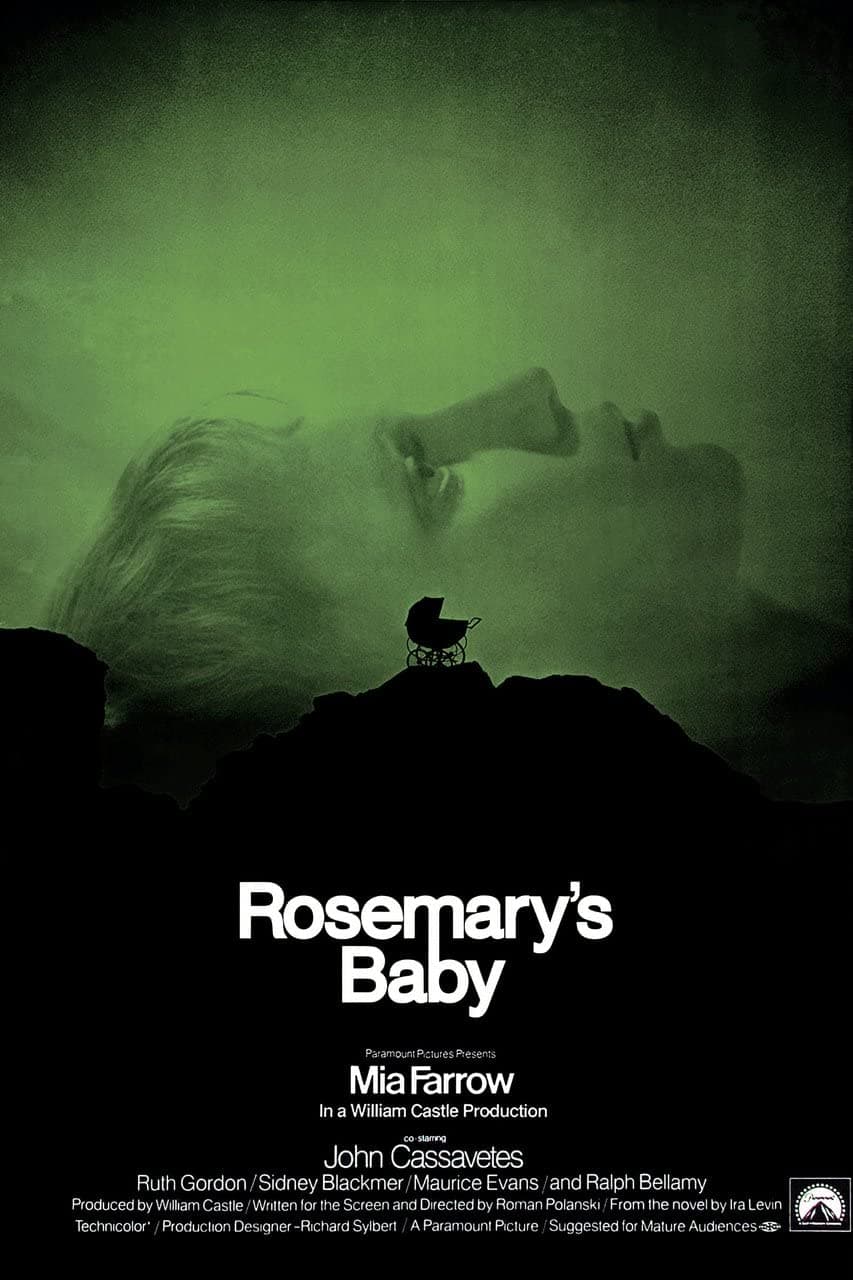

Rosemary's Baby

1968

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Roman Polanski arrived in Hollywood in 1968, with a considerable amount of experience (three films in Poland and one in the UK) and, above all, with the firm intention of making the most of the opportunity that lay before him. Paramount had summoned him for a project, and the Polish director felt like someone chosen by fate. He was a resolute, sharp, and tremendously perspicacious man, yet at the same time he maintained a fatalistic view of life, in which man found his destiny through entropic determinism. Roman already had a shortlist of potential texts for his first American film. But the book he chose struck him like a bolt of lightning, compelling him to rush into filming. The book in question was Ira Levin's Rosemary’s Baby, a Gothic-metropolitan novel in which Satanism and esotericism crept in among the comfortable walls of New York skyscrapers, shaking the metropolitan certainties of their occupants. Polanski immediately recognized the immediate narrative power in that somewhat clichéd story, just as Kubrick sensed the intellectual depth of Stephen King's The Shining.

