Scarface

1983

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Directed by an inspired Brian De Palma and written by Oliver Stone, Scarface stands as perhaps one of the best remakes ever: the film is in fact based on Howard Hawks' 1932 Scarface, starring a superb Paul Muni as Tony Camonte. But to define De Palma's work as a mere "remake" would be reductive; it is rather a seismic reinterpretation, a bold reimagining that isn't limited to a temporal update, but rather a profound cultural and thematic reworking of the gangster archetype, transforming it from the Prohibition-era bootlegger to the epic drug lord of the neon-drenched eighties.

Here, instead of the roaring 1920s Chicago of Hawks' film, shrouded in the mists of Prohibition and the shadow of Italian-American feuds, there is the sun-drenched Miami of the 1980s. A decade not coincidentally dubbed "The Decade of Greed," where Tony Montana's arrival in 1980 is situated within a precise and turbulent historical context: that of the Mariel exodus. Castro's law, which emptied Cuban prisons, unleashed a tidal wave of exiles onto Florida's shores, among them numerous criminals and outcasts, not exactly willing to do menial work to make ends meet. Miami, from a placid tourist destination, quickly became the epicenter of a new, brutal cocaine Eldorado, a city that De Palma's work depicts with chromatic saturation and neon lights, almost as if it were a character in itself, vibrant and corrupt, seductive and lethal.

