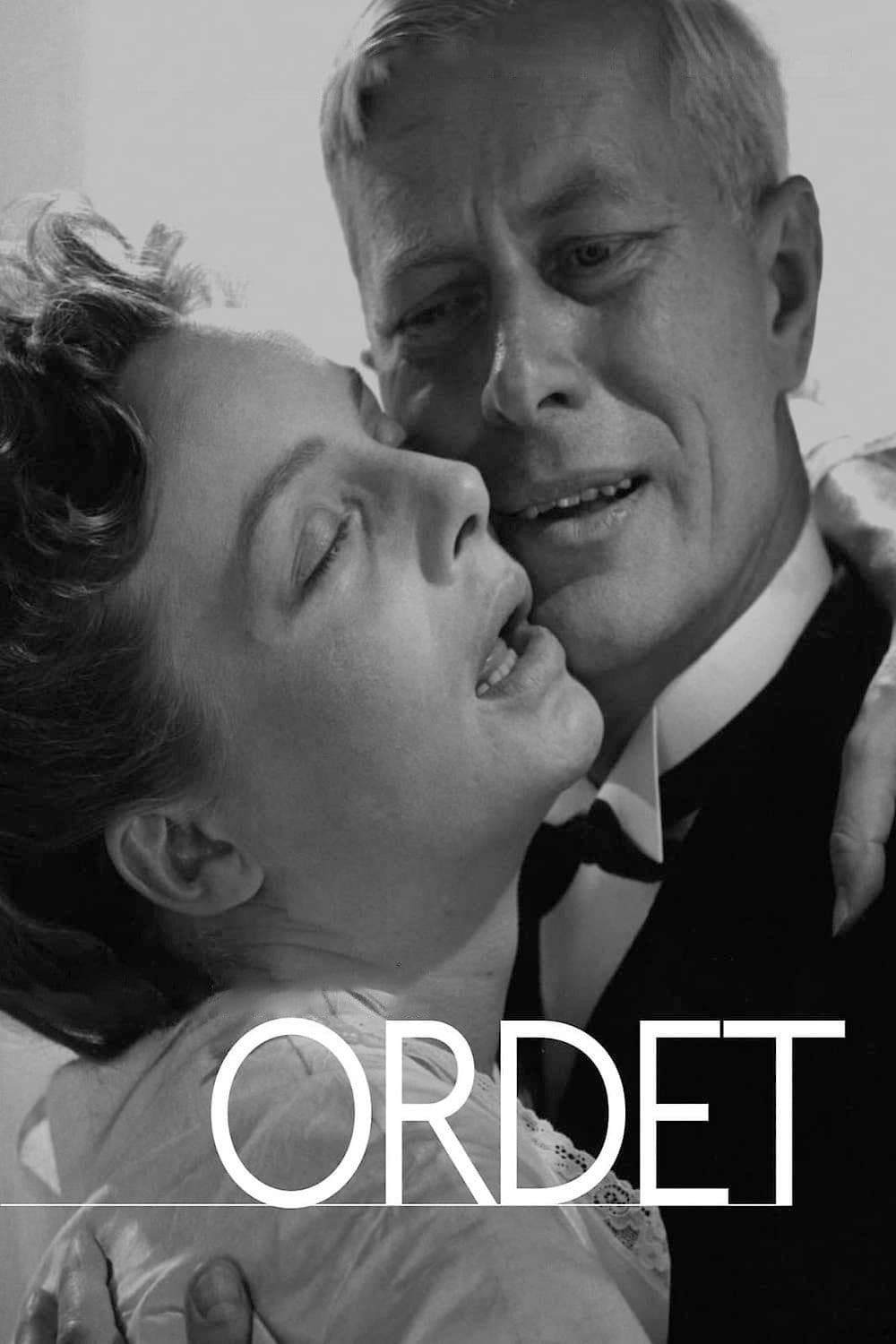

Ordet

1955

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

The penultimate film by the Danish director, Carl Theodor Dreyer, a master whose entire body of work is imbued with an almost obsessive investigation into faith, destiny, and transcendence, stands out for a mystical inspiration infused throughout the work. This is not a didactic or consolatory religiosity, but a tormented, stripped-bare spirituality that delves into the wounds of the human soul with the same merciless lucidity with which he had already dissected martyrdom in The Passion of Joan of Arc or guilt in Day of Wrath.

