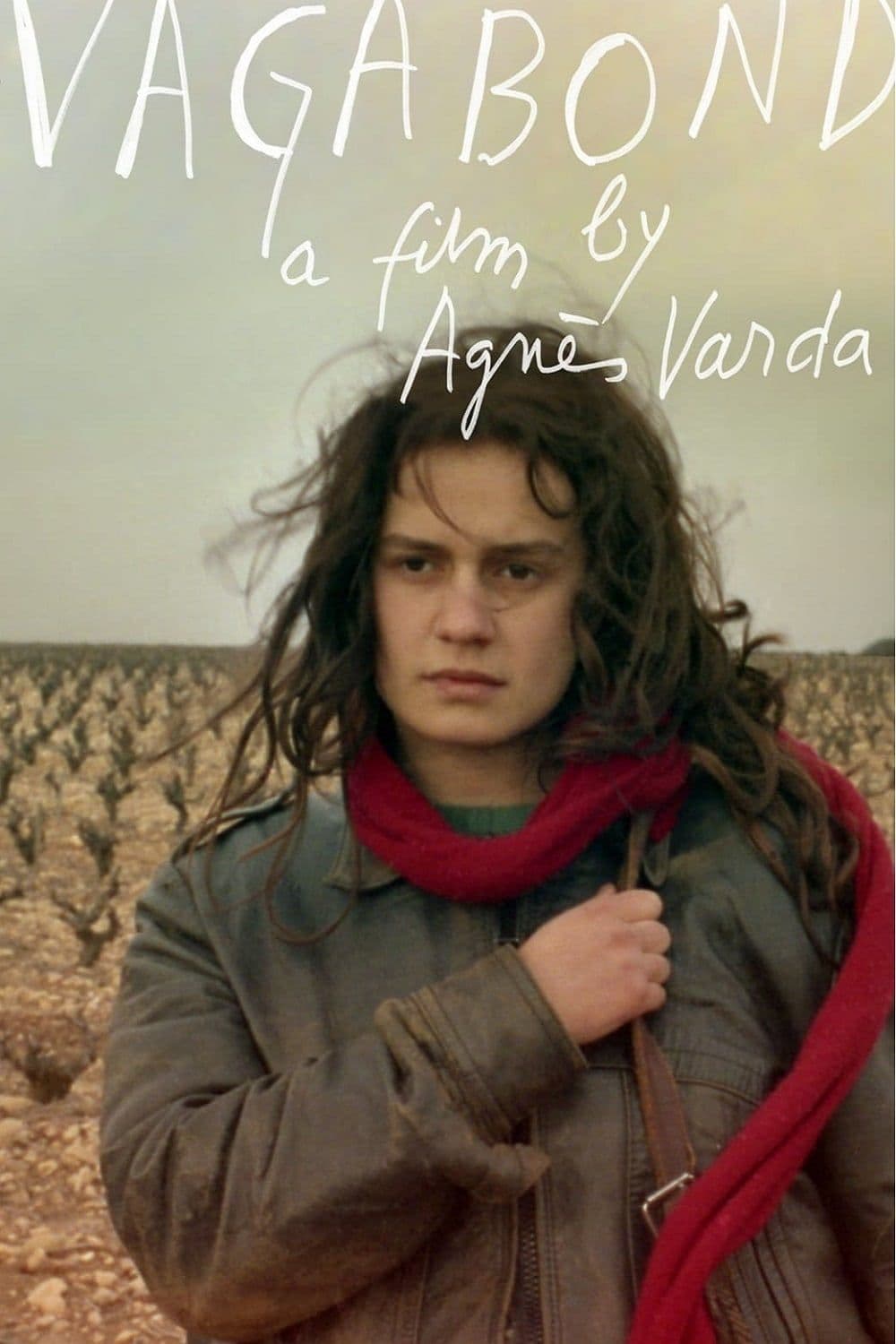

Vagabond

1985

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A splendid film, winner of the Golden Lion in Venice, by a great director, Agnès Varda, too often forgotten. One of the most singular and courageous voices in French cinema, Varda – co-founder and prominent figure of the Rive Gauche, a current parallel to and perhaps even more intellectually daring than the Nouvelle Vague – always forged her own path, creating a visual language she herself termed "cinécriture": an art of writing with images, imbued with an almost anthropological curiosity for humanity and its relationship with the environment. This Golden Lion, awarded in 1985, was not just a belated recognition for a career already rich in significant works, but the affirmation of a frontier cinema, capable of investigating the cracks in society and the soul with disarming honesty.