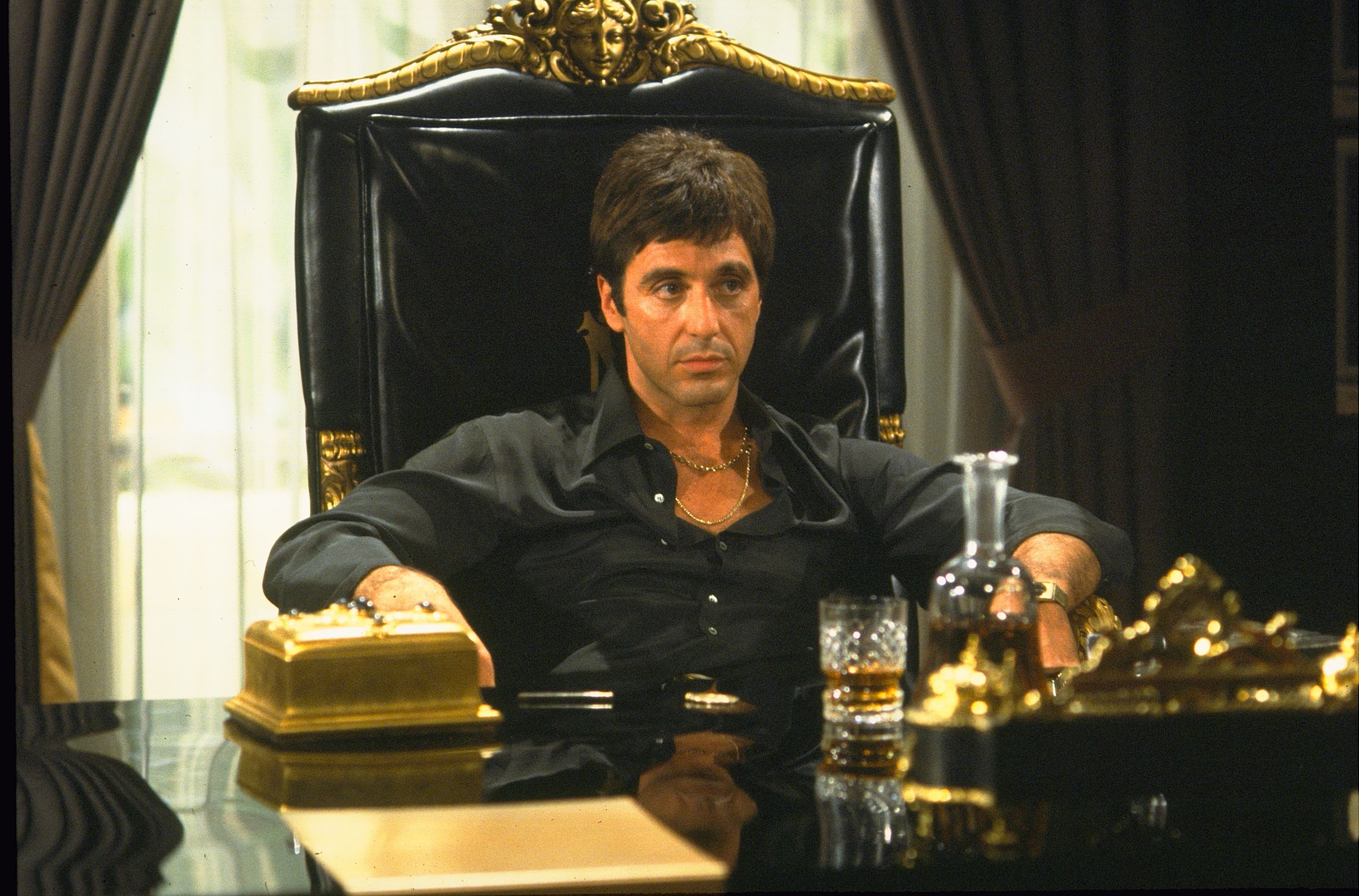

The ascent of one of these exiles, Tony Montana, to the heights of crime is also a young Al Pacino's initiatory journey through the dark labyrinths of perdition. A journey, it must be said, that Pacino undertakes with a fervor and intensity almost akin to method acting, chiseling an iconic performance that oscillates between an animalistic roar and the lament of paranoia, making Tony an anti-hero both magnetic and repulsive. He is not just a gangster climbing the pyramid; he is a man whose immoderate ambitions are inversely proportional to his capacity for self-control and discernment, destined to implode under the weight of his own hubris.

Tony begins his career by stealing a drug shipment from Colombian traffickers in a truly memorable scene: locked in the bathroom, he is forced to witness the dismemberment of a comrade with a chainsaw. That sequence, brutal and almost unbearable for its raw realism, is not gratuitous: it is a baptism by fire, a rite of passage that De Palma calibrates with surgical precision to immerse the viewer in the raw reality of uncompromising violence. His liberation and the ensuing relentless revenge are a programmatic declaration. This first criminal act already provides the film's aesthetic signature and Tony's criminal dimension: a ruthless man determined to pursue his goals, but also an individual whose moral code, albeit distorted and primitive, adheres to an internal logic of loyalty – or revenge for betrayal – that distinguishes him from Sosa's cold calculating nature.

Brian De Palma gives us other unforgettable scenes, culminating in the final shootout where Tony fights like a lion, haranguing the assassins who have entered his home to kill him and wielding a submachine gun with hoplitic power. This sequence is not just an explosion of violence, but an almost Wagnerian orchestration of destruction, an operatic culmination where Tony's megalomania clashes with his inevitable downfall. The luxurious villa transforms into a besieged fortress, a golden mausoleum for its mad king. But De Palma's art does not exhaust itself in the representation of excess; it resides in his ability to orchestrate the criminal melodrama with a baroque aesthetic, composed of hypnotic tracking shots, virtuosic framing – consider the use of the split diopter – and a chromatic saturation that exalts the corruption of the American dream.

Meticulous attention to the protagonist's psychological genesis makes this work unique: a kind of handbook on the corruption of emotions and human deviation in a broader sense. Scarface is, at its core, a Shakespearean drama transplanted into the kitsch opulence of the 1980s, where Tony Montana's unbridled ambition clashes with his irremediable hubris. There is no redemption for him, only the inevitable downfall that follows the excess of power and the loss of every glimmer of humanity and affection, even towards his sister Gina or his trusted Manny. To this, add the sharp pen of Oliver Stone, who chisels cutting dialogues, steeped in vulgarity and disillusionment, painting a raw and unfiltered fresco of the soft underbelly of the American dream, a dream that for Tony proves to be a self-destructive chimera. The protagonist's journey into the world of crime is also his dark voyage towards the moral devastation of his own self, a personal descent into hell that transforms him from an ambitious immigrant into a paranoid and isolated tyrant, imprisoned by his own wealth. Scarface is more than a gangster film: it is a work that, despite its initially controversial reception, has transcended the genre to become a cultural icon, a warning about the emptiness of success founded on violence and obsession, and a timeless masterpiece about the fall of an anti-hero who wanted the world, but in the end achieved only a solitary and thunderous death.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...