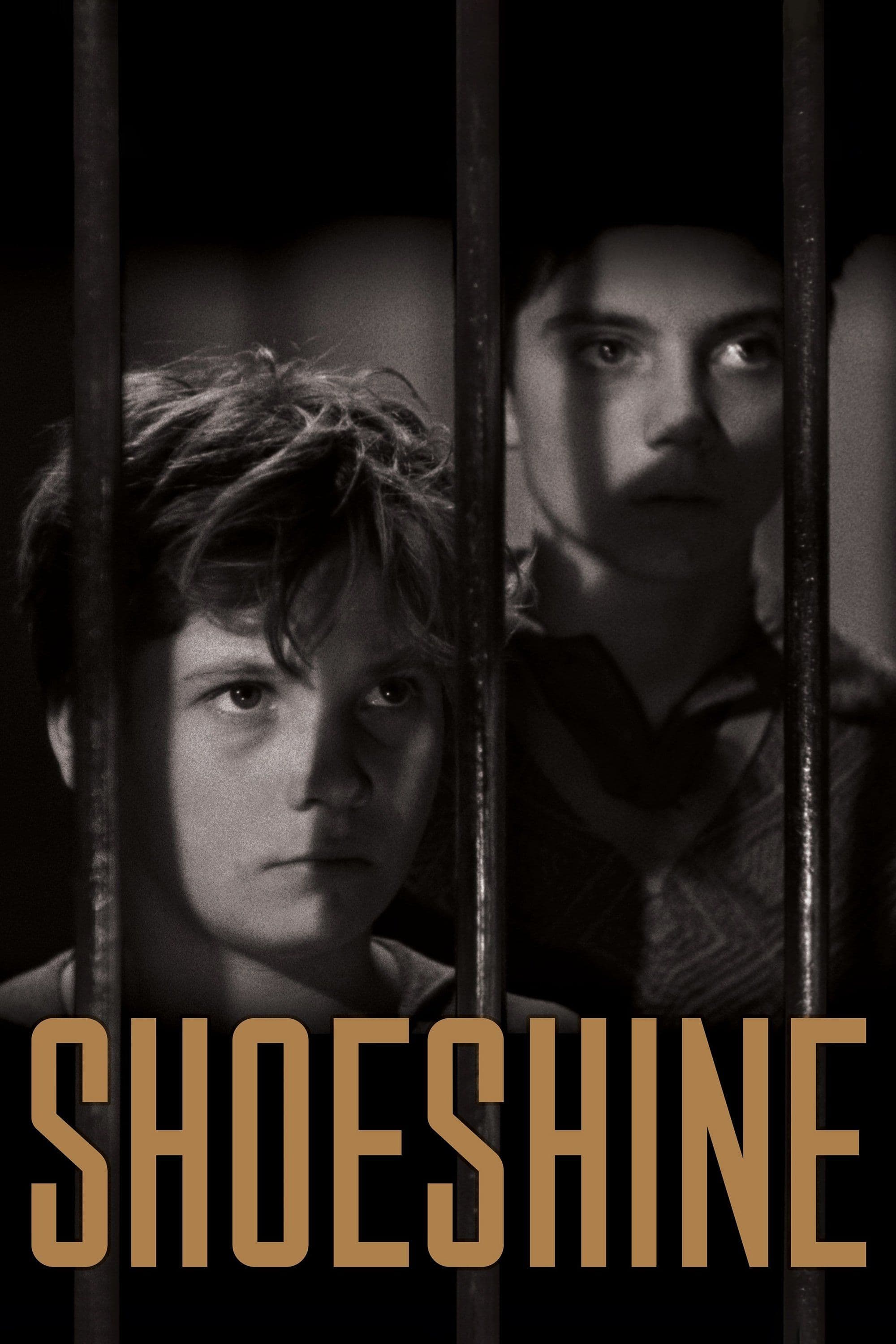

Shoeshine

1946

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

De Sica, a year after Rome Open City, which shaped neorealism, internalizes Rossellini's lesson and creates a splendid work, torn between a love for the common people and raw narration. The Rossellinian lesson, understood as a moral and stylistic imperative to adhere to post-war reality, is here internalized and sublimated by De Sica through a suffering, almost Leopardian humanity that permeates every shot. Where Rossellini perhaps preferred an almost documentary-like recording, a detached yet compassionate eye, De Sica adds a vein of profound emotion, an empathetic embrace towards the downtrodden, which translates into an even more harrowing and deeply felt narration. It is not simply a chronicle, but an elegy of childlike suffering.

