1900

1976

Rate this movie

Average: 3.50 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Novecento is a lyrical and rural work, a vast and feverish fresco that attempts the impossible: to encapsulate fifty years of Italian history, with its struggles, horrors, and utopias, in a story lasting over five hours. It is a work-world, excessive, uneven, at times naive, but with such boundless visual power and intellectual ambition that it is an unforgettable experience. A film that could only have been born in the political and cultural cauldron of 1970s Italy, and which today speaks to us with the force of an epic poem.

The story of Novecento is a grandiose metaphor for History itself, with a capital H. Bertolucci adopts the structure and ambition of the great historical novels of the 19th century, from Tolstoy's War and Peace to Hugo's Les Misérables. Like those masters, he uses the events of individuals as a lens through which to observe the impersonal tides that move nations. The similarities with a certain type of European cinema, particularly that of his mentor Luchino Visconti, are obvious but also misleading. While Visconti's The Leopard recounted the end of a world, the aristocratic world, with a twilight sensibility and an almost nostalgic melancholy, Bertolucci stages not a transition but a head-on collision.

His film breathes Marxist dialectic, an explicit and passionate class struggle. It is the work of a son who admires his father Visconti, but who radicalizes his discourse, shifting the emotional and political center of gravity from the master's villa to the peasants' court. Bertolucci's lens manifests itself through a family saga that uses the village as a microcosm to convey a universal message.

