Playtime

1967

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A cathedral of glass, steel, and millimeter-precise gags built by a master of comedy, a visionary who almost sacrificed himself and his career on the altar of an almost insane artistic ambition. All this is Playtime, the latest gem from the great master of surreal comedy Jacques Tati, who, tired of being identified with his alter ego, the ineffable and clumsy Monsieur Hulot, decided not to kill him off, but to do something much more radical: lose him in the crowd, reduce him to a silhouette among many, so that he could direct his true magnum opus. The result is a gigantic comedy, a visual and auditory symphony about the modern city that is both a scathing critique and an affectionate love letter. It is one of the most daring, formally revolutionary, and simply entertaining films ever made, a work whose complexity is revealed with each viewing.

The film apparently follows two almost non-existent narrative threads: a group of American tourists arriving in Paris for a 24-hour tour, and Monsieur Hulot, who has to go to a job interview in a labyrinthine office building. But this is just an excuse. The real protagonist of the film is the city itself, or rather, “Tativille”: a hypermodernist and fictional version of Paris, entirely built by Tati on a vast piece of land on the outskirts of the capital. This production choice, a titanic undertaking that led the director to bankruptcy, is the key to understanding the film. Tati did not want to comment on reality, he wanted to construct his own, a hermetic world of reflective surfaces, right angles, and impersonal materials, in order to study its absurdities like an entomologist studies a colony of insects. In this world, Hulot is no longer the center of comedy. He is a lost compass, an occasional disruptive element. The real comedy is widespread, democratic, scattered in every corner of the frame. You never know for sure where you're going to laugh, and this makes subsequent viewings as satisfying as the first, if not more so.

To appreciate Tati's radicalism, a parallel with his only peers in the pantheon of physical comedy, Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, is illuminating. They are three masters representing three different worldviews. Chaplin is the sentimentalist, his Charlot is an icon of pathos, a tramp whose struggle for dignity and love in a cruel world is the driving force of the comedy. His is a cinema of the heart, focused on the emotions of the individual. Keaton is the stoic surrealist, his stone face a fixed point in a chaotic and often malevolent universe, a cosmos of rebellious objects and adverse natural forces. His comedy arises from the clash between the unperturbed logic of the individual and the absurd logic of the world.Finally, Tati is the observant architect. His Hulot is neither a tragic hero nor a cosmic acrobat. He is a kind, old-fashioned man, an unwitting catalyst of chaos whose analog humanity conflicts with a digital world. But Tati's genius lies in not focusing solely on him. He uses deep focus photography and fixed, wide shots, often shot in the glorious 70mm format, where every plane of the image is in focus. The viewer's eye is free to wander, to discover the little gag unfolding in the background while another happens in the foreground. It is cinema that demands an active viewer, inviting them to play. His compositions are reminiscent of the crowded paintings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, where dozens of small stories unfold simultaneously.

But what makes Jacques Tati so great in the history of cinema? His greatness lies in this unique fusion of popular comedy and formal avant-garde. He understood, before many others, that in modernity, sound was as important as image. The sound design of Playtime is a masterpiece. Dialogue is reduced to a multilingual murmur, an almost incomprehensible background buzz. The real stars of the sound are the noises of the modern world: the synthetic hum of skai armchairs, the pneumatic hiss of doors, the sharp click of a lighter, the clicking of heels on a shiny floor. It is a concrete symphony of the artificial, which Tati uses to create auditory gags as complex as the visual ones.

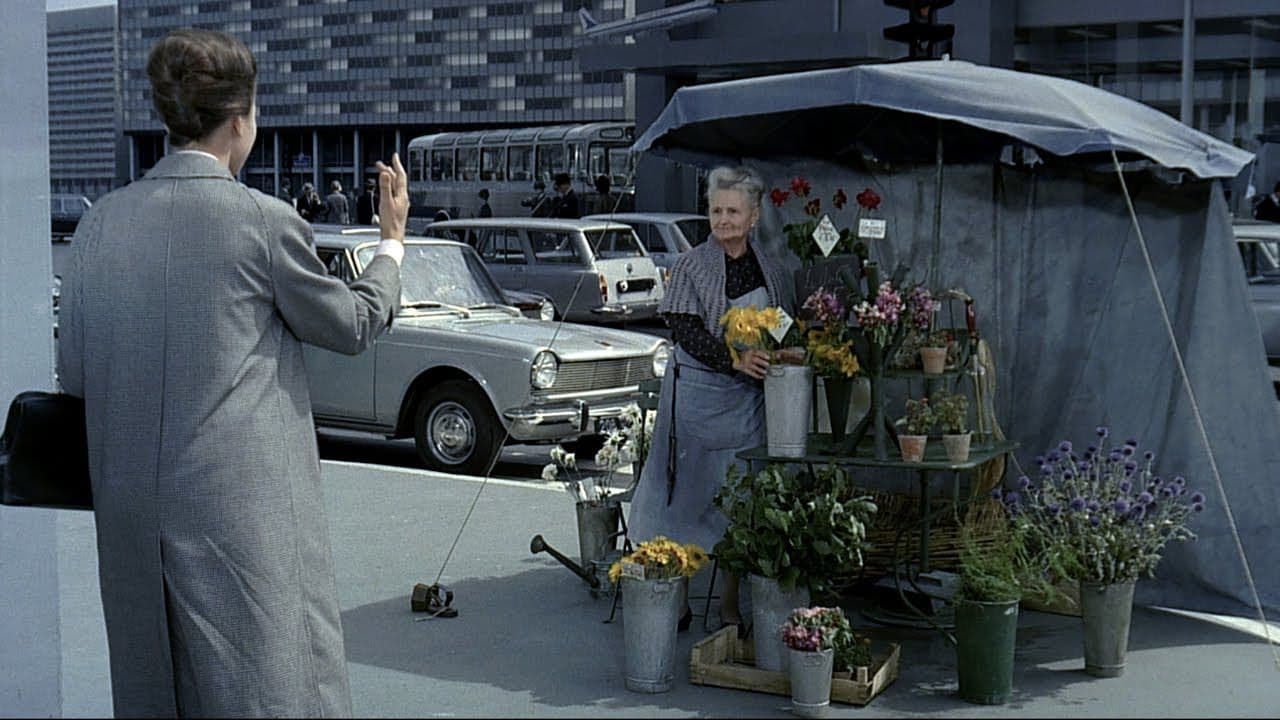

And then there is his worldview. Tati criticizes the sterility of modernist architecture, its claim to efficiency that translates into alienation. But he is never a cynical or despairing critic. His gaze is always imbued with an affectionate humanity. The central sequence, and perhaps the most beautiful, is the opening of the Royal Garden restaurant. What begins as a disaster (workers finishing installations as customers enter, pillars crumbling, systems malfunctioning) slowly transforms, thanks to Hulot's unwitting intervention and the resilience of those present, into a veritable celebration. The ruins of modern design become the stage for authentic, chaotic, and joyful human interaction. Tati tells us that life, with its wonderful imperfection, always triumphs over the sterile perfection of plans. The film's ending, with the carousel of cars in a roundabout turning into an almost joyful ballet, is the synthesis of his thinking: even in the heart of modern alienation, moments of grace, playfulness, and playtime can be found. This work is Tati's magnum opus, a work whose boundless ambition doomed it to commercial failure but ensured its artistic immortality. It is a film to be seen and seen again, an experience that offers new discoveries with each viewing, confirming that genius sometimes consists simply in looking at the world with infinite attention and affection.

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...