Charade

1963

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Stanley Donen's Charade is, in all likelihood, the best Alfred Hitchcock film that Alfred Hitchcock never made. This is not a criticism, but the highest of compliments. Stanley Donen's work is such a perfect, witty, and elegantly constructed homage to the romantic thriller formula of the Master of Suspense that it has become a masterpiece in its own right. It is an impeccable cinematic cocktail, a perfectly measured blend of suspense, sophisticated comedy, and glamour, shaken and served with a lightness and verve that only a director with the rhythm of a musical in his veins could conceive. A film of almost mathematical perfection in the pure, indescribable pleasure it gives.

Charade is very similar to Hitchcock's more mainstream works, as it lacks the dark emotional currents and psychological obsessions that often permeate the director's more serious works. The most immediate and accurate comparison is with the mix of suspense, romance, and comedy found in films such as To Catch a Thief and, above all, North by Northwest. As in the latter, we have the protagonist thrown into a conspiracy he does not understand, a parade of ambiguous characters, a script that is a clockwork mechanism of twists and turns, and a glamorous setting that provides the backdrop for the action. But where Hitchcock always tinges his stories with a touch of anxiety, paranoia, and almost Catholic guilt, Stanley Donen orchestrates it all with a different baton. His is the sensibility of a master of musicals, the director of masterpieces such as Singin' in the Rain. Donen directs Charade as if it were a musical without songs: the dialogue has a sparkling, percussive rhythm, the action scenes have an almost choreographic grace, and the love story has the lightness of a pas de deux. He replaces Hitchcock's angst with pure, infectious effervescence.

