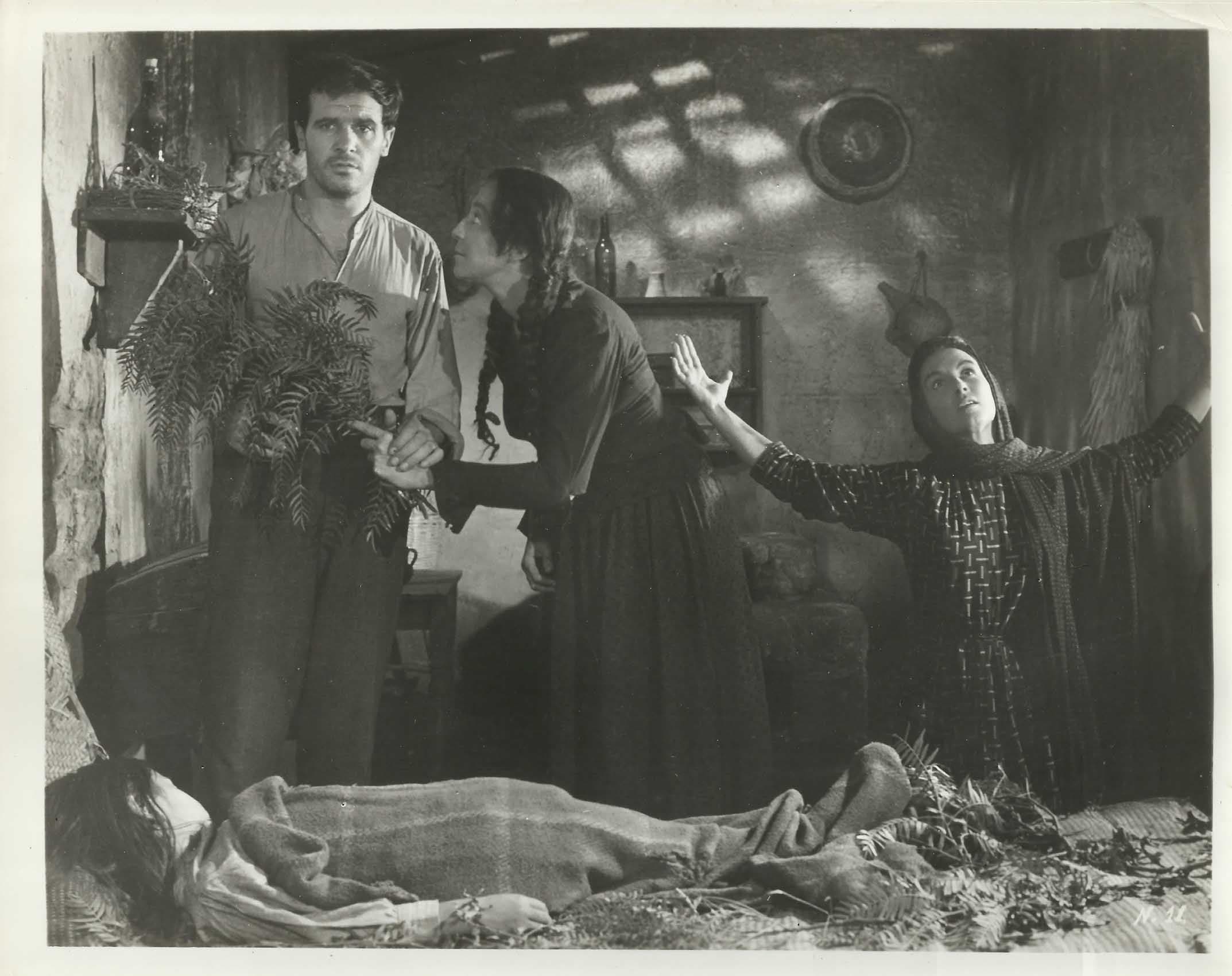

The story centers on the figure of Father Nazario, a Saint Francis ante litteram, who brings his mission of mercy to the humblest people in the landowning Mexico of Porfirio Diaz. The choice of historical context is not accidental: late 19th-century Mexico, under Diaz's authoritarian regime, was a powder keg of social inequalities, where the most abject misery coexisted with the ostentation of an ecclesiastical and civil power often indifferent to or complicit in oppression. In this landscape of suffering and pre-revolution, Father Nazario is not merely a man of faith, but an archetype, an almost pure incarnation of evangelical doctrine, who seeks to literally apply Christian precepts in an environment that is not only unreceptive but actively rejects them, like a foreign body in an infected organism. His naivety or, perhaps, his radical spiritual honesty, makes him an easy target for human wickedness and the inherent cruelty of the system.

