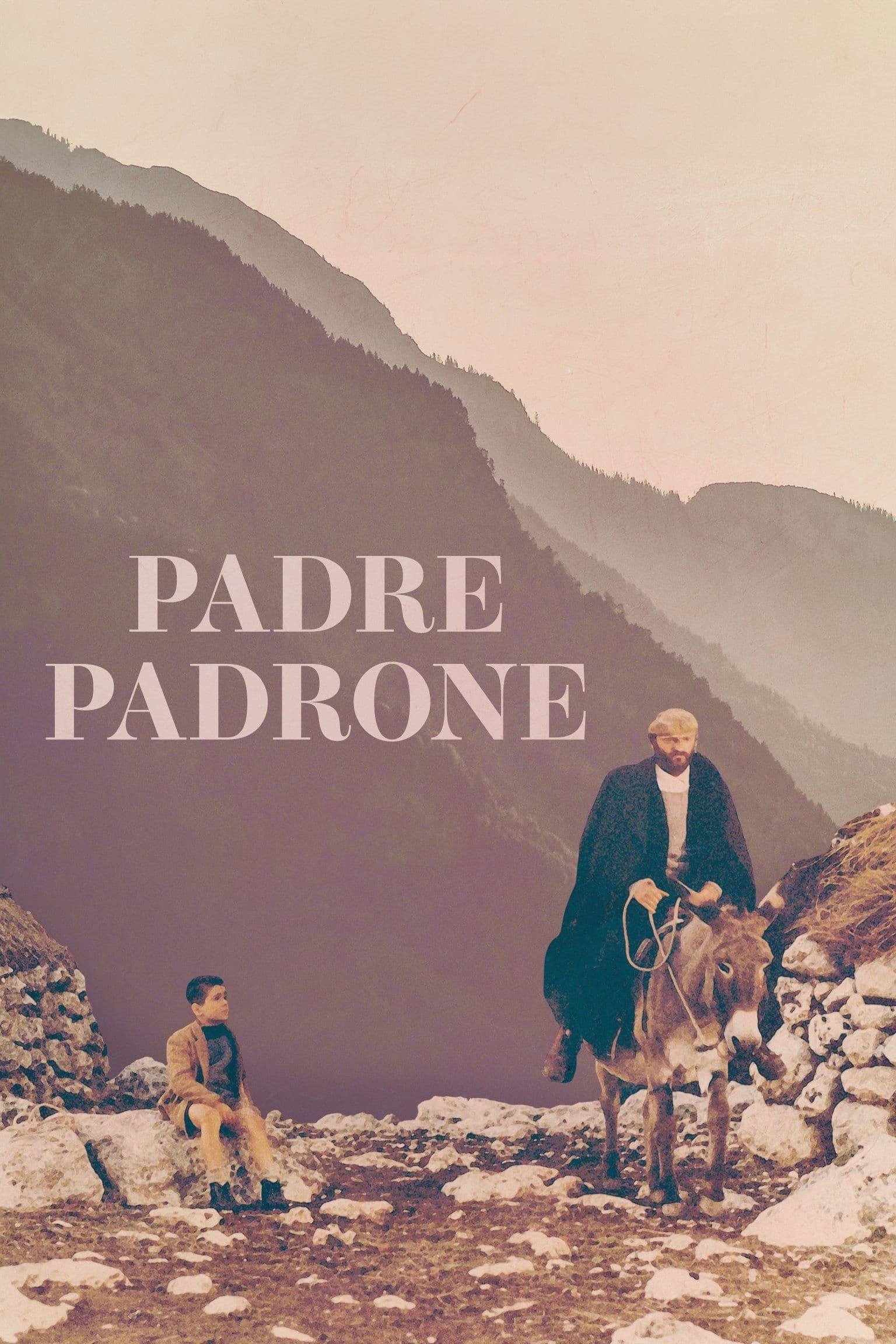

Padre Padrone

1977

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes and drawn from a splendid autobiographical book by Gavino Ledda, this film by the Taviani brothers is primarily a poetic attempt to shed light on the man-nature relationship, not as a bucolic idyll, but as an ancestral bond of survival and, perversely, of imprisonment. Secondly, it delves into inter-family relationships in rural areas where cultural backwardness went hand in hand with economic backwardness, in order to highlight their primordial harshness but also the indissoluble bond that, like iron pincers, grips the individual to their origin, preventing their full emancipation. The cinema of the Tavianis, here at its expressive peak, once again confirms itself as a crossroads of neorealism and mythical inspiration, capable of transfiguring chronicle into epic, personal drama into universal allegory.