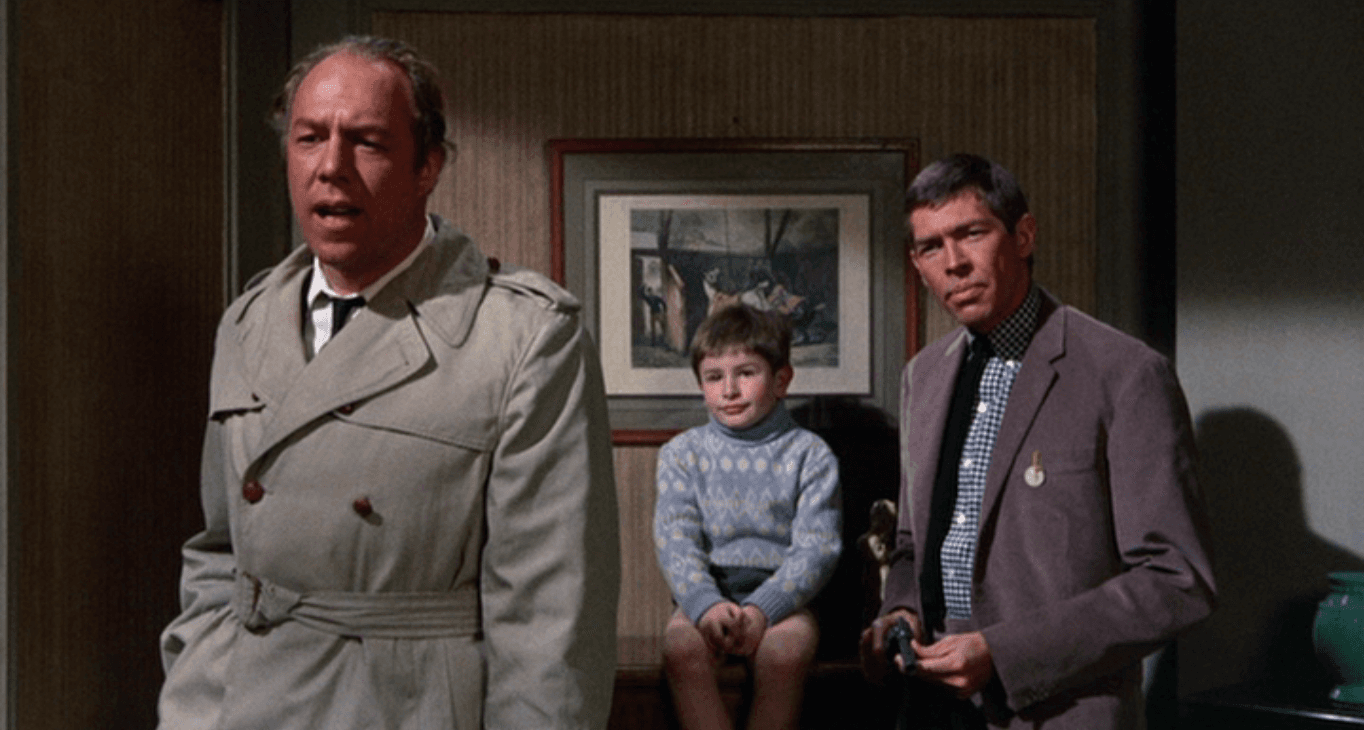

Much of the credit goes to Peter Stone's screenplay, a diabolically clever device. Stone, here in his first major work, creates a thriller that constantly plays with the viewer's expectations. The plot is a wonderful pretext: Regina Lampert, a witty and impeccable simultaneous interpreter, returns to Paris from a vacation with the intention of getting a divorce, only to discover that her husband has been murdered and their apartment has been completely ransacked. She soon finds herself hunted by a trio of her late husband's former comrades, all convinced that she knows where a quarter of a million dollars in gold stolen during the war is hidden. Her only supposed ally is a charming and mysterious man, Peter Joshua, who keeps changing his name and his version of events, leaving Regina (and us with her) in a perpetual state of doubt: is he her savior or the most skilled of her persecutors?

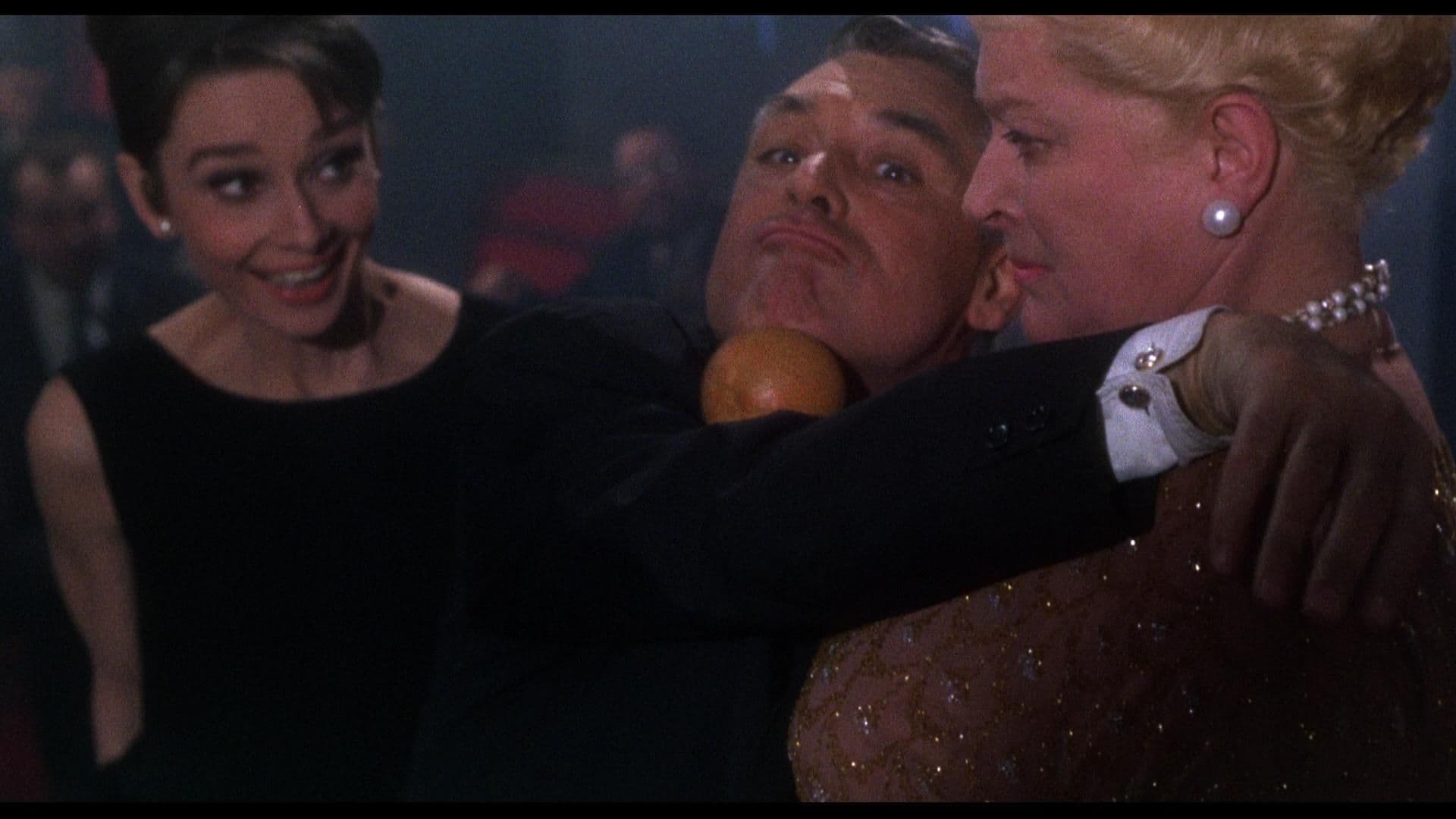

The greatness of the screenplay lies in this game of multiple identities, a continuous charade that makes every scene a delightful minefield of lies and half-truths. And then, of course, there are them: Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn, one of the most charismatic and perfectly matched couples in film history. Their chemistry is legendary.