The new cinematic movement sought to free itself from all the stylistic embellishments that had characterized the Fascist era, to narrate raw and unvarnished reality, without pretense or artifice (one thinks of the Baroque excesses of neoclassicism and all the legacy of artificial reality they brought with them). This liberation was not only aesthetic but ethical. It was about dismantling the rhetorical and falsely optimistic edifice of the twenty-year period, the so-called "white telephone cinema" with its escapist bourgeois comedies and artificial dramas, to confront the ruins – physical and moral – left by the war. Neorealism, with its predilection for outdoor shooting, non-professional actors, and often raw, almost documentary-like cinematography, was not merely a stylistic choice, but a declaration of intent: cinema had to become a witness, a critical conscience for a nation on its knees, yet not devoid of dignity.

Neorealist stories are born from, live within, and exhaust themselves in the common people. In Shoeshine, this "people" is embodied by the most vulnerable and innocent figure: the child. Giuseppe and Pasquale, the two young shoeblack boys, are a living metaphor for a wounded Italy, a lost generation, forced to grow up too quickly amidst the ruins of an adult world that betrayed it. They are not heroes, but survivors, whose precarious existences become a silent cry against the injustice and poverty that ravaged post-war Rome. Their story is not an isolated case, but the emblem of thousands of similar fates, a suffering collective that Neorealist cinema aimed to reveal and, in some way, redeem.

Two young Neapolitan shoeblack boys (or sciuscià, a contraction of the English 'shoe shine') decide to embark on a shady deal, with the consequent result of ending up in prison. That "shady deal" is merely a desperate and naive attempt to scrape together the little money needed to fulfill a childhood dream: to buy a horse, a symbol of freedom, strength, and innocence, an almost messianic aspiration in that context of desolation. Their downfall is not due to malice, but to a fatal concatenation of naiveté, adverse circumstances, and a distorted justice, blind to their age and desperation. It is an indictment of the prison system, an institution that, instead of rehabilitating, destroys the soul, transforming hope into resentment, innocence into irreparable trauma.

A cathartic journey will begin for them, stripping them of their childhood and abruptly throwing them into the adult world. But this is not a liberating catharsis, but rather a descent into hell, an annihilating loss of childhood. The walls of the reformatory become the stage for a psychological drama of rare intensity, where the sacred friendship between Giuseppe and Pasquale is methodically eroded, victim of a punitive system that exploits their weaknesses and loyalty to pit them against each other. Hunger, cold, the violence suffered from other inmates, and the incomprehension of adults corrode the fraternal bond, transforming love into suspicion, support into hostility. It is a process of disintegration that leads to the inevitable final tragedy, an epilogue of Shakespearean intensity, where the accidental death of one becomes the seal of the other's definitive condemnation, a harrowing image that imprints the brutality of reality upon the heart. They are no longer just shoeblacks, but trampled souls, symbols of an entire generation lost in the post-war chaos.

Particular emphasis is placed on Cesare Zavattini's excellent screenplay and De Sica's meticulous work with the camera. Zavattini's contribution is fundamental; his theory of the "close observation of reality," of attention to the most mundane everyday life to reveal its extraordinary human complexity, finds one of its supreme expressions in Shoeshine. The screenplay avoids all rhetoric, all melodramatic excess, to focus on the truth of small gestures, silent expressions, lost gazes. De Sica, for his part, proves to be a sublime conductor, capable of directing a cast of non-professionals, particularly the two very young protagonists Rinaldo Smordoni and Franco Interlenghi, with an almost surgical sensitivity and precision. His direction is never invasive, but always present, with shots that enhance the desolation of the settings, the rawness of emotions, the silent power of faces. Anchise Brizzi's cinematography, with its contrasted black and white, not only captures the misery of the post-war period but sculpts dignity and suffering onto the children's faces, making every frame an unforgettable visual testimony.

A work that made our cinema shine and of which we are proud. Shoeshine was not only a critical and public success upon its release, but it earned Italy the first, historic, Special Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, long before the category was formally established. This international honor consecrated Italian Neorealism as a leading movement, a stylistic and moral beacon for world cinema. Its influence would extend far beyond Italian borders, inspiring generations of filmmakers, from the French New Wave to British Free Cinema, and even touching emerging cinematographies of the Third World. Even today, its emotional power and relentless honesty make it a timeless masterpiece, a universal warning about the fragility of innocence and the brutality of social injustices, a work that continues to speak to the heart and conscience of anyone who approaches it.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...