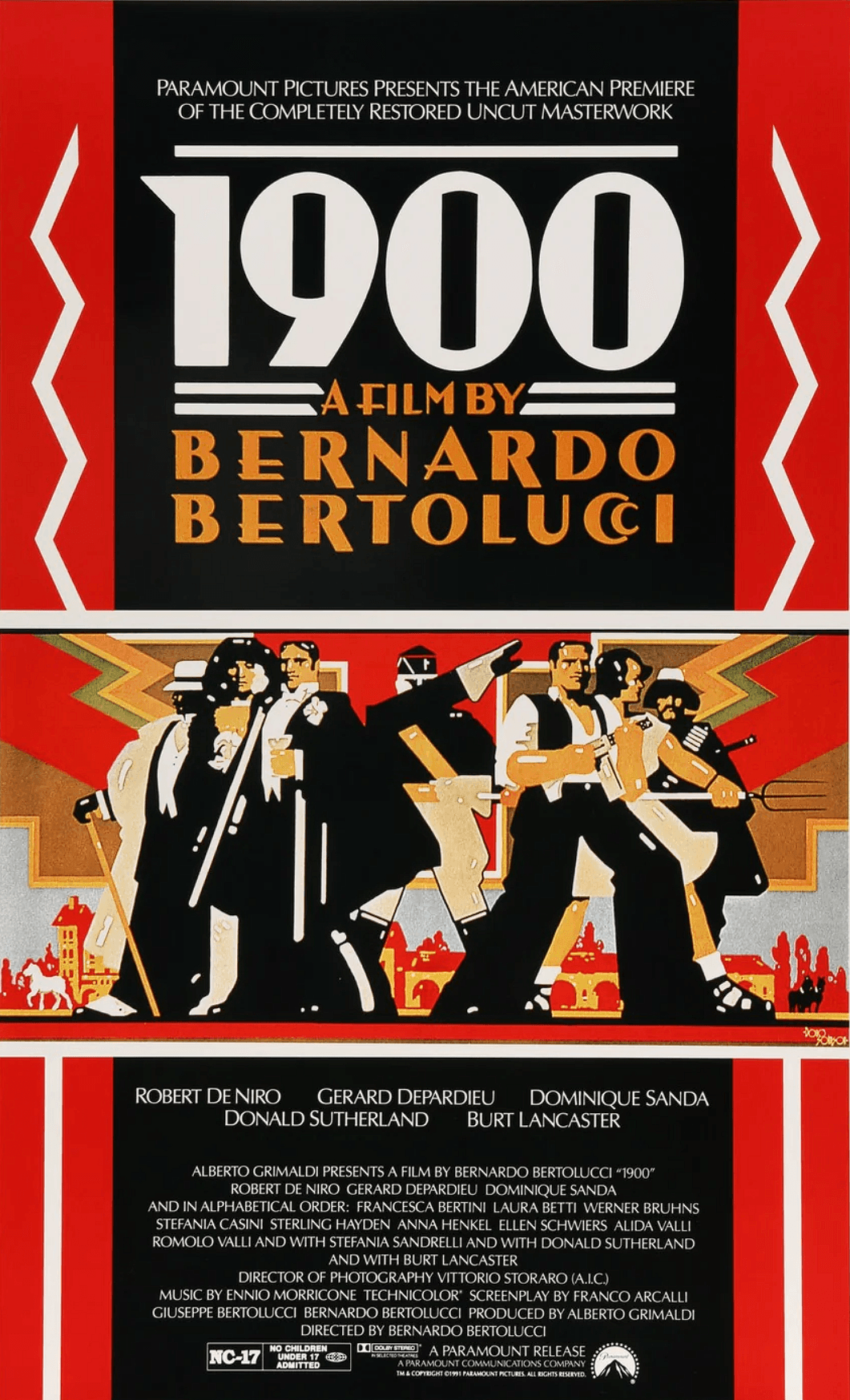

It all begins on a wealthy farm in Emilia on January 27, 1901, the day Giuseppe Verdi died. On the same day, two children are born: Alfredo, son of the Berlinghieri landowners, and Olmo, the illegitimate son of the Dalcò peasants. Their parallel but inexorably intertwined lives will become an allegory of the Italian 20th century. Alfredo (played by Robert De Niro) represents the landowning bourgeoisie, cultured but powerless, passive accomplices of fascism and incapable of action. Olmo (a Gérard Depardieu who embodies the strength of the earth) is the peasant proletariat, proud, socialist, self-aware and fighting for his emancipation. Their friendship, born in childhood and made up of complicity and rivalry, is the complex and contradictory link between the two classes, a bond that history will put to the test until it breaks, only to perhaps recompose it in a new and uncertain form.

But the real protagonist is the landscape. Bertolucci and his wizard of photography, Vittorio Storaro, make the Po Valley not a backdrop, but an active character, an almost mythological entity. Bertolucci's aesthetic is sensual, pictorial, operatic. The camera moves with fluid and majestic sequence shots that embrace the earth and the bodies. Storaro paints with light, assigning colors a precise dramaturgical function: the warm, golden tones of summer and autumn are the colors of peasant life, passion, and socialist utopia. The blinding whites and icy blues of winter are the colors of death, fascist repression, and bourgeois sterility. The choice of a stellar international cast: De Niro, Depardieu, Burt Lancaster, Sterling Hayden, Donald Sutherland, placed in this rural setting and made to act alongside real farmers, creates an alienating and powerful effect, combining the grandeur of Hollywood myth with the almost neorealist truth of the land.

To understand why Novecento is so important is also to understand its troubled production and distribution history. It was a colossal international co-production, a project of almost unthinkable audacity today. The director's original version was over five hours long, and the battles with the producers, especially Paramount for the American market, to reduce the film to a ‘commercial’ length have become legendary. This struggle for the integrity of the work is part of its very nature: a film that, like its peasant protagonists, had to fight against the logic of capital in order to exist in its purest and most radical form. Its release in 1976, in the midst of the Years of Lead, made it a political event. Its portrayal of the Liberation not as a moment of national reconciliation but as a proletarian revolution, complete with a popular trial of the landlord, was a political statement of disruptive force.

In this fresco, the figure of Attila Mellanchini, the fascist farmer played by a chilling Donald Sutherland, becomes the personification of evil. His violence is never grandiose or ideological; it is pathetic, sexually frustrated, and vented on the weakest. The scene in which he first kills a cat and then a child is not gratuitous, but an illuminating and terrible metaphor. This is Bertolucci's thesis on the nature of fascism: a cowardly brutality born of social envy and impotence, which finds its highest expression in the attack on innocent life, beauty, and the future. Attila is not a Nietzschean superman, he is a wretch who, dressed in a black shirt, feels entitled to unleash his basest instincts. It is the banality of evil in its agrarian form. Novecento is a huge work, at times naive in its political faith, but its ambition, visual beauty, and emotional power make it a unique cinematic experience. It is a titanic and perhaps impossible attempt to put an entire century on screen, and in its glorious failure lies its eternal, indisputable greatness.

Main Actors

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...