The film focuses on the unbridled life of a young woman, Mona Bergeron, starting with its tragic epilogue: the discovery of the poor girl's body, dead from cold and hardship in the middle of a field. An emblematic image, almost pictorial in its desolation, which immediately imprints a tone of irredeemable fatality. This narrative device, which reverses traditional chronology, transforms the story into a kind of posthumous inquiry, a puzzle of fragments and testimonies that try, without ever fully succeeding, to reconstruct the physiognomy of an existence.

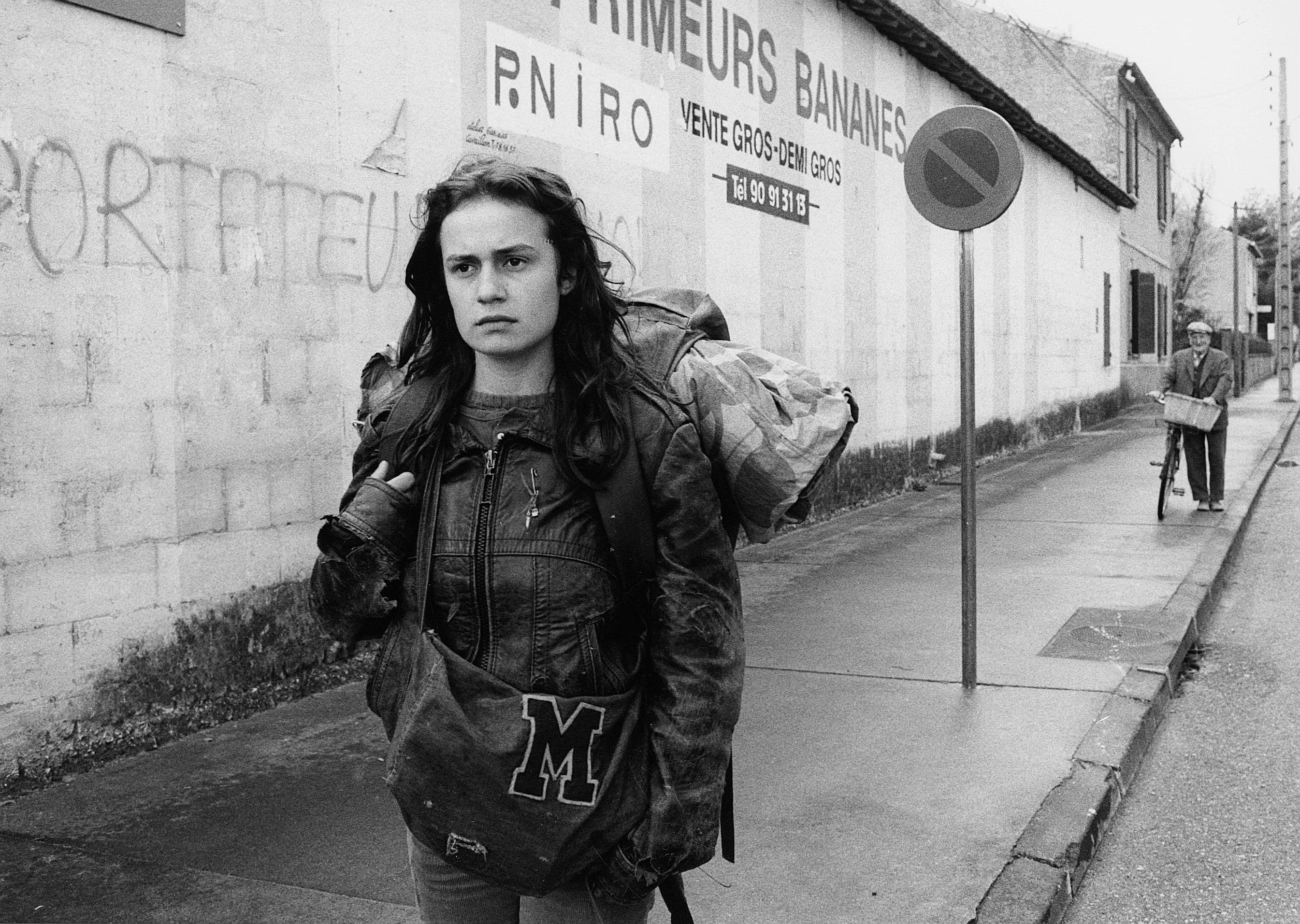

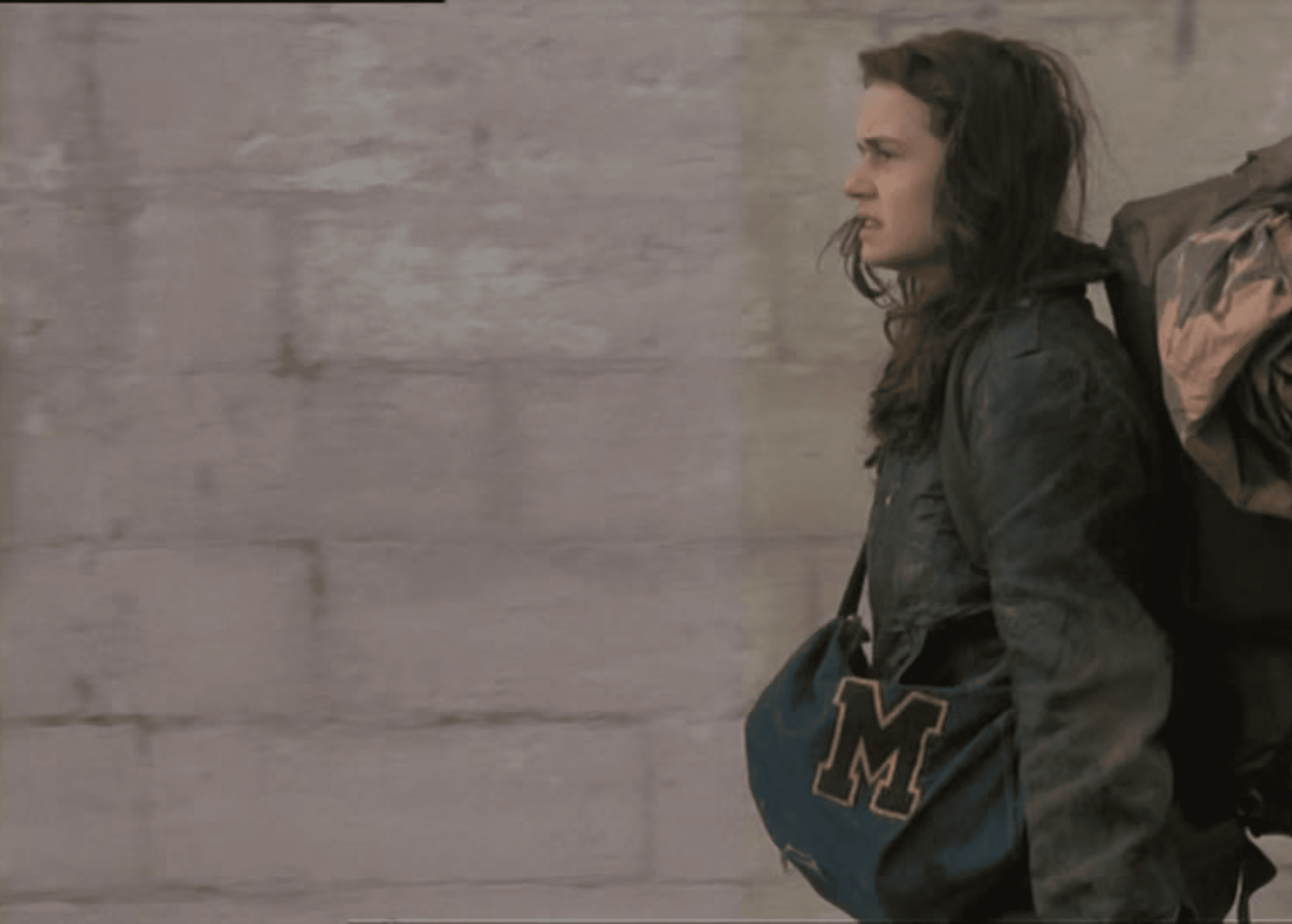

Her life is retraced through flashbacks, following her wanderings. However, it is not a simple physical journey, but an existential odyssey, a radical nomadism that is at once a choice of freedom and a condemnation to isolation. Varda adopts an almost documentary structure here, interviewing the various characters Mona encountered along her path, from farm laborers to university professors, from elderly peasants to wandering philosophers. Each testimony adds a piece, but far from defining Mona, it accentuates her mystery, revealing more about the projections and prejudices of those observing her than the girl's true essence.