Undoubtedly a complex film, where the dialogic substratum, made up of sharp theological disputes and deafening silences, comes to collide with the spiritual aura that Dreyer builds with almost geometric precision, giving rise to an atmosphere of substantial suspension of time, place, and action. This suspension is not mere abstraction, but a dramatic artifice that elevates the narrative to a universal parable. Every gesture, every gaze, every breath seems to take on a metaphysical weight, dilating the spectator's perception into a dimension where the sacred and the profane are not distinct entities, but inextricable threads of the same fabric. It is a cinema that breathes and pulsates with a hypnotic rhythm, somehow anticipating the contemplative slowness of Tarkovsky, while maintaining its unmistakable and rigorous austerity.

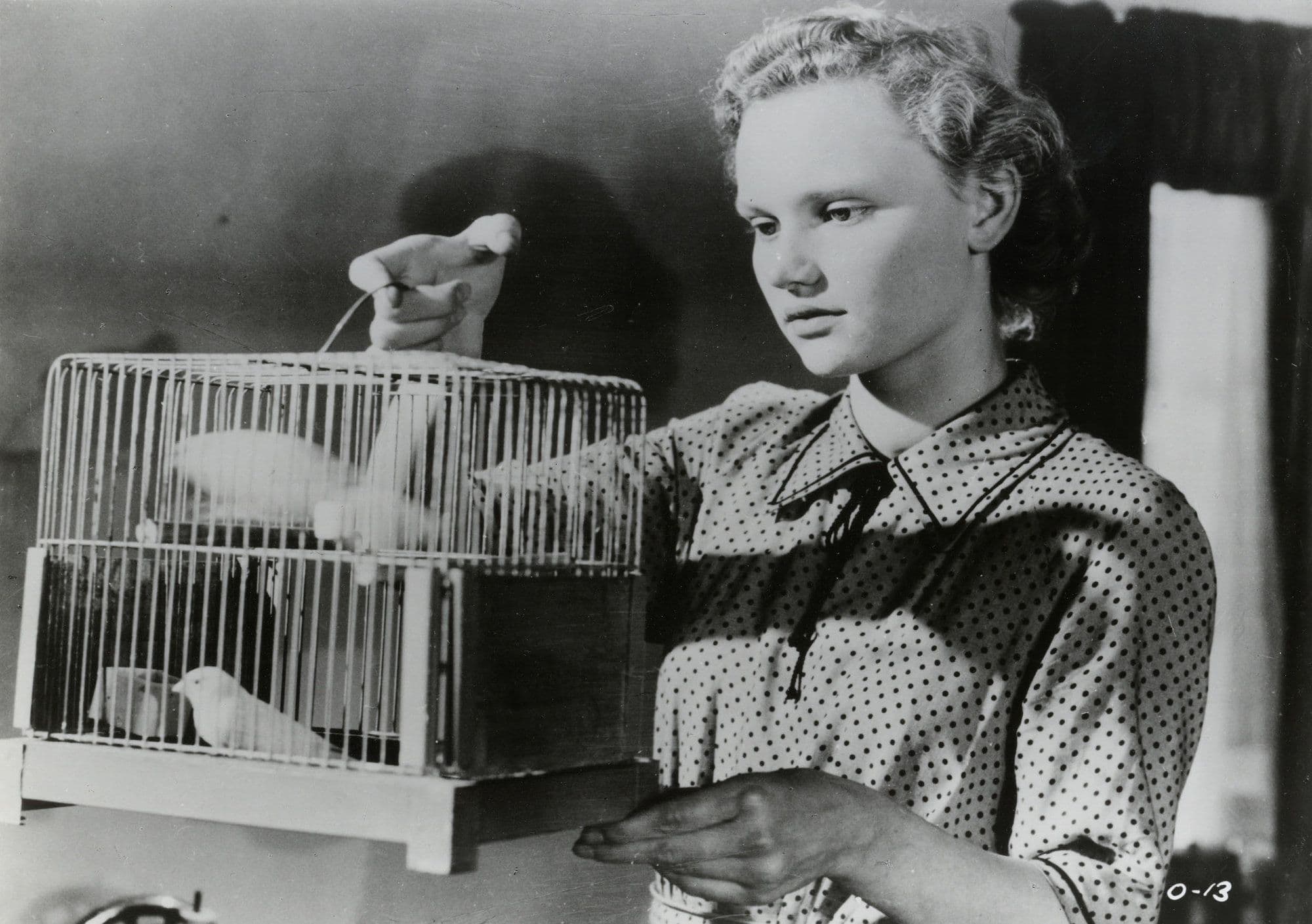

The story is set in 1925 on a Danish farm, an austere and isolated microcosm that becomes the stage for an intimate drama of universal resonance. The patriarch Borgen has three sons: Mikkel, Johannes, and Anders. The central conflict arises from the rigid Lutheranism of old Borgen, a man whose faith is granite-like and unshakeable, anchored to dogma and tradition. The youngest, Anders, falls in love with the daughter of a tailor, Inger, whose father leads a fundamentalist Lutheran sect, the "Inner Mission," even more intransigent and puritanical. Their opposition to the union, based on subtle but insurmountable doctrinal differences, triggers a profound crisis, revealing the tension between dogmatic faith and human love, between divine law and earthly desire. Johannes, the middle son, once a theology student and now considered mad after believing himself to be the reincarnation of John the Baptist, wanders through the farm reciting biblical passages, premonitions, and condemnations; his mystical “madness” is the crowbar that dismantles family and religious certainties.