For the lead roles, two young actors almost unknown to the big screen were cast: Mia Farrow was primarily known for her participation in the TV series Peyton Place but had never worked in cinema, while John Cassavetes also had extensive television experience but was almost never seen on the big screen. It is said, and it seems to be confirmed, that for the male lead, the producers had already decided on Jack Nicholson, a rising star at the time. But when Polanski saw him, he said that Nicholson's magnetic charm gave the character of Guy too sinister an aura: something that, at least in the film's early scenes, should not happen. Thus, Nicholson was rejected. For the location, an old and unsettling building just a few steps from Central Park was chosen: the Dakota Building. Polanski wanted it for the sense of unease and decadence that permeated every single brick. It is curious to note that John Lennon would come to live in that building in 1980 and would brutally meet his death there two years later.

The story centers on the young couple Guy and Rosemary Woodhouse. The two rent an apartment in downtown New York, and while he dedicates himself to acting, she takes care of the house. Soon, the couple will be approached by two eccentric yet pleasant elderly people, Roman and Minnie Castevet, their neighbors. A friendship will begin that is much appreciated by Guy, who is drawn to Roman's oratorical charm, but somewhat uncomfortable for Rosemary, who will gradually feel increasingly uneasy about Minnie's attentions. News will break the quiet routine of the Woodhouses: Rosemary is pregnant. The conception occurs while she lies unconscious, thus beginning a crescendo of disturbing events that will mature Rosemary's awareness of living next to a couple dedicated to witchcraft and the cult of Satan. From then on, her desperate struggle to snatch the unborn child from the clutches of those people will begin.

