Rear Window

1954

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

"Rear Window" is perhaps the perfect film, a narrative mechanism of dazzling purity and beauty. This perfection stems not only from its impeccable screenplay, but from its bold and meticulous mise-en-scène. The decision to confine almost all the action to a single, vast set – Jeff's courtyard and apartment – transforms a potential limitation into its greatest strength. The environment reveals itself as a panoramic stage where a multitude of human dramas unfold, and each window becomes a meticulously framed mini-film, capturing our gaze with the same relentless fascination that grips the protagonist.

The story is that of a photographer confined to a forced domestic convalescence due to a broken leg. And Jefferies, portrayed by a masterful James Stewart in his expression of frustration and keen observation, is our guide in this microcosm. Ironically, a man whose profession is to capture reality through the lens of a camera suddenly finds himself reduced to a passive observer, dependent on his telephoto lens to explore a world that, paradoxically, has shrunk to his window.

He begins almost as a game, spying on his neighbors from his window overlooking the building's courtyard. What starts as an innocent pastime to combat boredom – a kind of live human theater, made of fragments of other people's lives – gradually evolves into a disturbing criminal investigation, a moral and existential puzzle. The banal and repetitive daily lives of the neighboring tenants shatter to reveal a macabre reality, a heart of darkness hidden beneath a surface of bourgeois normality. Slowly, he becomes aware that one of the quiet neighbors he is spying on is actually hiding a murderer.