When Mikkel's wife, Inger, a woman of simple and genuine faith, loved by all for her goodness, dies in childbirth, leaving the family in mourning and despair, the mad mystic Johannes will perform his miracle, restoring things to their predetermined normalcy. And here perhaps lies the work's most fascinating enigma: the nature of this miracle. Is it an act of divine grace, a manifestation of blind faith, or the triumph of human love capable of bending even the laws of nature? Dreyer, with his customary sublime ambiguity, refuses to offer easy answers, leaving the miracle itself as an incarnation of mystery, a bridge cast between the irrational and the possible, and in this lies its greatness, in some ways echoing the complex reflections on the divine and the human by Ingmar Bergman.

A work of immense artistic value, characterized by a dry acting style, which evokes a kind of spiritual minimalism, almost as if the faces were archetypal masks of faith and doubt, an echo of Bresson's search for human "models" but with an even more lacerating emotional vibration; by pressing and aseptic dialogues, true philosophical and theological duels that define the stronghold of faith and dogmatism that is the Borgen home, a crossroads of prayers, invectives, and silences that weigh like boulders; by a dreamlike and almost hypnotic use of the camera, capable of lingering on faces and environments with a contemplative slowness that transcends the narrative to become meditation. Every shot is a pictorial composition, a tableau of light and shadow where the essential emerges from the sobriety of gesture. By wonderful, austere, sumptuous cinematography, by black and white that whips the countryside like a lash, delivering flashes of unheard-of beauty (the same refined photographic research aimed at enveloping the rural environment in black and white that we find in Haneke's The White Ribbon). But while Haneke employs his glacial whiteness to reveal the hypocrisy and latent violence in a Puritan society, Dreyer uses it to exalt the purity of spiritual inquiry, to make the invisible tangible, to capture divine light even in the deepest shadow of human suffering. It is a Caravaggio painting transposed onto film, where beams of light cleave the darkness to reveal inner dramas and unexpected epiphanies, making Ordet not just a film, but a transcendent and unforgettable experience.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...