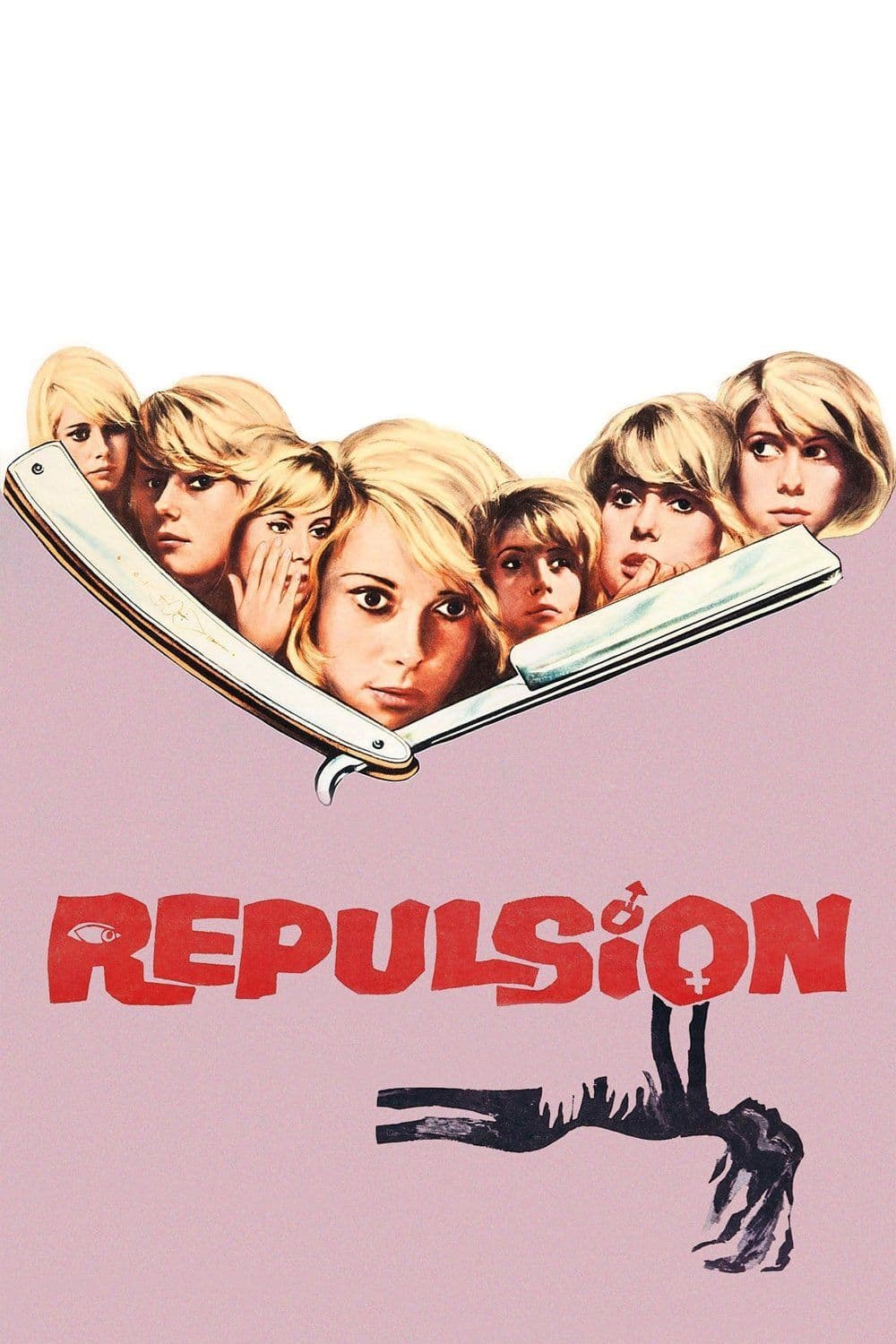

Repulsion

1965

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Polanski, fresh from Poland where he had already demonstrated his mastery with works like Knife in the Water, ventures into British cinema with Repulsion, the first chapter of what would later be defined as his "apartment trilogy." In this first stage of his voluntary exile, the auteur throws himself with ruthless lucidity into claustrophobic atmospheres where mental unease and distorted reality grip the narrative in a breathless vise. The film, in fact, is not just a genre exercise, but an almost documentary-like immersion into a sick psyche, foreshadowing the obsessive explorations of paranoia and reclusion that would also characterize the subsequent Rosemary's Baby and The Tenant.