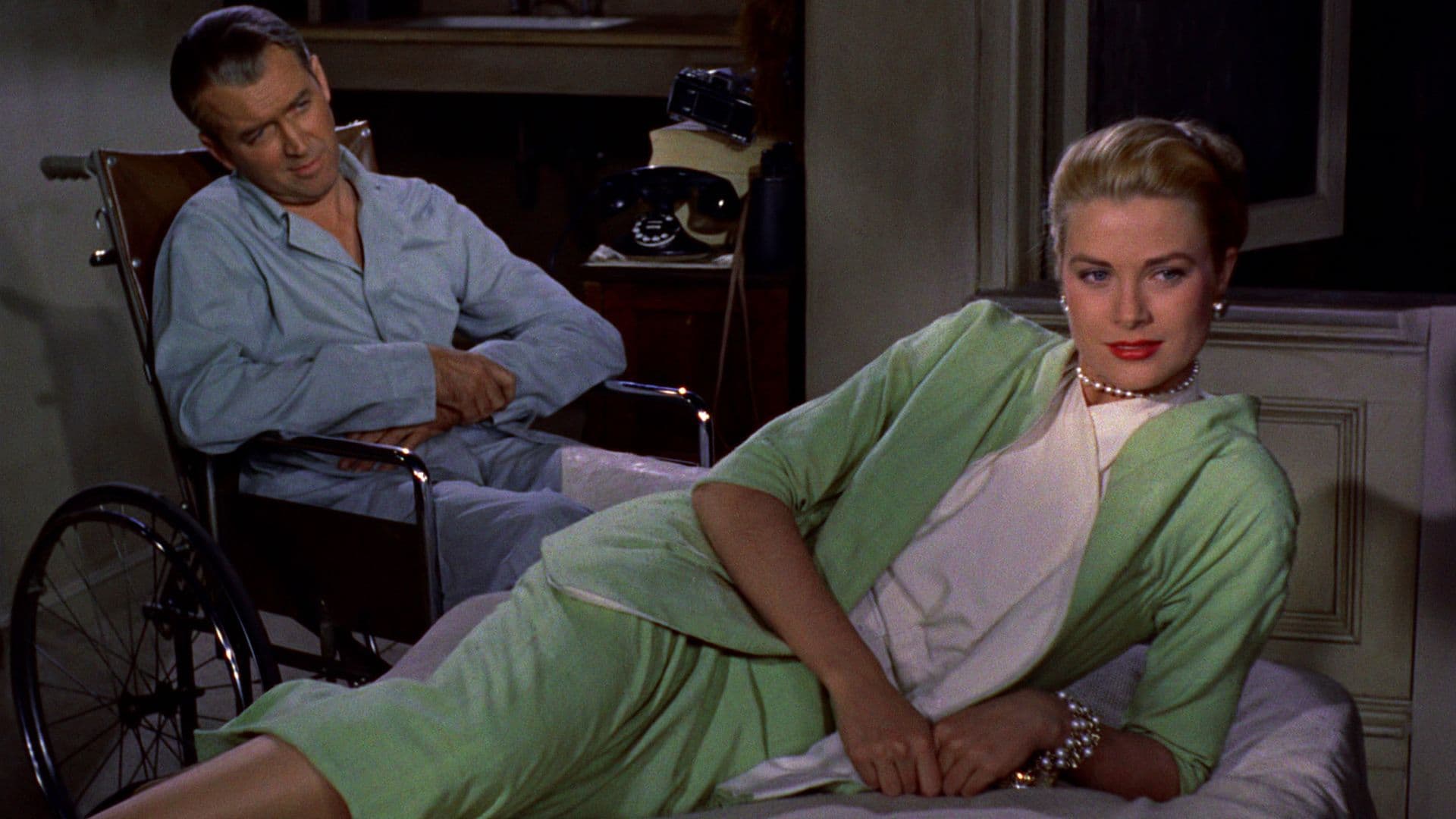

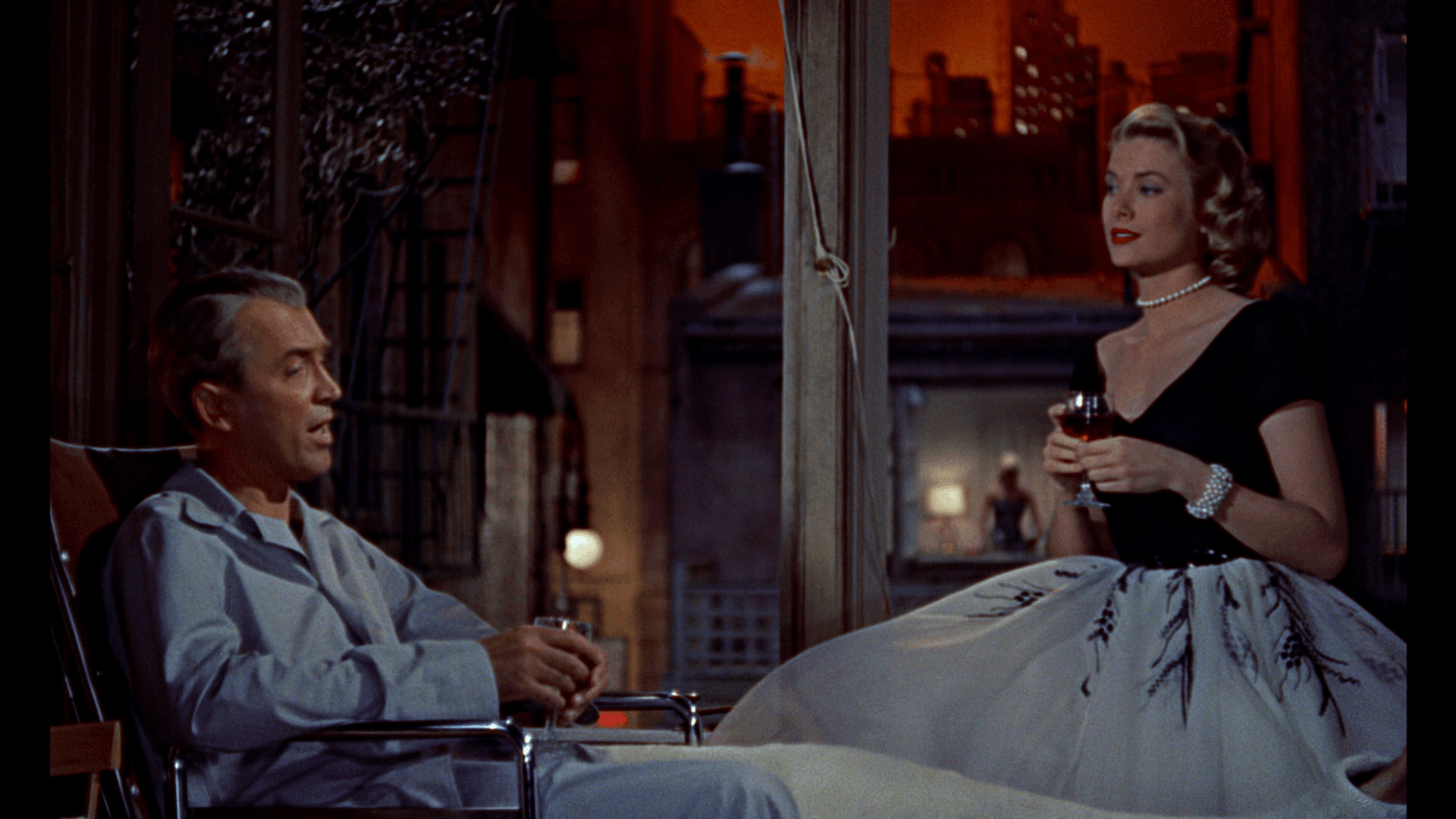

Assisting him in his domestic investigation is his fiancée, an ethereal Grace Kelly, never so beautiful. And indeed, Grace Kelly as Lisa Fremont is much more than an angelic figure: she is the embodiment of modernity, a high-society woman, sophisticated and intelligent, whose initial reluctance towards her fiancé's obsessions transforms into audacious participation. Their relationship, with its tensions between Jeff's desire for an adventurous life and Lisa's propensity for marital stability, adds a further layer of emotional complexity, reflecting the social anxieties of 1950s America.

A subtle and almost morbid journey into voyeurism, into the sordid mind of a killer observed from the shadows. And it is here that the film reaches heights of meta-cinematographic genius. Hitchcock doesn't just show us Jeff's voyeurism; he makes us complicit. It is we, sitting in the darkness of the cinema, who spy through his gaze, sharing his curiosity, his excitement, and, finally, his fear. The very act of cinematic viewing is dissected and questioned, transforming the viewer from a mere passive observer into an active participant in a moral experiment on the ethical implications of the gaze.

Hitchcock turns the scrutiny of his work back on himself (we know the director faced trouble for alleged voyeurism incidents), and in this sense, Jeff undoubtedly has a veiled autobiographical connotation. The director, known for his obsessive attention to detail and his predilection for control, imbues Jeff with a good deal of his own personality and impulses. Rumors, never fully confirmed but persistent, regarding some of his private "investigations" into actresses or crew members, find in Jeff a self-reflective projection, almost a self-critique. It's as if Hitchcock admitted, through his on-screen alter ego, the thin line separating artistic observation from pathological intrusion, inspiration from fixation.

Hitchcock's hero is forced into a physical confinement due to his temporary infirmity. This physical constraint, far from limiting the narrative scope, enhances it. As in other Hitchcockian works (consider the confined set of Rope or the ship at the mercy of the sea in Lifeboat), spatial limitation becomes a catalyst for psychological and dramatic tension. Starting