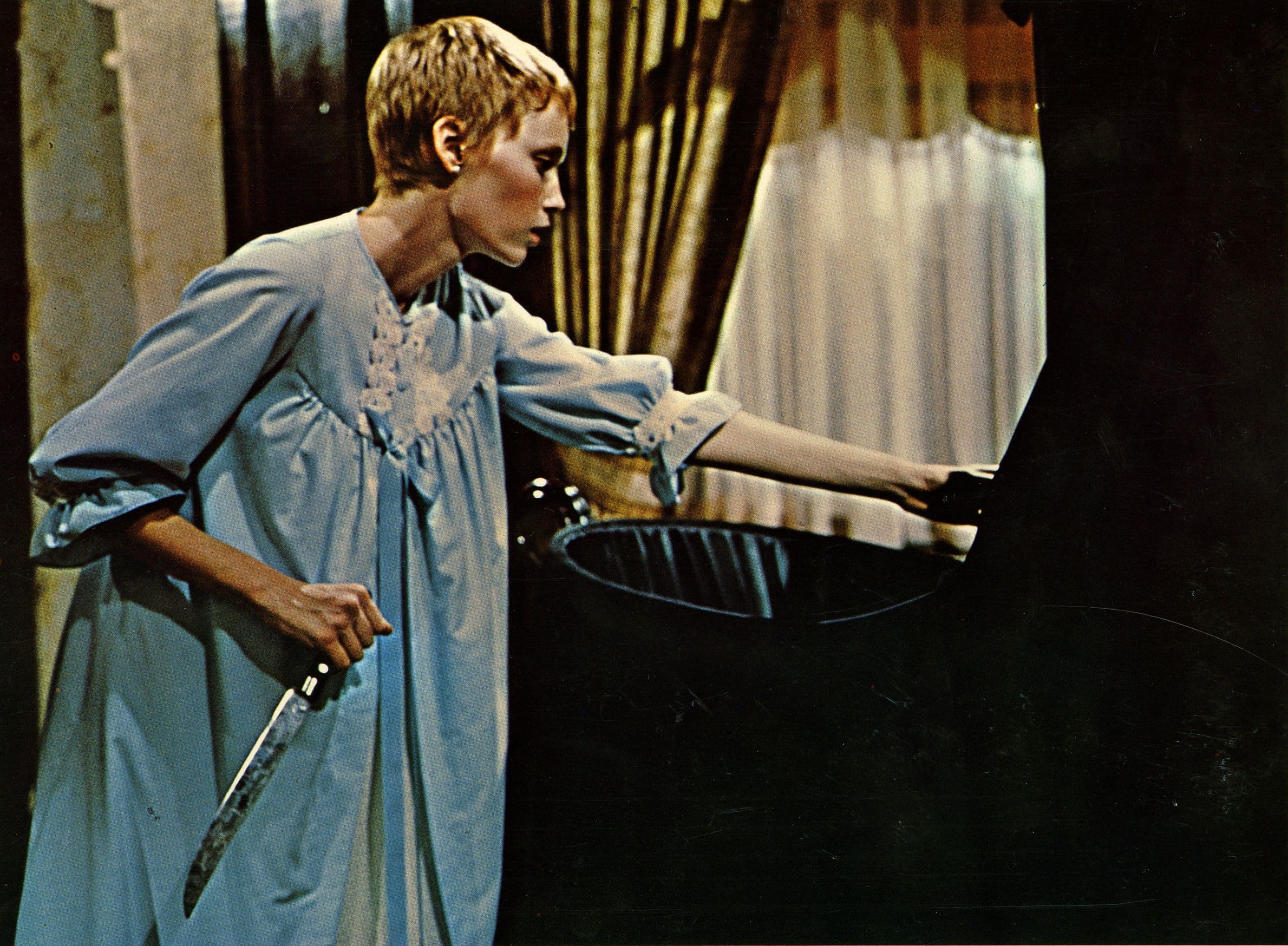

There are several scenes that have acquired immortality and fame over time. For example, the one where Rosemary breaks down the title of a book to try and anagram it, using Scrabble tiles: the camera follows her attempts and seems almost to participate in her speculative effort. Another famous scene is when Rosemary runs through the infernal New York traffic, nine months pregnant. All the cars stop almost miraculously as she passes: even more incredible to think that this scene, at Farrow's own suggestion, was shot improvisationally, without any arrangements with the drivers present. Polanski calmly told her: "Don't worry, Mia, no one would run over a pregnant woman!" And indeed, that was the case. Another striking iconic scene of the film is the final one where Rosemary bursts into the Castevets' apartment wielding a kitchen knife: the camera follows her from behind, stealthily, almost with mute deference, as the girl advances with uncertain steps towards the heart of the abomination. The final scene of Rosemary’s Baby is a miracle of balance: on one side, Rosemary, wielding a knife, gazes into the abyss, uncovering its terrifying recesses; on the other, the conclave of Satanists, gathered in adoration of the child, who welcome the mother in a silence imbued with indecision and fear for the child's fate. The coexistence of these two forces – tension and acquiescence – generates a kind of emotional leveling at the outset. Then Rosemary approaches the terrible cradle and draws aside its curtain. Rosemary's horror at the sight of the newborn is humanity's horror in the face of the Supernatural, the Unspeakable. When Roman presses her, telling her that the child has its father's eyes, an inarticulate, devastating despair opens up for Rosemary. Polanski emphasizes the psychological perception of reality by not showing the child to the viewer, but rather showing Rosemary's terrified face. Rosemary's question: "What have you done to him?" violently highlights the theme of perception, dissolving the plane of reality from Guy's eyes to Satan's yellow eyes, above her during the rape scene. It is a kind of transfer that, from the black taffeta of the cradle, invades the mother, finally making her conscious of everything. And there is no greater horror for her.

The work presents several layers into which one can delve, but two of them can be identified as a dual interpretative key to unlock its semantics. First, one perceives the theme of metropolitan alienation and how this alienation translates into mystery and hidden anguish within the walls of one's home. A gradual loss of all points of reference precisely in the place par excellence that should protect and welcome us. Rosemary's face, in this sense, initially disenchanted and cheerful, then pale and emaciated, is the most pregnant metaphor to delineate this deaf anguish, this creeping fear that gradually makes its way. Then, naturally, there is the esoteric theme: initially it gleams between the lines, then it strengthens, creating a climate of constant tension in the viewer, who is informed of the rituals, the interpreters, the magical objects, and the dark powers. The theme of the supernatural is introduced into the scene, with great semiotic intuition on Polanski's part, through the power of images, which gradually become more potent, more explicit, more loaded with meaning. First there is that strange pendant that the two diabolical old people give to Rosemary, then the unsettling paintings in their apartment, then the book 'All of them witches' full of illustrations of witches and warlocks, which is sent to Rosemary to warn her against the two, and finally the cradle draped in black where the baby rests, with the inverted cross hanging. In this work, an iconographic power hovers, which somehow devours the logos and seduces it to its will. A spell woven through images that is almost impossible to rationalize, as often happens upon waking when we find ourselves desperately trying to fix in our minds a terrible image full of arcane meaning that flashed in a dream, but which somehow escapes us like vapor through our hands.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...