The friar dedicates himself to others by applying the words of Christ, but every one of his efforts is rendered futile by a series of events that turn his piety and altruism against him. This series of misfortunes is not the result of mere bad luck, but the expression of a universal and ruthless law, which seems to want to demonstrate the ineffectiveness, or even the harmfulness, of absolute goodness in a world relativized by evil. Every act of charity turns into a misunderstanding, every attempt to help backfires into an accusation, every sacrifice generates ingratitude or worse, a further fall. From the prostitute who sets his room on fire and forces him to flee, to the bandits who rob and humiliate him, to the woman who unjustly accuses him of murder, his via crucis is paved not with nails, but with distorted intentions and perverse outcomes. It is the triumph of reality over the purity of the ideal, a theme Buñuel would explore throughout almost his entire filmography, unmasking bourgeois hypocrisy and the futility of dogmatism.

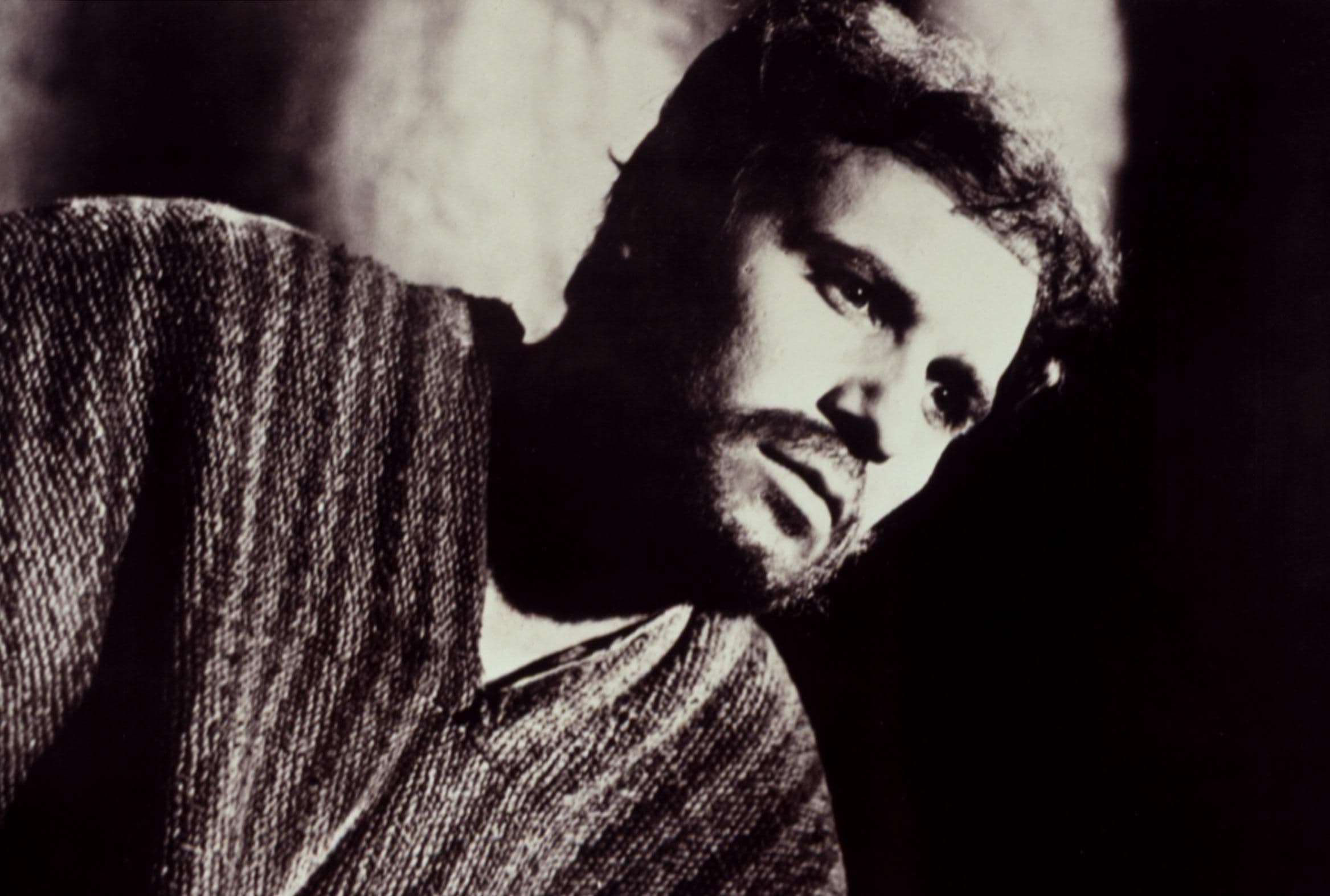

Christ becomes Don Quixote: every effort made seems vain and useless. This is Buñuel's striking insight, the pulsating heart of the film. Father Nazario is no longer merely a Christological figure, but a Cervantine hero, an idealist fighting windmills of evil and incomprehension, condemned to fail not for lack of faith or courage, but due to the inherent absurdity and cruelty of reality. His epic is imbued with a bitter irony: the sacred clashes with the profane and emerges not glorified, but ridiculed, martyred not by executioners, but by human indifference and pettiness. It is a parody of the Passion, where the "calvary" unfolds amidst the dusty landscapes of Mexico and the "disciples" are marginal figures, often willing to betray or abandon their benefactor. Buñuel suggests that, in such a world, even divinity, if it descended among men with intentions of pure mercy, would be condemned to pathetic irrelevance.

Filmed in splendid black and white, the work exhibits a sobriety and cleanliness unusual for the Spanish director, who typically enjoyed surprising and the grotesque. This apparent visual "orthodoxy" is actually one of the film's greatest strengths. Much of the credit goes to the legendary cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa, whose mastery in the use of chiaroscuro, vast skies, and almost pictorial