We see her fighting against people's distrust due to her wandering way of life, struggling to make do by taking on the most humble jobs, living on little, always adrift, always on the fringes of a society that never appears hostile but rather different, alien, unknowable. This is one of the film's most astute interpretations: society is not depicted as an oppressive monster, but as a fundamentally indifferent entity, or rather, incapable of accommodating what does not fit into its preconceived categories. The people Mona encounters do not reject her out of malice, but out of a deep-seated misunderstanding, out of discomfort in the face of an existence that challenges every bourgeois logic of security, belonging, and productivity. Mona is the rogue splinter that cracks the reassuring surface of normality, forcing those who encounter her to confront their own limitations and fears.

Fundamentally, the people she meets, not understanding her lifestyle, struggle to find an identity for her. It is a reflection of our own inability to assign a role or meaning to those who do not conform to social expectations. Mona has no past to redeem nor a future to build according to conventions; her existence is pure present, a succession of moments lived with a fierce and self-destructive freedom. It is in this refusal of every label, every bond, every "story," that her strength and, at the same time, her extreme vulnerability lie. Varda seems to suggest that, in a world obsessed with definitions and belonging, true freedom can only be perceived as alienation, and that the price of absolute autonomy is definitive exclusion.

Mona is as if she were a ghost passing through their lives, leaving a sense of bewilderment mixed with repugnance. The metaphor of the ghost is very powerful: Mona leaves no traces, clings to nothing; she is pure energy in motion, a fleeting shadow that evokes the precariousness of existence itself. The "repugnance" is not so much for her dirtiness or her homelessness, as for the terror her life choice evokes: the loss of all protection, all security, the fall into the void of the unknown. It is the fear of what cannot be controlled, of what cannot be tamed, the fear of the radical solitude that every human being, deep down, carries within themselves. This film, therefore, is less a social drama than a philosophical inquiry into the nature of freedom and resistance.

Varda is always interested in a psychological rather than narrative aspect in her films, and in this one too, which is in fact her masterpiece, she strips bare Mona Bergeron's emotions, her wandering soul, with tenacious purity, with candid determination. Varda does not judge, does not moralize; she merely shows, with a gaze that combines cold documentary objectivity and a profound poetic empathy. Her approach is almost Bressonian in its essentiality, but with a unique human warmth and aesthetic curiosity. The film is imbued with a raw introspection, which does not rely on explanatory dialogues or textbook psychologisms, but on the power of images, silences, minimal gestures. Mona's "purity" lies in her authenticity, in her total adherence to her deepest self, even at the cost of self-annihilation. Her "determination" is not directed towards a goal, but towards maintaining a state, a non-belonging, a perpetual "being against." For Varda, Mona is a symbol of human resistance, a tragic beacon that illuminates the rigidities of a system that only contemplates deviance as pathology.

A great interpretive performance by Sandrine Bonnaire, who imbues the film with a passionate and lyrical quality that makes it a bitter and crepuscular work. Bonnaire, very young at the time, embodies Mona with magnetic force and surprising maturity. Her face, often dirty and marked, is a mirror of deep fatigue, but also of indomitable resilience. Her silences are more eloquent than a thousand words, her gazes betray a tormented yet unyielding soul. It is an interpretation of subtraction, of a body that speaks more than the voice, of a stage presence that absorbs and reflects the harsh surrounding reality. The film's lyricism emerges from its ability to find beauty and dignity in desolation, in the incessant struggle against the elements and human indifference. The stark and windy winter landscape, natural lighting, and cold, almost monochromatic cinematography contribute to creating this crepuscular atmosphere, a visual symphony that accompanies Mona's ineluctable decline, transforming her end not only into a personal tragedy but into a disquieting reflection on freedom, solitude, and the fate of the individual in a society that, whether it wants to or not, does not tolerate its ghosts.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...