The story is indeed centered on Gavino, a young man torn from society by his father – an act of symbolic violence that resonates like an ancient sacrifice – to herd a flock of sheep on the harsh and silent mountains of Sardinia. An existence that is an atavistic condemnation, a legacy of toil and ignorance perpetuated from father to son. The boy will find himself immersed in an alienating solitude, a forced mutism that relegates him to an almost animalistic dimension, in a harsh and strong nature, in the complete silence of the woods. A silence that, paradoxically, becomes his first teacher, a primordial language made of earth sounds, of pastoral rhythms, a vocabulary of instincts and vital necessities, light years away from what the "civilized" world could offer him.

Hovering over him is the odious authority of his father, an embodiment of patriarchal tyranny, a monolithic and almost archetypal figure of a world stubbornly resisting progress. A father who forces him into that meager life, an invisible but iron chain that binds Gavino to his misery. His figure, however, is not a simple stereotype of the despotic parent; he is also a victim of a system, a prisoner of a mentality that views education as a useless luxury, if not a threat, and the subjugation of children as a sacred duty, a distorted and self-destructive code of honor.

The departure for military service in Italy, a catalyst for an unprecedented rebellion, marks the first true break with that archaic world. The experience of the barracks, the discovery of another language, the encounter with a more complex society, and attending evening school, which opens the doors to knowledge and the written word, are crucial stages of an arduous and painful liberation. Economic independence from his father, a consequence of this intellectual illumination, will lead him to try and break away from the strict parent, not only physically but also and above all culturally and psychologically. It is a path of rebirth, a Bildungsroman sui generis, unfolding between pastoral isolation and the yearning for knowledge. Gavino not only learns to read and write but becomes a philologist, a linguist, a man who has found in the word his true instrument of power, the "master" of his own existence.

The work truly excels not so much in the complicated relationship between father and son – albeit imbued with an almost Shakespearean tension – as in the deep and often ambivalent communion with a hostile yet simultaneously protective nature. It is in the solitude of the pastures that Gavino learns to communicate, first with animals, then with himself, developing an inner language that will be the seed of his subsequent emancipation. Sardinian nature, captured with cinematography that is itself poetry – harsh, luminous, almost tactile – becomes a character in its own right, a mirror of tormented human dynamics and the cradle of primordial wisdom. Consider the snake sequence or the moment Gavino learns to play the accordion, a symbol of freedom and artistic expression that contrasts with the imposed mutism.

Memorable is the scene where the father goes to pick Gavino up from school to remove him from society forever and place him in charge of his flock of sheep. The scene is of exaggerated harshness, almost biblical in its merciless representation of generational and cultural conflict: the man explains his reasons to the teacher with a blind pride, almost grandiose in his tragic ignorance, convinced he is acting for his son's good and out of respect for a millennia-old tradition. Meanwhile, Gavino, standing amidst the desks, helpless before a fate already written, cannot hold his urine out of fear, in an act of infantile humiliation that reveals his absolute vulnerability and the implicit violence of that "handover". This scene, laden with symbolism, condenses the drama of a generation struggling to break free from the chains of an anachronistic past, a silent cry of rebellion destined to explode only years later.

An extraordinary work, for the cinematography by Mario Masini and Giuseppe Ruzzolini, which captures with its rigorous and moving aesthetic the bare essence of a landscape and humanity, and for the emotional impact it leaves an indelible scar on the viewer. It is a film that speaks of liberation, not only individual but collective, from the tyranny of ignorance and blind tradition. A hymn to knowledge as the supreme form of freedom and as the only way to finally become the "master" of oneself. A masterpiece that continues to question, with its brute force and profound tenderness, the meaning of roots, identity, and autonomy.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...