Audrey Hepburn does not play the classic damsel in distress. Her Queen Lampert is a modern, intelligent, independent woman with an irresistible dark sense of humor. Even in the face of death, she never loses her composure and wit. Her wardrobe, curated by her trusted stylist Givenchy, is a lesson in style that defined the elegance of the early 1960s. Cary Grant, on the other hand, masterfully plays with his own icon. At the time, he was almost 60 and concerned about the obvious age difference with Hepburn. Stone's script brilliantly solves the problem by making Regina the romantic driving force of the relationship. She is the one who pursues him, who flirts shamelessly, who provokes him. This reversal of roles not only downplays the age difference, but makes their dynamic incredibly fresh and modern. Grant is at the height of his mature charm, a man who could be a hero, a rogue, or both, and whose enigmatic smile is the key to the entire film.

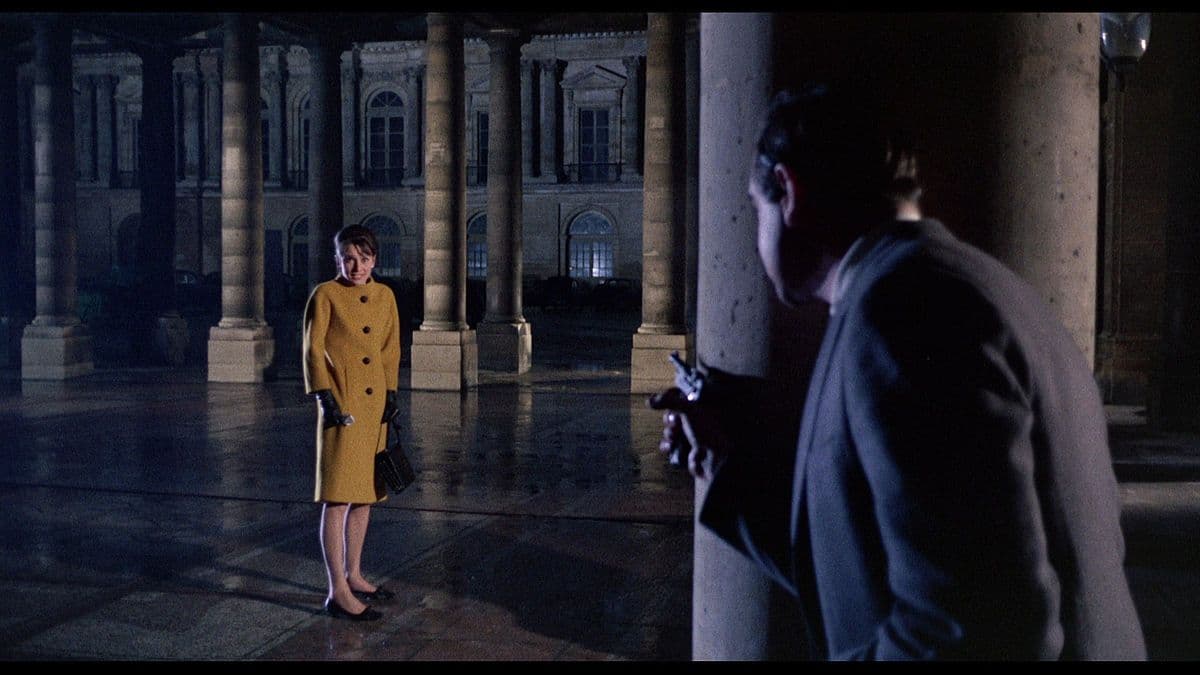

Set in its cultural context, Charade can be seen as the last, sparkling toast to the Camelot era. Released in late 1963, it captures an atmosphere of optimism, glamour, and sophistication that would soon be swept away by darker historical events. But there is another, more oblique and nerdy analogy that can be made. Despite being a Hollywood production through and through, the film, with its Parisian setting and playful, self-aware spirit, seems to engage in a distant dialogue with the French Nouvelle Vague. The way it deconstructs and reconstructs thriller tropes, its dialogue that seems to wink at the viewer, and its real-life locations on the streets of Paris have a lightness and modernity that would not be out of place in a Truffaut film, if Truffaut had had an unlimited budget and the two biggest stars on the planet at his disposal.

Ultimately, Charade is entertainment perfection. It is a film that does not have an ounce of fat, a single out-of-place scene, or a wasted line. Donen's direction is a miracle of balance, the screenplay a gem of narrative engineering, and its protagonists are simply divine. A work that represents the absolute pinnacle of a certain type of cinema: one that believes that intelligence, style, and pure pleasure can and should go hand in hand. It's an hour and fifty minutes of pure, uninterrupted delight.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...