from this constraint, the film immerses the viewer in the man's frustration, boredom, and need for escape through this device, which initially serves as a game but then, characteristic of all Hitchcock films, undergoes a transformation, simultaneously escalating the narrative tension. The progression is masterful: from the innocuous amusement of spying on an exuberant ballerina or a newlywed couple, it moves to the discovery of a potential crime. The claustrophobia of Jeff's apartment projects onto the courtyard, which transforms from a stage of ordinary lives into a theater of latent horrors, a Panopticon where identities are constantly under scrutiny, or so we believe. The tension is not just in "what will happen," but in "how Jeff will manage to prove it" and, above all, in "who will believe him?"

This extremely high level of suspense perfectly integrates into the narrative mechanism, so much so that the film has now become an archetypal benchmark for every thriller. Its influence is palpable in countless subsequent works, from Brian De Palma's Body Double, which explicitly reuses its premises, to contemporary thrillers that play with limited perspective or the theme of observation.

Hitchcock explained the difference between Surprise and Suspense. A bomb under a table explodes; this fact is a surprise. In another case, we know the bomb is under the table, but not when or if it will explode, and this is Suspense. Rear Window is the perfect embodiment of this lesson. The "bomb" is not a mechanical device, but the horror lurking in banality, the slow and inexorable escalation of a suspicion that transforms into terrifying certainty. Suspense does not arise from a sudden event, but from our awareness (or semi-awareness) and Jeff's, that something terrible is happening or has already happened, and from our powerlessness to stop or verify it. Every small clue, every variation in lighting, every distant sound, every glance between Jeff and Lisa, contributes to weaving this dense web of anguish, a growing anxiety that inextricably links us to the protagonist's fate. It is a masterpiece of visual and psychological orchestration, an exercise in style that defines the genre and continues to captivate with its timeliness and depth. And if he says so, you can believe him implicitly.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...