compositions, lends Nazarin a gravitas and depth that enhance the protagonist's moral drama. Far from the surrealist provocations of Un Chien Andalou or L'Âge d'or, Buñuel here adopts a more contemplative visual style, almost documentary-like in its depiction of misery, yet at the same time capable of reaching heights of lyricism and symbolism. The sharp contrast between light and shadow is not merely aesthetic, but reflects the dichotomy between the ideal and the real, between Nazario's purity and the darkness of the world around him. Black and white emphasizes the bareness of emotions and the ruthlessness of the human condition, avoiding chromatic distractions that might have softened the message's impact. It is a stylistic choice that imbues the film with an aura of timelessness and tragic solemnity, in stark contrast to the explosions of surrealism or grotesque excesses that would characterize many of his future works.

Yet even here, Buñuel's directorial talent triumphs in creating a film that violently shakes consciences (as with his other works, but through entirely different means) and captivates with its narrative and cinematography. Nazarin does not need dream sequences or explicit symbols to be radically subversive. Its strength lies in the implacable coherence with which it pushes to extreme consequences the idea that pure goodness cannot survive, let alone triumph, in a world dominated by pettiness, selfishness, and systemic violence. The film won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1959, a sign of its international impact and its ability to disturb even in its apparent narrative "simplicity." As in Simon del Desierto, where a hermit seeks to escape temptations atop a column only to be dragged into the chaos of the modern world, Buñuel here demolishes all illusion of purity and asceticism. Conscience is shaken not by the macabre or the surreal, but by the pure, naked truth of a good man who clashes with reality and emerges defeated, yet perhaps not broken. The final image of Nazario, doubtful and disillusioned, yet still capable of an act of sharing, is the seal of a work that offers no easy answers, but poses burning questions about human nature, faith, and the very possibility of redemption. It is a masterpiece by a filmmaker who, despite changing form and context, never ceased to question the deepest contradictions of existence.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...