Catherine Deneuve delivers a great, truly great artistic performance, an actress already an icon of grace and sophistication, here called upon to face a difficult and creeping role, disarming in her initial vulnerability and chilling in her subsequent metamorphosis. Her Carol is an embodiment of the most intimate terror, succeeding so well in the endeavor as to become an inescapable icon of the work itself, a face sculpted into the psyche of cinema that anticipates the complex female explorations of works like Buñuel's Belle de Jour, albeit with diametrically opposite outcomes in voyeurism and liberation. Deneuve's almost ethereal delicacy brutally contrasts with the spiral of horror and degradation that envelops her, making her fall even more agonizing and credible.

The story is the biography of a young Belgian woman, Carol Ledoux, transplanted to London. The woman works in a beauty salon, a superficial and polished environment, and apparently leads a life of agonizing normality, marked by daily routine and cohabitation with her sister Helen. But behind the screen of form, behind the façade of bourgeois composure, lies a deep and unstable psychic unease, a terror diffused over everything that surrounds her, which becomes a hostile symptom of a reality intent on seizing her. It is not an external horror, but a progressive dissolution of the self, an inexorable wave of madness that generates from the depths of her troubled mind and contaminates the surrounding world.

This terror is not generic, but manifests through a perceptual distortion masterfully orchestrated by the director. Sounds become deafening: persistent drips, the obsessive ringing of bells, indistinct murmurs filtering through the walls, everything contributes to hammering Carol's already fragile psyche, transforming the apartment into a sounding board for her phobias. And the images, oh, the images! Polanski violently drags us into her hallucinated subjectivity: cracks opening on the walls, like festering wounds of the soul, hairy hands sprouting from the walls to grab her, objects deforming and people becoming amorphous threats. Black and white, far from being a limitation, elevates the vision to an archetypal nightmare, devoid of the distractions of color, focusing attention on the psychological plot and the progressive disintegration of reality. It is a use of cinematography that recalls expressionistic bleakness, while placing it in a hyperrealistic context that makes the disturbance even more unsettling.

Thus, the phases of a life in which suffering and disillusionment, silent and unexpressed, give way to a creeping madness are retraced. The core of this unease, skillfully hinted at and never didactically explicit, lies in a deep and unresolved repulsion for male sexuality, perhaps rooted in a childhood trauma that the ending, with a chilling photographic shot, seems to suggest. Hers is a reclusion psychosis, a self-imposition of a mental prison that, paradoxically, materializes within the apartment walls, transforming it from a refuge into a deadly trap. The departure of her sister Helen, Carol's only anchor to reality, serves as the definitive catalyst, opening the doors to paranoid isolation that will culminate in violence.

Famous is the scene in which the woman's sister leaves home, leaving the young woman locked in with a dead rabbit in a slow state of decomposition. This image is not a mere shock for its own sake, but a powerful symbol of Carol's inner putrefaction, a visceral premonition of her slow but inexorable descent into the abyss. The rabbit, an innocent and defenseless creature, reflects her own vulnerability, while its organic decay is the visual analogue of the dissolution of her sanity and her personal and moral hygiene. It is a detail that creeps, like the terror Carol experiences, under the skin, transforming the ordinary into the grotesque, the everyday into a premonition. This element, combined with rotting food and the disorder invading the apartment, creates a symphony of decay reflected in the protagonist's psyche.

Repulsion is a film like an incandescent blade that tears flesh with cyclical, mechanical, ferocious slowness. It is a cinematic experience that not only frightens but profoundly disturbs, forcing the viewer to confront the fragility of perception and the instability of reason. Polanski shows us that the most authentic horror does not reside in monstrous creatures or supernatural entities, but in the deep abyss of the human mind, in the disintegration of the self when reality proves too burdensome, too threatening, too tangible. A masterpiece of psychological horror that, nearly sixty years after its release, retains its chilling power and inescapable relevance.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...