Parasite

2019

Rate this movie

Average: 4.50 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Do not be fooled by the film's title.

At first glance, the term Parasite might evoke the horror genre, or other subgenres that Bong Joon-ho has, moreover, not hesitated to explore in his previous works.

Since Memories of Murder (2003), which introduced him to Western audiences, the South Korean director has continually navigated the tempestuous waters of various cinematic genres, from science fiction (Snowpiercer) to intimate drama (Mother), passing through Horror (The Host) or poetic Fable (Okja), which definitively makes him an unclassifiable artist.

What is striking about Bong Joon-ho is his perfection in mastering both form and content.

The film was crowned at the 72nd Cannes Film Festival with a well-deserved Palme d'Or, consecrating the talent of a director and effectively transforming him into an authentic star, whereas previously he was known and appreciated by only a handful of viewers.

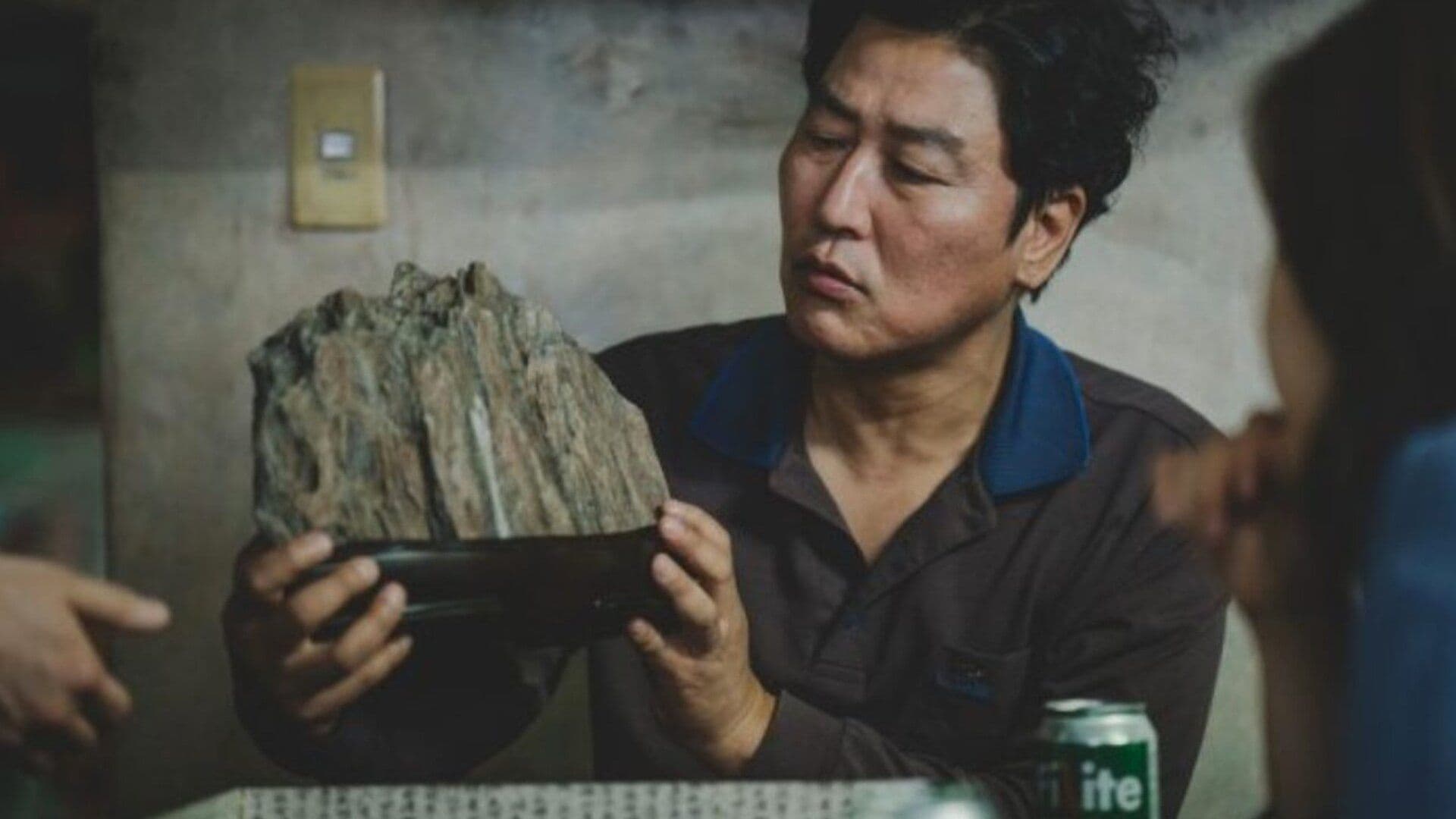

The film's parasite is therefore neither a monstrous creature nor a mutant virus, but rather the story of a family living in modern-day Seoul who, deprived of work, are driven to enter into a relationship of dependence with a wealthy family.

“An ironic title,” says the director, who paints a very grim vision of his country.

That of two irreconcilable Koreas, whose geographical division is mirrored by an analogous division between social classes.

Two worlds, rich and poor, and a boundary as insurmountable as the 38th parallel that divides the two Koreas.

The metaphor of division is embodied in the film by what is found in the basement and on the habitable surface of a large and magnificent mansion, built in the affluent districts of Seoul.

Here resides the Park family, who purchased the prestigious mansion from the Architect who built and lived in it.

The family is a kind of caricature of the new Korean elite who made their fortune with new technologies, imitating the Western lifestyle and peppering their language with Anglo-Saxon phrases (in this, recalling the 19th-century passion of the Russian Nobility for the French language).

Its neatly mown lawn, its immense panoramic window allowing the sun’s caress to enter, its pantry full of food make Kim and his family dream, a core unit huddled in a stinking basement surrounded by vagrants and drunkards, without any hope of redemption, and in dire financial straits.

When Kim's son, Ki-woo, is hired by the Parks, by means of a forged diploma, to give English lessons to their daughter, Mr. Kim will devise a diabolical plan to supplant the current household staff and transfer his wretched family into the Parks' service.

His sister, father, and mother are thus hired one after another to carry out the various tasks needed in the House (art teacher, driver, housekeeper), without the Parks suspecting they are dealing with members of a single family.

To get hired, the Kims use methods that are nothing short of perverse, such as trapping the chauffeur in a fake sex scandal or eliminating the housekeeper by exploiting her peach allergy.

However, an unexpected event will disrupt this elaborate deception, and the trap will close on the Kims, bringing them back to their starting point: the bowels of Seoul at the moment when torrential rains overflow from all the city's sewers, highlighting the misery on the surface.

In a dramatic crescendo, of which Korean cinema has held the trademark for years (see, for example, the Mephistophelian cinema of Park Chan-wook or the metropolitan cinema of Sang-ho Yeon), what began as a subtly corrosive social comedy, contrasting the warmth and exuberance of the Kim family with the cold and fictitious universe of the Parks, suddenly transforms into a Shakespearean drama.

Neither family is truly to blame for the relentless mechanics about to unfold; everything appears governed by the cause-and-effect relationship that regulates social interactions and class divisions.

“It’s a comedy without clowns, a tragedy without villains,” the director states in a Fellini-esque manner.

Obscured tones that gradually instill anxiety and unease through the simple play of mise-en-scène, utilizing slow shots and panoramic sweeps that explore every corner of the house and the people who inhabit it.

Bong Joon-ho is here at the peak of his art in this subterranean class struggle.

And he conveys a message of unfathomable pessimism about the state of our world, where the family remains the last refuge, but also, in some ways, the inescapable trap.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...